In August 2019, I spent an hilarious and fascinating afternoon with Christopher Maynard, writer of the classic 1977 book Mysteries of the Unknown: Ghosts, reissued by Usborne Publishing in October this year. It became a feature entitled “Where Ghosts Gather” in issue 385 of the Fortean Times, dated November 2019. The full article is now here…

WHERE GHOSTS GATHER

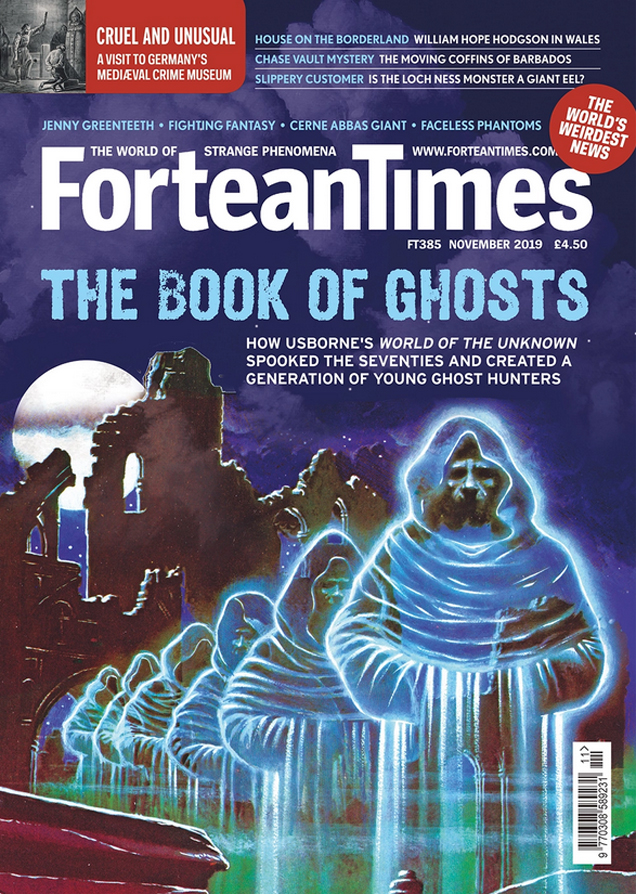

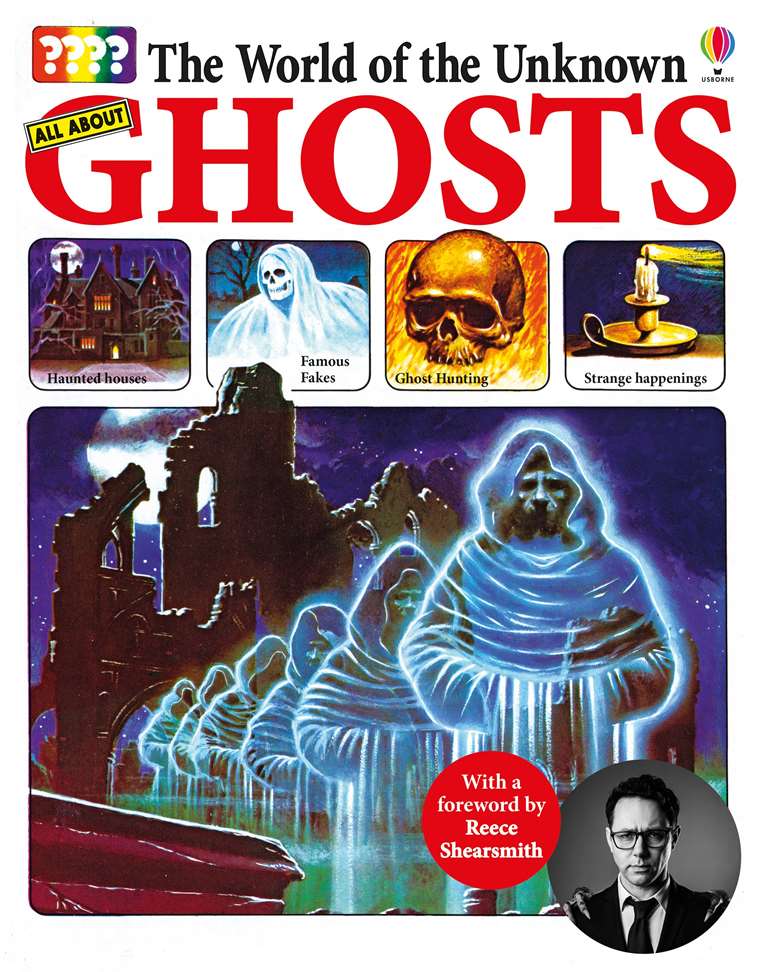

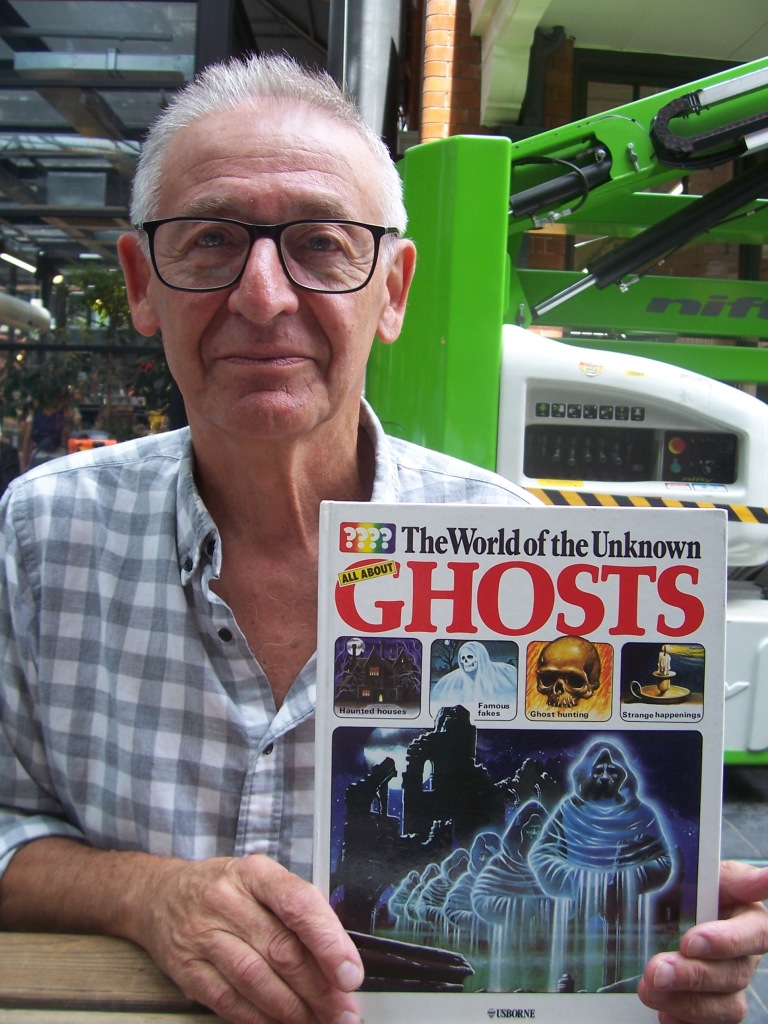

In 1977, Usborne published World of the Unknown: Ghosts, the children’s book that inspired a generation of junior Forteans. Four decades on, following a concerted fan campaign, the book is back in print… and the perpetually haunted Bob Fischer tracked down its pleasantly surprised writer, Christopher Maynard.

The man responsible for some of my more potent childhood nightmares is sitting opposite me at a picnic table in Old Spitalfields Market, basking in the syrupy East London sunshine of a late summers afternoon and – quite frankly – he’s at it again.

“There was an animal called the Behinder,” says Chris Maynard, in the mellifluous Montreal accent that has lost none of its delicious resonance since he left his native Canada for post-swinging London in the early 1970s. “You can tell when you’re being followed by a Behinder, because the hairs on the back of your neck prickle, and stand up. And the way to check that you’re being followed by a Behinder… when that happens, whip around really fast. If there’s nothing there, but you’ve still got that feeling, you know you’re being followed…”

Good grief, Chris. What do they look like?

“You can feel them, sense them, almost taste the fear they engender, but see them? Never! I’ve heard tell that you would drop dead if you ever saw one face to face. Though I take that with a pinch of salt…”

Forty years on, the architect of my 1970s night terrors is proving to be brilliant, engaging, and very funny company.

