Afternoons used to last forever. Stillness would pervade, a sense of sweet torpor punctuated only by the pattering beats of a BBC test card or the austere parps of an Open University module. Raindrops might trickle down the window panes, motes of dust might float in rays of pale sunlight peeping through the front room curtains. The aftermath of illness often hung in the air: a sniffle, a cough, perhaps even mumps or chickenpox.

These listless feelings are captured perfectly in A Quiet Day, the second album by The Balloonist. It’s a project helmed by Ben Holton, who has been making music for over 20 years under an impressive collection of aliases. He has recorded as My Autumn Empire and Birds in the Brickwork, and also as the frontman of epic45, a band he formed in the 1990s with schoolfriend Rob Glover. And, since 2006, he has run Wayside & Woodland Recordings, a label whose releases have become synonymous with a very pastoral take on fuzzy childhood memory.

I caught up with Ben one appropriately quiet Friday afternoon to discuss these idyllic ramblings through tangled musical undergrowth. Here’s how the conversation went…

Bob: Let’s talk first about The Balloonist. This whole project was inspired by Mr Benn, wasn’t it? There’s an episode just called ‘Balloonist’, where he takes part in an Edwardian hot air balloon race.

Ben: Yes! It goes back to 2005, around the time we were working the fifth epic45 album, May Your Heart Be The Map. ‘The Balloonist’ was just a single track that I’d recorded for a side project, inspired by a Mr Benn video that Anthony Harding from the band July Skies had given to me. He’d pointed out that ‘Balloonist’ was one of his favourite episodes, so I remember concentrating a bit more on that one. It’s amazing – there’s only a short sequence of the balloons in flight, with a little piece of music that only lasts a few seconds, but it all very much inspired the track I wrote.

A few years later – probably about ten, in fact – I started working again on music that put me in mind of that track, and that headspace. So I thought The Balloonist would make a good overarching name for it all. It’s about a very specific set of childhood memories that have recurred and haunted me for years.

You’ve come to the right place. Tell us more…

In essence, they’re quite mundane. And I’m sure other people have similar memories. But we’re talking pre-school, or days off from school – sick days, or Bank Holidays. Those days when it’s really quiet and nothing is happening. I’m pretty much alone in the living room… maybe my mum has a friend over and they’re nattering in the background, but I’ve just got the TV on. And I guess it’s also about the tones and textures from that period. We’re talking the mid-1980s, so it’s formica tables and heavy curtains, that slight overspill from the 1970s. Sorry, it’s so strange, trying to put these feelings into words.

Not at all, I know exactly what you mean. When I go on podcasts, I sometimes get asked if I can describe the feel and ethos of hauntology. And I always say “Try to remember how it felt to be off school on a rainy Tuesday afternoon, watching the Open University on BBC2… with chickenpox”.

Totally! Why does that resonate so much? I don’t know. And the funny thing is… it’s not as though, at some point in my adult life, I decided to look back and think “Oh, those were strange times”. It’s always been there. I had those feelings as a kid, and I was really enchanted by those programmes. I think a lot of them were from a few years earlier, so in 1985 I’d be watching a Schools programme from 1977. And just perceiving the differences in things like the film stock really fired my imagination.

I’ve occasionally been accused of applying adult revisionism to my memories of feeling “haunted” as a child, but I honestly remember trying to come to terms with those feelings when I was little. I remember, aged about four, telling my mum that Bagpuss made me feel sad but I didn’t know why.

I can totally understand that!

There’s a track on the new Balloonist album called ‘Pebble Mill At One’. I assume you have very distinctive memories of that programme, too…

Oddly enough, the memory that immediately pops into my head is quite odd. It’s me doing a headstand against the sofa, completely naked, while Pebble Mill At One was on. The funny thing is, I was 28 years old at the time…

Wahey!

No, I was six or seven. Why that’s my overriding memory, I’ve no idea. But yeah, I remember watching Pebble Mill At One and being excited if there was a Doctor Who actor on it.

What the new Balloonist album really encapsulates is the feeling of boredom that pervaded the pre-digital childhood. Days when there was literally nothing to do, but that boredom could actually fire your creativity. You’d write a story, or draw a picture, or just look out of the window and daydream. I’m not sure those feelings exist so much any more. In the age of the smartphone, console games and social media, I don’t know if it’s actually possible to be bored in that way again.

