(First published in Issue 117 of Electronic Sound magazine, September 2024)

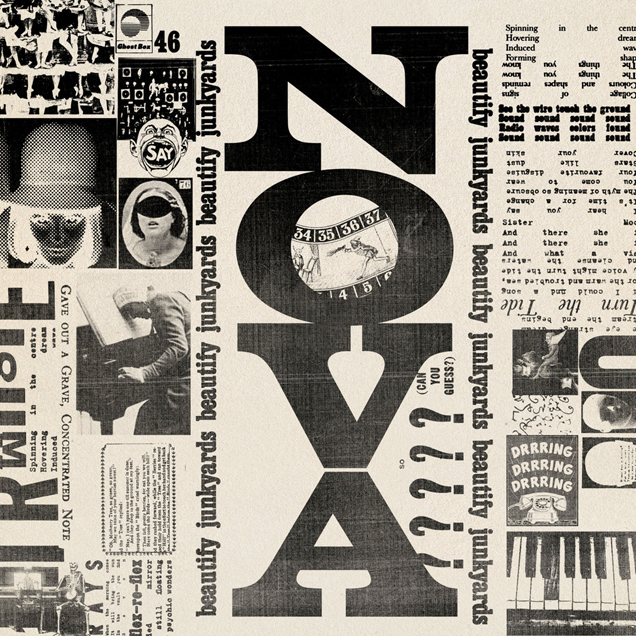

BEAUTIFY JUNKYARDS

Nova

(Ghost Box)

Imagine a stormy summer’s afternoon with clouds gathering outside the open window and a whiff of petrichor on the breeze. You’ve eaten one chocolate macaroon too many, curled up on the sofa and then – as weariness begins to subsume you – a song arrives from nowhere and begins to bob gently from side to side. It has Latin rhythms, electronic fizzles, and melodies that flit like an elusive butterfly, playfully refusing to be pinned down. Is it on the radio, or just drifting up from your subconscious? It’s hard to tell. Sleep is pulling you under, and that mercurial melody gets stranger by the second.

It could be pretty much any song on Nova. Beautify Junkyards’ third album for Ghost Box is aptly titled, with main man João Branco Kyron introducing a raft of new recruits. The breathy vocals of new singer Martinez are responsible for much of that dream-like quality. “Your song-like spell / Made rhymes in reverse,” she sighs amid the chattering beats of opener ‘Black Cape’, with fellow debutant Bernard Loopkin adding muzzy Radiophonic synths to the Lisbon-based band’s traditionally organic brand of swooning acid-folk.

And then things get really weird. Is that actual Paul Weller taking the lead on ‘Sister Moon’, or are the chocolate macaroons just kicking in? Nope, it’s the Modfather himself, a long-time Ghost Box fan lending soulful vocals to a song with more than a hint of his beloved Traffic. And as the sleep gets deeper, the breathing gets softer. ‘Groundstar’ is built around the mellifluous flute of Mercury Rev’s Jesse Chandler, ‘Somersault’ wraps Martinez in a Mellotron eiderdown and feels like a heart-rending homage to Trish Keenan and Broadcast.

As the lace curtains billow in the breeze, there’s one final player to introduce. Still indomitable in her ninth decade, Dorothy Moskowitz brings defiant sorcery to album closer ‘Turn The Tide’, a plea for the world to retreat from flame-filled madness. “If I could cast a spell with magic to restore / I’d whisper ancient words to every sandy shore,” she intones, then – as whoops of electronic fuzz subside – we’re suddenly pulled back to reality. The dream is over and there’s a rumble of thunder on the horizon, but a little glimmer of sunshine is now peeping through the clouds.

Album available here:

https://ghostbox.greedbag.com/buy/nova-75/

GHOSTWRITER

Tremulant

(Subexotic)

Some albums flirt with religious iconography, others have an actual practising bishop singing on them. Never one to do things by halves, Mark Brend has recruited Dr Andrew Rumsey, the Bishop of Ramsbury, to sing on this, his superlative third album as Ghostwriter. Accompanied by the equally strident voices of Suzy Mangion and Michael Weston King, Dr Rumsey lends authentic ecclesiastical welly to Brend’s startling arrangements of early 20th century spiritual songs.