In 1977, Chris poured this fascination with the ghost stories of his Canadian childhood – told in hushed tones around the crackling fires of woodland summer camps – into a book that became a ubiquitous, and thrilling, mainstay of every British school library for years to follow. Ghosts was one of the earliest successes of the nascent Usborne Publishing house, one third of a trio of books issued under the umbrella title The World of the Unknown… the others being, inevitably, Monsters and UFOs. Its 32 pages are packed with tales of ancient hauntings, outlandish folklore and indispensable practical advice for primary school-age children with a healthy curiosity about what lies beyond the veil. Lovingly and vividly illustrated, it strikes a perfect balance between comic-book dynamism and factual reportage, all seemingly custom-designed to fire the imaginations of a generation of youngsters whose formative years had already been delightfully tainted by an upsurge of interest in all things supernatural. This, remember, was the decade of Rentaghost; of Hammer, Amicus and Tigon films; of Horror Top Trumps and Shiver and Shake comics.

“Peter Usborne, the owner of the company, would be sitting in the bath,” laughs Chris, “and he would think ‘Let’s do something on dinosaurs. Fossils and dinosaurs… and then we’ll do something on the Ice Age and we’ll bundle it up.’ And somewhere along the way, the idea of folklore came up… which is why Ghosts was bundled with Monsters, which was bundled with UFOs. He would have just come in and tossed it onto the pile, and the editorial teams would have picked it up and said ‘Yeah, we’ll take that one.’ And that was it, that was the brief.”

So was it something that Chris actually pitched to write?

“I really can’t remember! Most likely what happened was that somebody would have come in and said, ‘Chris, these are the books we’re thinking of doing over the next year, which ones do you fancy running with?’ And I’d say ‘Yeah, I’ll do the Ghosts one… that’ll be a lot more fun.’ It just struck me as something that I could have a shot at. It struck a funny bone.”

“UFOs,” he confides, bashfully, “are not my cup of tea…”

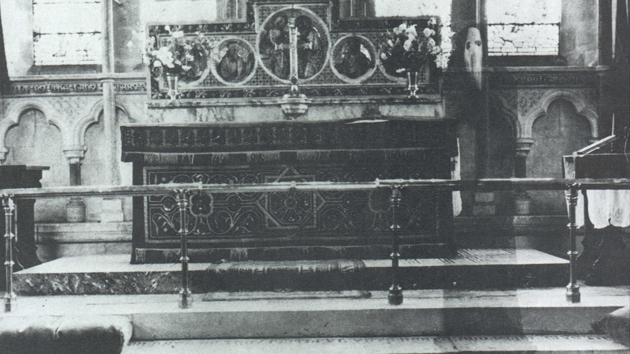

I was around seven years old when I first discovered the book, nestling in a shadowy corner of Levendale Primary School’s modest library, somewhere between Willard Price’s Safari Adventure, a well-thumbed haul of Target’s Doctor Who novelisations, and a dusty, shamefully-neglected collection of the Children’s Brittanica. I can still remember the head-freezing pall of terror that enveloped me upon my first glimpse of a randomly-opened page; the collection of “Mystery Photographs” that swam back and forth through my nightmares for months to follow. There was the glowing, spectral figure of a woman in a flowing, formal gown, descending the stairs of Raynham Hall in Norfolk, captured on camera in 1936. There was the grinning driver of a 1950s Hillman Minx, entirely oblivious to the spirit of his recently-deceased mother-in-law, sitting expectantly on the back seat behind him. And – most chilling of all – there was the translucent figure of a spectral monk beside an elaborate altar, “taken in the early 1960s by the vicar of a church in England.” The hollow eyes of this latter apparition, two ragged holes cut into a white death shroud, seemed to bore into the very fibres of my being. I was convinced that my inadvertent eye contact with this terrifying spirit had, effectively, alerted the agents of the paranormal to my existence, and that a parade of malevolent ghosts, spectres and poltergeists, headed up by the towering, black-robed monk himself, would be gliding silently up the stairs to claim me in my sleep that very evening. As Chris’ text solemnly declares: “All three of these pictures are considered by experts to be genuine.”

If the experts were convinced, then so was I.

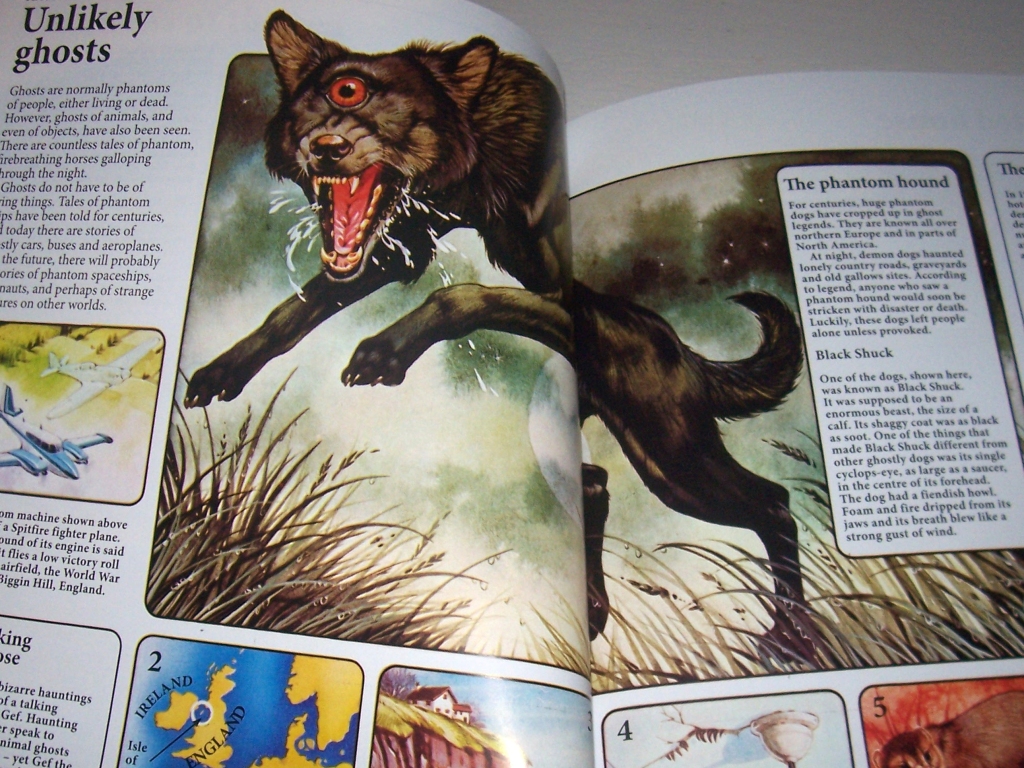

And yet this proto-panic attack inexplicably failed to deter me from investigating the rest of the book, and being somehow both terrified and intrigued by the stories within. I discovered “Tom Colley’s Ghost”, the spirit of the 19th century mob-leader, whose restless spirit was shackled to the rotting remains of his gibbeted body. In Tring. I winced at the fate of the phantoms of the Battle of Shiloh, grimly and ceaselessly re-enacting this brutal 1862 conflict of the American Civil War. I read wide-eyed about the Arabian “Afrit” ghost, whose rising could only be prevented by the driving of a fresh nail into the bloodstain of its associated murder victim; and of “Black Shuck”, the demon dog that haunted “lonely country roads, graveyards and old gallows sites”, distinguished by its “single cyclops-eye, as large as a saucer, in the centre of its forehead.”

And, obviously, I vowed never to set foot in “The Village With A Dozen Ghosts”: namely Pluckley, whose assorted spooks are vividly described beneath photographs of their respective haunts, all laid out on a detailed road map of this sleepy Kent idyll. Keen to hook up with the “White Lady of Dering”? Head for the burnt-out husk of Surrenden Dering manor, where she still glides silently through what remains of the library. From there, it’s a short walk to the Church of Saint Nicholas, where the 12th century “Red Lady” – “buried in a sumptuous gown with a red rose in her hands” – stalks the graveyard. Cross over Dicky Buss’s Lane to find “the hanging body of the schoolmaster”, a victim of suicide in the aftermath of World War I, whose phantom corpse, suspended from a laurel tree, “is said to be visible to this day, swinging in the breeze.” And then, on your way back to the railway station, pay your regards to “the ghost of the screaming man”, a brickworks employee “smothered to death when a wall of clay fell on him”, whose spirit still “screams in the same way as he did when he died.”

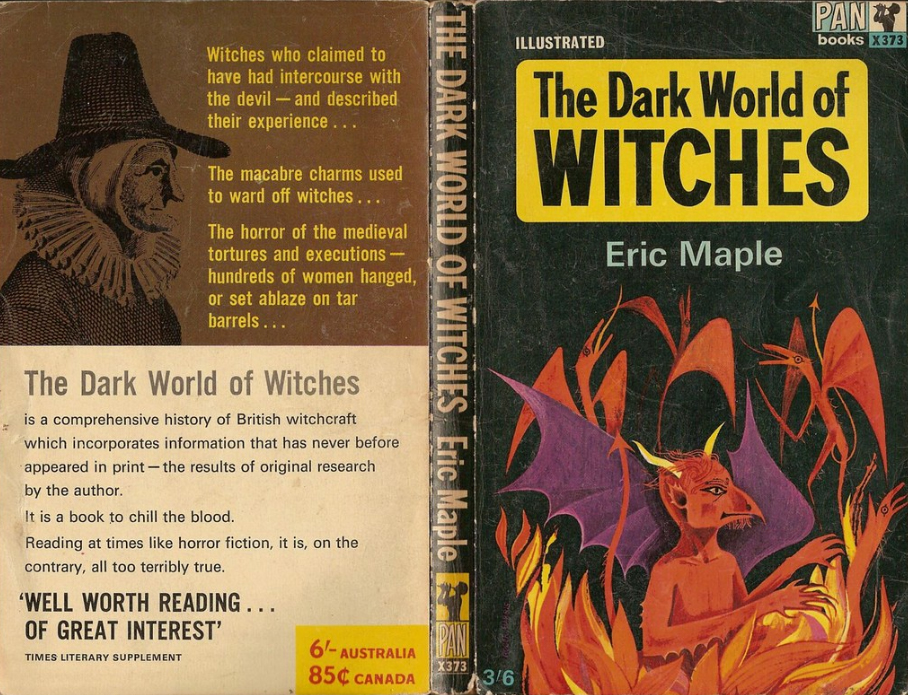

The book is an extraordinary feat of research, and I was intrigued to note that folklorist Eric Maple had been credited as “Special Consultant”. Maple, born in 1916 in Essex, was the son of a spiritualist medium and a voracious collector of folk and occult tales; his magnificently-titled works The Dark World of Witches, The Realm of Ghosts and The Domain of Devils forming a quintessentially 1960s triumvirate of books, published – entirely appropriately – by Pan.

“When I started doing research in libraries,” remembers Chris, “I realised that Eric Maple had a long pedigree. We tracked him down, and got in touch with him, and he’d been researching and writing folklore books for years. We wanted him as an advisor, as much to help me wade through this mountain of stuff that was out there. I was working through public libraries at the time, and he would have steered me towards newspaper libraries as well.”

The still-extant Society For Psychical Research is credited too, along with its one-time rival, the sadly defunct National Laboratory of Psychical Research. Chris has fond memories of making contact with a community of paranormal enthusiasts and societies that were arguably enjoying their heyday, in a 1970s Britain whose fascination with the otherworldly frequently crossed over into the mainstream media.

“They were these wonderful, eccentric little corners that we only discovered as we were working,” he smiles. “And they all had cuttings libraries – they’d been amassing folklore for years. And they would have regular symposia for people around the country… for all I know, people around the world. I never figured out the depth of all this. So they would be a real source of stuff that might not be in the broader public domain. That was really helpful, and Eric was particularly good at steering us to those kinds of places, and winkling out little bits and pieces.”

The double-page spread on Pluckley, however, was the result of an expedition made by Chris and Usborne art director David Jefferies, a day of bona fide ghost-hunting that makes him especially proud. “I like the fact that we did Pluckley,” he beams. “We went and did the research in the field. It was great, really delicious. [We had] the demented idea that we had to overlay it onto a map, so that was the one occasion when we actually took ourselves out and spent a day wandering around… and to my way of thinking at the time, it was a particularly successful page. This was important…” (We have a copy of the book on the table, open at the Pluckley double spread, and Chris is pointing proudly at one particular illustration.) “The compass! We wanted you to be able to orientate yourself, and made it a map where you could actually locate these various objects…”

But did any unsuspecting members of the Pluckley public not wonder why two strange men were wandering around their village all afternoon, taking photographs?

“I suspect,” laughs Chris, “if they had seen us, they would have thought we were estate agents! Or someone from the council. Why else would you be taking pictures of houses, and measuring up?”

Reading Ghosts as an adult, it’s clear that my seven-year-old self overreacted somewhat; certainly with regard to a curious period of 1980, when I became convinced that the White Lady of Dering had forsaken Pluckley for the wardrobe in our spare room. Although the stories and illustrations presented within are as chilling as I remember, the book frequently adopts a laudable stance of objective distance, and is filled with reminders for young readers to form their own judgements. “Ghosts are supposed to be the appearances of the spirits of the dead in a form visible to the living,” reads Chris’ introduction. “Whether they really do exist is still a complete mystery, but perhaps this book will help you to make up your mind.”

Elsewhere, there are accounts of “ghost stories” subsequently explained away as the results of flooded sewers and amplified alarm clocks, and – my favourite – the 200 metre-tall “Spectres of the Brocken” on the summit of a German mountain, which transpired to be the shadows of climbers, cast onto banks of cloud by a gently setting sun. The unambiguously-titled section “Sense or Nonsense”? even includes a bar chart displaying the results of an 1890 survey of 17,000 people; a mere 1,684 of whom claimed to have had a supernatural experience. Was all of this, I bravely ask, something of a Fortean approach?

“We adopted that,” nods Chris. “We stood back… we were the scientists. We were the researchers. And we just brought to the table the things that needed to be told and explained. We would have done exactly the same if we’d done a book about aeroplanes: we would have talked not as a manufacturer, not as a passenger, but purely in a factual way with that deadpan style… in fact, deadpan is precisely what it was! And my own feeling now, reflecting on what yourself and what other people have been saying, talking about your memories… I’ve come to realise the extent to which that approach made it possible for youngsters to engage with the material. Not because it was a rip-roaring story – they got their rip-roaring stories from somewhere else! – but because this was just factual, and their own imaginations could then pick that up and run with it and go… what if that’s real? Did I actually see that? What did my sister tell me that time? And that’s where, suddenly, the fascination comes in.”

Given this approach, is Chris slightly disconcerted that the book proved so terrifying to at least one unsuspecting seven-year-old?

“‘Thrilling’ works better for me than ‘terrifying’!” he laughs. “I would probably have been mildly shocked if someone said ‘You know… you’re going to scare the Bejesus out of kids.’ I wanted the kids to take something away, and feel that they owned a bit of knowledge, and had an insight into something about the world, an insight that may return fuller and more complete. They could sit down at the dinner table with their parents and expound… display what they had learned, talk about it, ask questions, ask their grandparents, run with it… that kind of thing. Start a conversation that would build upon this little pool, this little island of knowing that they had extracted.”

Since its publication, Ghosts has become a totemic symbol of the “haunted” childhood. The day after our meeting, I tweeted a photo of Chris holding up a rare, pristine copy of the original edition (a book I had to borrow from Usborne’s offices on the way to meet him; they’ve become an incredibly scarce collector’s item), and awaited the reaction. By the end of the day, 411 likes and 75 retweets later, I had been overwhelmed by a cavalcade of Proustian nostalgia from fellow children of the 1970s. “To the mid-forties set, he’s like our fourth dad – the other three being your actual dad (or stepfather or guardian), your favourite male teacher, and of course, Geoffrey from Rainbow,” tweeted writer and podcaster Paul Childs. “Chris Maynard is responsible for the person I am now!” added author and paranormal investigator Robert Johns, whereas fellow supernatural enthusiast Justin Cowell was merely full of gratitude. “I sincerely hope you thanked Chris for scaring generations of children,” he tweeted. “Some of whom were inspired enough to never stop being fascinated by this intriguing, delicious subject!”

Meanwhile, the most astute observation came from the shadowy mastermind behind the Things That Go Bump Youtube channel: “I bet Mr Maynard has no idea how many people consider him a hero and an inspiration…”

“No idea,” confirms Chris. “I’m over the moon. I mean, we all dreamed that what we were doing was important. We told ourselves that. We’d sit in the pub after work, and we’d say ‘you know… we’re knocking these books out, and yeah… we’re making life better. We’re giving kids tons of things to read.’ But we never could measure it. There were no ‘likes’, there was no internet, there was no social media, no real awareness.”

Ghosts was only one of “about 80” non-fiction books that Chris wrote in a twenty-year period from the mid 1970s onwards, and was published at a time that he now considers to be a halcyon era for the industry (“It was like producing music at the time of the Beatles and the Stones…” he tells me, “To be there, at that time… the golden age…”). And his level-headed but engaging approach to this most otherworldly of subjects clearly inspired a generation of budding Forteans, whose fascination with the likes of “Gef, the Talking Mongoose” (whose clawed paws I was convinced would one day poke through the cracks in my own bedroom ceiling, as the book’s alarming illustration suggested) has come to shape our adult pastimes and professions.

The 2019 reissue campaign began, curiously, in Finland, where – back in the 1970s – the book had been licensed to publishers Tammi, and published under the title Noidan Käsikirja. A Facebook group formed by Finnish fans gained almost 3,000 members, and led to an August 2018 reprint that sold out within a week; with the country’s latest sales figures now surpassing 18,000. Meanwhile, back in Britain, film director Ashley Thorpe and his Nucleus Films team contacted Usborne to request an interview with Chris; citing the book as a major influence on their forthcoming animated feature Borley Rectory, due for release this October. They found themselves in touch with Usborne marketing director Anna Howorth, herself a fan of the book, who was inspired enough to set up an online petition, hoping to convince the publishers that a UK reissue was a viable proposition. 1,000 signatories later, and with a promise in the bag from League of Gentlemen, Inside No. 9, and – indeed – Borley Rectory star Reece Shearsmith to write a new foreword, the deal was sealed.

“Again, amazement and thrill!” grins Chris, when I ask for his reaction, and he gushes with enthusiasm as I press him on the subject of the film. Although the infamously spook-plagued rectory itself is never mentioned by name in the book (there were, apparently, potential legal issues at the time), it clearly provided the inspiration for the “Haunted House” double page spread, detailing the trademark signs of a textbook ghost infestation (“an old skull screams whenever it is moved from the house”; “a bloodstain on the floor cannot be removed”), and Chris has been a willing participant in the film’s bonus features, with director Ashley Thorpe making a distinct impression on him. “A lovely guy from Exeter…” muses Chris, “who had in his school library a copy of the book that he took out regularly, and it lasted and stayed with him. He crowdfunded the various stages of the film, and part of the story that he told was his joy at taking a book that inspired him, and finally realising it in this wonderful animated film. And what he hadn’t expected was people then to say ‘Oh, I remember that book!'”

“We’ve broken down the walls of resistance to blowing off the dust from books that are twenty years out of date, and reissuing them like this. We’ve never had a revolt from below…”

Chris retired from full-time writing in the late 1990s, but is still clearly fizzing with energy and inspiration. In the two hours that we spend together, surrounded by the effervescent hubbub of the market stalls, he brims with ideas, anecdotes, thoughts and opinions: they tumble out of him, joyously, in a ceaselessly entertaining flood. “Two hundred years from now, people will be doing books like this about the ghosts of Old Spitalfields Market, and you and I will be sitting here,” he grins. “We are the hauntings of the future…”

As we part, and I begin the slow amble back to Liverpool Street station to return the original Ghosts book to Usborne’s bustling Farringdon offices, I feel the hairs on the back of my neck prickle. I whip around fast, but there is – of course – nothing there.

But thanks to Chris, I’ve still got the feeling.

The reissued edition of The World of the Unknown: Ghosts is available now from Usborne Publishing…

https://www.amazon.co.uk/World-Ghosts-Christopher-Maynard/dp/1474976689/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=usborne+ghosts&qid=1577725559&s=books&sr=1-1

Thanks to Chris Maynard, to Anna Howorth and Emma Baxter from Usborne, and to Tamsin Rosewell from Kenilworth Books.