I entirely agree. I’ve got a ten-year-old son, and he just doesn’t have a break from input. I try to be in control of that to a certain degree, but you really can’t. Once they’ve discovered Youtube, that’s it. I’ve maybe tried on occasion, slightly experimentally, to say “Turn that off, and let’s just sit for a while”. But it’s just an entirely different set-up for kids now.

And in some ways that’s great. If I was a kid now, I’d love it. But I do think we’ve lost a certain sense of stillness and silence – and those things can be very healthy.

I think so, too. When I was a kid, I used to go and stay with my gran in South Wales. I think I was basically dumped there to get me out of the way! And I recently found a postcard that I’d sent to my dad when I was about nine, complaining about being bored. So it wasn’t all beautiful, dream-like moments… it was often “there’s nothing to do here!”. When I found it though, I was a bit angry at my younger self. You’re bored? It’s the late 1980s, go and see what’s on telly!

Are you old enough to remember the old-school British Sunday? You can’t even begin to describe it to anyone under thirty. Your local newsagent might open for a couple of hours in the morning to sell the Sunday newspaper, but apart from that every single shop was shut all day. There was no public transport either, and the telly was basically religious programmes and farming news. If it was raining outdoors, there was literally nothing to do but sit there at home.

Yes, everything ground to a halt. I’m sure you’ve talked about this before, but there was a certain gloom to Sundays. Especially in the evenings, with that heavy, pre-school vibe. Last Of The Summer Wine… which I know you love! And I do, too. But there were times when that theme tune felt really painful.

Tell me about epic45, the band you formed with Rob Glover. I didn’t quite realise how far back the band went – you formed in the mid-1990s, didn’t you? Did you and Rob meet at school?

We did, yeah – in the first year of primary school.

Wow! So you’ve known each other since you were four or five?

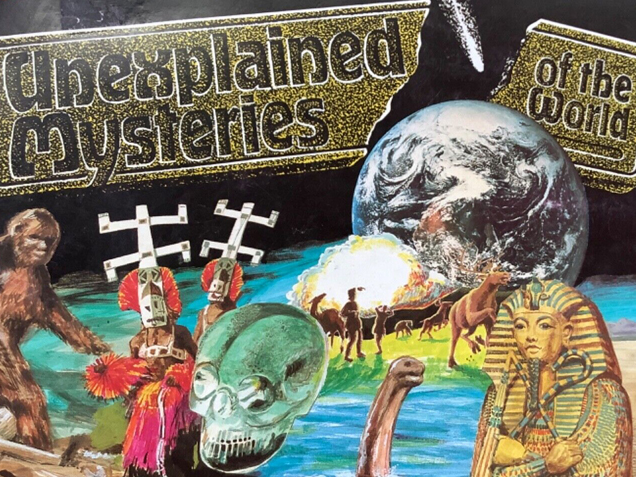

Yeah. We went to St Mary’s Primary School in Wheaton Aston, the village where we both spent pretty much our first thirty years. I think it was music that bonded us as friends – we were both Pet Shop Boys fans. But also things like the Usborne Book of Ghosts and… what were the cards that came with teabags? Unexplained Mysteries of the World?

Oh! Was it Brooke Bond? Or possibly PG Tips?

It could have been PG Tips (NB – it was!). You’d get little cards with mysteries on them… that photo of someone sitting on a bench with hands coming round the back of it, or the ghostly monk standing in a church. We’d sit and look at these things together, and we had the same way of thinking about these things. Our school was an old Victorian building, but with a 1960s extension, and the playground was opposite the old schoolmaster’s house. We used to look up at the top window and convince each other there was something moving up there! And there was a little brook down the lane from the school, so we’d create stories about a troll living under the bridge.

There’s also a Children’s Film Foundation film called One Hour To Zero. Whenever we caught that on TV, it was a magical event. But for some reason, the character played by Dudley Sutton really spooked us out. We found him really sinister and odd. We didn’t know his name, we just called him The Man With the Curly Hair – and we’d convince ourselves we could see him around our local farmland. “There he is! The Man With the Curly Hair!” And I guess all of that grew into a friendship.

Me and my mates did exactly the same thing. We filled the local woods and fields with the weird beasties we’d seen in Doctor Who. It sounds like we grew up in very similar places – small towns surrounded by farmland.