‘Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down’ is a deceptively gentle introduction before ‘I Stand Amazed’ takes over, a ten-minute workout for wheezing organ and sound collage with soaring vocals woven immaculately throughout. ‘Often Forfeit’ adds darker, more discordant tones, while 16-minute closer ‘The Anchor’ turns an austere sermon into a drone-fuelled showcase for Mangion’s crystalline lead. “Will you anchor safe by the heavenly shore / When life’s storms are past for ever more”? It’s touching conclusion to a tranquil church of an album, a haven for silent reflection on a windswept clifftop.

Album available here:

https://ghostwriter3.bandcamp.com/album/tremulant

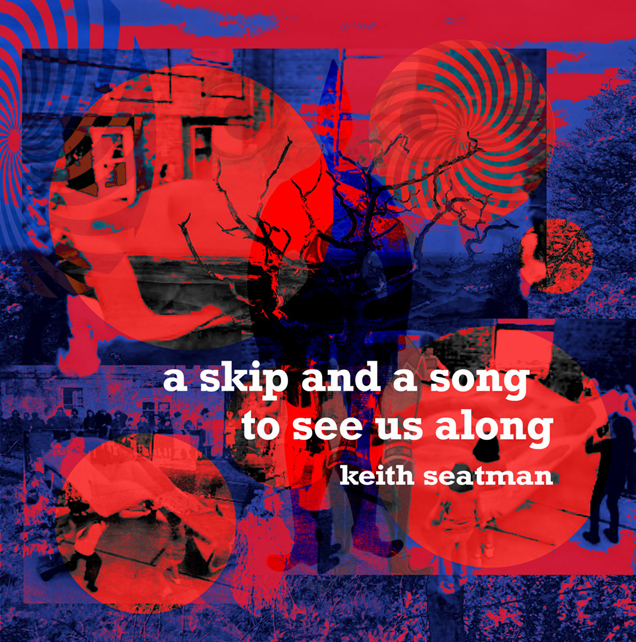

KEITH SEATMAN

A Skip And A Song To See Us Along

(KS Audio)

It’s hard not to picture Keith Seatman as the grinning denizen of a cobweb-strewn Victorian playroom, surrounded by faded whirligigs and grinning rocking horses that creak into sinister life as soon as the clocks chime midnight. A Skip And A Song To See Us Along is Seatman’s eighth missive from this antiquated world, an album evoking perfectly the giddy moment when Edwardian surrealism tipped over into lysergic psychedelia.

The fairground organs of the title track are the first rumbles of a wonky Ghost Train ride through the kind of tatty seaside weirdness that Seatman has made his own. ‘Perhaps All These Things’ adds Radiophonic swoops, ‘Ever Was Never The Optimist’ sounds like the music from some impossible Victorian arcade game, ‘Space Invaders’ powered by steam engine. The highlight, though? ‘Hickelty Pickelty’, where haunted house plinky-plonks hold together the shattered fragments of cut-up nursery rhymes. “There was a man he went mad / He jumped into a wheelbarrow / The apple pasty was too sweet / He jumped into a paper bag”. Brilliant, intoxicating nonsense.

Album available here:

https://keithseatman.bandcamp.com/album/a-skip-and-a-song-to-see-us-along

DREAM DIVISION AND THE LIBRARY OF THE OCCULT ELECTRONIC ORCHESTRA

A Rose In The Garden Of Winter

(Library Of The Occult)

Crikey! Who are the cowled figures we see approaching from the darkest corners of the abandoned churchyard, hands folded in demonic devotion? Why, it’s Tom ‘Dream Division’ McDowell and a cackling coterie of alumni from his splendid, horror-obsessed label, creating a grin-inducing tribute to a cinematic era when vampires came with glam-rock sideburns and Caroline Munro was given nothing but a skimpy negligee to protect her from the powers of darkness.

McDowell’s influences are not merely worn on his sleeve, they’re dripping down his arm into a silver chalice carved with serpents. ‘Black Rose’ has shuffling Brit-funk beats and throbbing organs, ‘Behind The Mask’ is a chaotic riot of fuzz guitars and groovy sitars. The likes of The Psychic Circle and Timmi ‘Garden Gate’ Meskers have helped McDowell realise his dream, and if you can’t listen to the descending Moroder-esque synths of ‘Blood Banquet’ without picturing Ralph Bates in a blood-splattered transept, then your soul is probably not worth saving.