Yeah, Wheaton Aston is pretty small. It’s not a picturesque village, it’s actually quite scruffy. Or it was, it’s been tidied up a bit now! Parts of it almost feel like any identikit suburb now – it’s an old village, but only a few of the oldest buildings remain. My mum and dad moved there from Wolverhampton in the early 1970s. Dad was a plumber, Mum was a nurse and it was still a time when it was possible to move out into a country village. It wasn’t that expensive. For which I’m forever grateful, it was a lovely childhood.

Was it a musical upbringing at all?

Yeah, both my mum and dad loved folk music, and they ran a folk club in Wheaton Aston Sports and Social Club. They both played guitar as well, so folk clubs and festivals were very much something I grew up with. I’d hear Fairport Convention and Joni Mitchell, and my mum still had a lot of her 1960s records.

That’s how I discovered the Beatles. I’d sit on my own with a pile of records, playing random 1960s pop singles, one after the other. The Beatles just captured me, although at that point I didn’t know who was who…

I was the same. They all had the same haircut.

That was it! A lot of the time, I thought Ringo was John, and I’d be looking at Ringo’s face when John was singing. I had two older brothers too, and there was quite a gap – the middle brother, Mathew, is seven years older than me. He loved the Pet Shop Boys, which is probably where I got it from… plus New Order, Depeche Mode, Soft Cell and the Human League. Then, in the late 1980s, it was the Happy Mondays and Acid House. But he also liked indie bands like the Wedding Present. My oldest brother Tim liked Guns N’ Roses, who I never liked very much… but he also liked REM and Neil Young, who I love. And it was Tim that bought His ‘N’ Hers by Pulp, which is one of my favourite albums of all time. It’s quite an important album in my life – it even touches on some of that strange surburban nostalgia.

So how did epic45 come out of this melting point of musical influences?

Rob and me went our separate ways after St Mary’s Primary School – we went to different middle schools, then we met up again in high school. By which time we’d both got very much more into music. Rob’s family had MTV, so he was exposed to a bit more contemporary stuff. I didn’t have MTV but my two older brothers had given me an alternative education! So we started a band in 1995, when Britpop was everywhere. I liked Oasis at the time – I had the first two albums. And I still love Blur, so that was mine and Rob’s common ground. The first iteration of epic45 was just standard indie… we couldn’t really play our instruments very well, we just learned together. It was Rob, me and the drummer Mark. And I wasn’t a songwriter, so it was just us jamming and making riffs. I was into Tricky and Portishead and The Prodigy as well, so I tried to make some electronic music on my brother’s Commodore Amiga, but I couldn’t do it very well.

Then, after a couple of years mucking about, we saw Mogwai on the NME Brats Show on Channel 4. We were 16 or 17, and it was a watershed moment. We needed something to inspire us out of the indie thing, and suddenly Mogwai were onstage playing this really pretty melody that then turned really heavy… and there was no singing! It was like “Oh, OK… we don’t have to write songs, then?”

And how did the Wayside & Woodland label come into being?

We released our first 7” single on a Birmingham indie label called Bearos, in 1999. We did a couple more with them, and a couple more on other indie labels, then we met a guy called Scott Sinfield, who lived in Stafford. He was about ten years older than us, and he’d say “You remind me of Slowdive or Bark Psychosis”… bands we hadn’t heard of, but he introduced us to them! Scott had the idea of setting up a syndicate record label called Make Mine Music. Basically, it was a collective where everyone made and paid for their own music, but it was be released under that umbrella name. That was in about 2002. Eventually, we just thought that instead of running our music past other people – not that that was ever a problem, really – we could just release it ourselves. So we came up with Wayside & Woodland in 2006, and it was only ever intended to be a small thing. The first Wayside & Woodland release was a limited edition of one!

And who’s got it? You or Rob?

Neither of us! My friend Tom has it. My mum also ran a music festival in Wheaton Aston…

(NB: This photo shows Ben’s mum playing at Wheaton Aston festival alongside friend and co-founder Julian)

A folk festival, I’m guessing?

It started out that way, but she didn’t like calling it a folk festival! She tried to bring in elements of world music, and Rob and I had our own stage down the Sports and Social Club – something that eventually became the Wayside & Woodland night. That’s where we sold the label’s first few CD-Rs, and our first proper release: a 12” single with two epic45 remixes on it. One by Bracken, who was Chris Adams from the band Hood, and the other by Steven Wilkinson, who goes under the name Bibio. At the time, he’d just been signed to a US label called Mush. He’d sent a tape to Boards of Canada, who liked it and sent it onto the label! He ended up on Warp Records, but it was us that released his first vinyl record and – even though he doesn’t really play live any more – he played at our festival twice.

So the label started there, and it just built up very gradually. After Make Your Heart Be The Map came out, one song – ‘The Stars In Spring’ – got added to a couple of playlists on Spotify, and ended up with about 27 million plays! So all of a sudden, some quite significant wedges of money were coming in every month. And we turned Wayside & Woodland into a limited company so we could keep it all above board.

It’s good to keep on the right side of HMRC, isn’t it?

I think so! And that enabled us to expand the label and look at releasing music by other artists. Whenever you’ve got a bit of money to play with, it’s easy to splurge out on things… but you soon learn. That Spotify money doesn’t come in any more, so I’m now just trying to keep the label going month by month. Until about a year ago, it was me and Rob running the label together, but then it just become me. It was all amicable and very understandable – it was just life. Rob has his regular work, and his own Hidden Britain project.

It’s lovely that you’re still mates after all this time. You work well together – Rob’s artwork really complements the music you put out.

Definitely. The visual aspect has always been an important part of the label’s ethos. My photography and Rob’s design.

Your photography is really interesting. You put out a lovely book – with accompanying music – in 2021 called Birds In The Brickwork, very much exploring the aesthetics of the “edgelands”. Those neglected places on the edges of towns and cities. Industrial estates, allotments and overgrown canalsides. What is it about those places that appeals to you?

It’s really hard to put my finger on it. It’s like talking about The Balloonist! I think it’s all linked in some strange way, though. There’s probably a brilliant academic study about all this. I think some of is connected to the way I viewed the world as a child – trying to find something magical in mundane places. And that’s how I still see the world. That approach has kept me going a lot of the time. My dad was a plumber and I’d often go to work with him, I’d ride along. And he’d visit industrial estates to pick up bits of piping while I waited in the car. I just loved looking at warehouses on the edges of scrublands and fields. It’s difficult to describe that feeling, but I’m always chasing it.

And there’s just something really haunting about the suburbs. So much life is contained within those ordinary-looking buildings. What’s going on inside them? It could be terror, it could be pure joy. I made a My Autumn Empire album called Oh, Leaking Universe, about how mundanity masks the complexity of the infinite universe. Every little detail just contains so much information. It’s so hard to explain though, which is probably why I usually make music about it rather than talking about it!

You’re a fan of George Shaw, aren’t you? His paintings sum up these feelings perfectly, I think.

I love George Shaw. He’s from Coventry, so when you know the scenes in his paintings are not too far away, that gives them something extra. He uses Humbrol paints from Airfix models – it’s incredible! I saw an exhibition of his a couple of years ago, and to see his paintings in the flesh was so amazing. The textures and the colours. His paintings are 100% an inspiration to me.

I loved that feeling of exploring as a kid, too. Your world is so small as a child that you never have to roam very far to find somewhere new, even just a little pathway that you’ve never seen before. I’d follow tracks into the woods and hedgerows and find myself in bits of unfamiliar wasteland with sheets of asbestos lying around. And a goat nibbling at the weeds. And it felt magical, like I’d passed through a portal into another dimension.

That’s exactly it. I was always exploring with a couple of friends – Rob, and other mates. And that’s what we’d do – we’d just go off, walking around. I loved finding traces of human activity in places that were a bit odd. An edgeland, in essence, is somewhere you pass through. It’s functional. But objects can be left there, and those are the things that fascinate me.

St Mary’s Primary School closed down in 1993, and the parents were all really angry, because we were going to be sent to Brewood, a neighbouring village. So we’d have had to get a bus! Some of the parents formed a committee against it, and sent their kids to Penkridge Middle School instead – a village in the opposite direction. But I spent my final year of middle school in Brewood, so was split up from Rob!

The first year of high school, when I met up with Rob again, we went back to St Mary’s Primary School for a look around. The Victorian part was being turned into a house, and the modernist part was just boarded up. But somebody had broken a window, so we climbed through and started exploring. We hadn’t been inside that building for five years. We jumped into the hall, where we’d done sports, and it still had the pull-out apparatus – I used to love it when that came out! And a pile of crash mats, and an overhead projector. Which I wish I’d taken, although I might have had trouble getting it home! A lot of stuff had been left there, it was just an amazing experience.

We went in there a couple of times, and Rob later brought a couple of his friends from Penkridge. Which I’d say was a slightly rougher place, but they were decent lads. And there were some high jinks – they had no history with the school, so they possibly had a bit less respect for it! We went into the head teacher’s office, and there were a load of keys laid out in a very orderly fashion. One of the kids scooped them up and put them in his pocket – I’ve no idea why. Then he threw them into the churchyard. Sorry, there’s no real exciting end to this story… [laughs]

(NB These pictures are screengrabs from a 1980s VHS, and show Ben and his class hard at work during a “Victorian Day” at St Mary’s Primary School!)

The last epic45 album, You’ll Only See Us When The Light Has Gone, painted a slightly less idyllic picture of suburbia. One where the paint is peeling, and tensions are rising.

Yeah, definitely. I think that’s been an element of epic45 since the album Weathering. Although I’ve never tried to make it about idealised childhood memories. People have written about it in that way, but for me it’s very much a dichotomy: of memory and of the reality of the world we live in at present. The new album is the most song-based epic45 album, and it’s a slightly more muscular sound, but it’s all still observation and reflection. I didn’t want it to be overtly political. There’s no judgement.

You’re clearly saddened that the country has become more divided, though.

Yes, that’s sad. Anyone who is saying really hateful things is unhappy really, aren’t they? I’m not excusing what people do, I’m just trying to understand it. Where I live now, on the edge of Wolverhampton, almost feels like an edgeland. The first line on the album – “Harsh words by the school gate” – is a direct observation of the people I speak to there. We are divided, and I think social media has fuelled that. People let it influence how they behave in real life.

So what’s next for you?

The Balloonist album is coming out! I’ve tried to make it look like a proper 1980s CD, even down to sourcing the right back trays. It’s meant to look like a late 1970s album that has been reissued on CD. After that, I’m working a zine in the same format as the Birds In The Brickwork photobook, and I’m looking for contributors. Artists, photographers and writers. I’ve already got a few pieces lined up for it, and ideally I’d like this to be the beginning of a regular thing.

I’m releasing an EP in May by a friend of mine, too – an amazing artist called E.L Heath. It’s called Cambrian, and I think you’ll like it. And there’s also a band from Wisconsin called Bell Monks, who sent me an album last year sometime… they said they were quite influenced by epic45 and it just floored me! I thought it was an absolutely beautiful album. It’s very much landscape-inspired, very slow and beautiful music. I’m really excited to release it.

It sounds like Wayside & Woodland has become a full-time job for you?

Basically, yes. I’ve got a bad back and I’ve had to leave my regular job as a healthcare support worker for adolescent psychiatric patients, so I’ve been doing this full time! Which is great, really. Great things can come out of crappy things, and I love it.

A Quiet Day by The Balloonist is available here:

https://waysideandwoodlandrecordings.bandcamp.com/album/a-quiet-day

Find out more about Wayside & Woodland Recordings here:

http://waysideandwoodland.com/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen

Thank you for such an interesting article about Ben, who is not only a talented & inspirational composer, but also my son. I remember so well those formative days, & even at about the age of about 3yrs him pulling me to listen to the shower dripping & also the sound of the wind outside which was music to his ears. He composes from his heart & soul & it’s great that someone identifies this & shares. So again thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for interviewing Ben. I met Ben’s mum around 1997, on a holiday in Greece when Ben was about 16 (I was exactly in between both their ages, so I was like a human Venn diagram musically and culturally with them). Ben had a friend with him, who I think must’ve been Rob. I always knew Ben had a unique angle on the world. We drove around on this Greek island and randomly spotted this huge deserted soft toy (it was ginormous) of a sad-looking dog that had been dumped by the side of a gravel path in the middle of nowhere. Ben and Rob (?) totally got the weird melancholy of that. I stayed in touch with Hilary. Later, when I visited her in Wheaton Aston, I asked Ben what he was up to and he said he was watching film footage of ‘pylons in the rain. In Japan.’ I realised then that Ben’s understanding of the hauntological aesthetic was well-formed. I’d love to see them both again.

Kerri

LikeLike

Thanks for posting this interview. I’ve been a fan of Holton and his contemporaries (e.g., July Skies) for decades now. I find it fascinating how their music, with its very specific references to British locales, TV programs, etc., deeply resonates with my own childhood memories of the ’80s — even though I’ve lived my entire life in Nebraska, smack dab in the middle of the USA.

Holton et al. tap into something universal with their music, and I always look forward to the next release.

LikeLike