Album available here:

https://libraryoftheoccult.bandcamp.com/album/a-rose-in-the-garden-of-winter

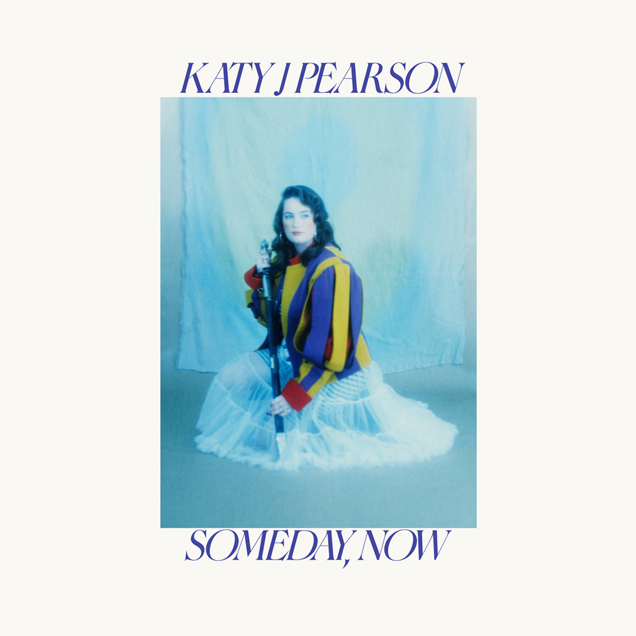

KATY J PEARSON

Someday, Now

(Heavenly)

Gloucestershire’s Katy J Pearson sounds sanguine on this charming follow-up to 2022’s Sound Of The Morning, sneaking complex emotions into irresistibly catchy choruses. “I’m not so tough / When you drop that bottle of grief,” she sings on ‘Save Me’, a tale of trauma-fuelled love underpinned by disco strings. There’s a perfect light touch throughout, with burbling synths and Johnny Marr-esque jangles, and highlight ‘Grand Final’ is a glorious dead ringer for 1980s Fleetwood Mac, stuck halfway between Tango In The Night and Stow-On-The-Wold.

Album available here:

https://katyjpearson.bandcamp.com/album/someday-now

HERON AND CRANE

Nestings

(Hibernator Gigs)

On their third album, Ohio’s Dave Gibson and Virginia’s Travis Kokas bring a world-weary edge to their trademark Byrds-go-synth wooziness. Opener ‘Ureshiku Mo’ (Translation: “Also Joy”) is appropriately jolly, and both ‘Morning Ritual’ and ‘Themes’ could be the soundtracks from crackly U-Matic video recordings of 1970s PBS educational shows. ‘On Fossil Beach’ and ‘Crownbeard’, however, add keening guitars to melancholy synths and suddenly darker skies are gathering. A wistfully psychedelic delight.

Album available here:

https://heronandcranemusic.bandcamp.com/album/nestings

SIMON CROCKET

Predecimal

(Bandcamp)

Lay off the LSD, man! After rummaging around the dusty sideboard drawers of Shoreham-by-Sea, Simon Crocket has crafted a warm-hearted synth homage to the era of pounds, shillings and pence. All three lend their names to track titles here, but it’s the strident ‘Thrupence’ that is the standout of this enjoyable collection, a throbbing Portishead-esque tribute to the most elaborate of Britain’s pre-decimal coins. ‘Sixpence’ and ‘Tanner’, meanwhile, both feel like Kraftwerk soundtracking The Ipcress File. Here’s hoping it earns him a bob or two.

Album available here:

https://simoncrocket.bandcamp.com/album/predecimal

ERSTWHILE FRIEND

We

(Bandcamp)

George Orwell? A johnny-come-lately. In 1921, Yevgeny Zamyatin created the grandaddy of 20th century literary dystopias for his novel We, and the oppressive regime of the ‘One State’ now inspires Leon Wilson’s slickly accomplished album of steely synth anthems. 1980s Radiophonic Workshop fans will detect the influence of Roger Limb in the elegant soundscapes of ‘Diagnosed With A Soul’, and the subtle chiptune melodies of ‘The Operation’ strongly suggest the secret police are compiling their files on a battered Commodore 64.

Album available here:

https://erstwhilefriend.bandcamp.com/album/we

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen