(First published in Issue 97 of Electronic Sound magazine, January 2023)

THE MINISTRY OF TRUTH

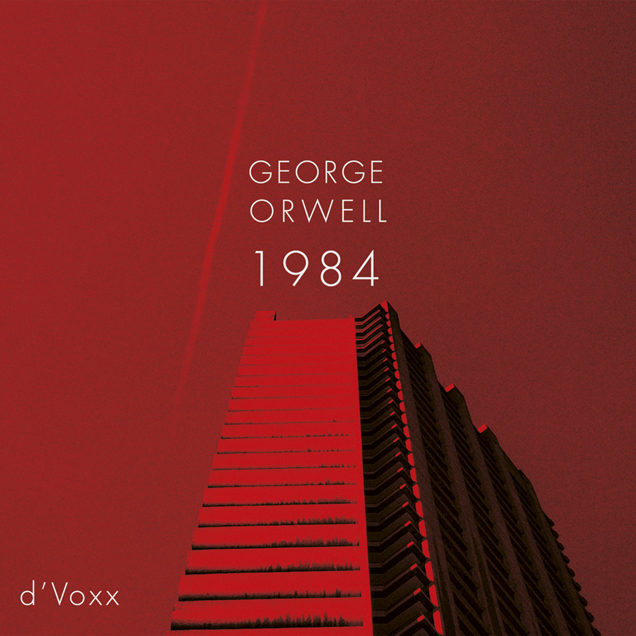

In a world taking some distinctly dark turns, George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984 feels alarmingly prescient. Nino Auricchio and Paul Borg are d’Voxx, and – amazingly – they have succeeded where David Bowie once failed. With an officially-sanctioned musical homage to Orwell’s most celebrated work

Words: Bob Fischer

“I studied 1984 at school, and it felt like a vision of the future that had thankfully never come to pass,” explains Nino Auricchio, leaning on the console of an impressive studio set-up. “Now, unfortunately, things appear to have taken a darker turn. We’re slipping more and more into areas where there’s a danger of totalitarianism. The assault on truth, and people taking control of information when they really shouldn’t have that ability. We wanted to explore that.”

“I think if you’re a certain age, 1984 was a staple on the school curriculum,” adds Paul Borg. “But – as Nino says – it was a retrospective look at what might have been. We read it from a safe position, and it felt like an old novel about something we’d come close to… but it never quite happened. So who would have guessed we’d come back to it in the way we have?”

They’re talking from adjacent Zoom windows, and we’re all hoping Big Brother isn’t watching us. Although Paul’s jazz-influenced kittens, Mingus and Django, are making their noisy presences felt. Since 2015, Nino and Paul have been making modular music together as d’Voxx. Their 2019 debut album, Télégraphe, was an upbeat, Berlin School-influenced journey through the interconnectedness of underground metro stations. The follow-up, however, is a distinctly darker voyage through George Orwell’s premonition of a dystopian future, where the authority of the state is both merciless and total.

“People in their forties, fifties and sixties grew up in a time when things were quite stable,” continues Paul. “That period between the Second World War and the 21st century was an era with a strange sense of certainty… in Western civilisations, at least. But the history of the world is not stable, so we were misled. And all those certainties have been taken away in the last six or seven years. So maybe what we’ve returned to is actually the norm? It’s a scary thought.”

“After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it seemed like the wars were won,” agrees Nino. “Neo-liberal monetarism and social democracy had triumphed, and everyone was allowed to do whatever they wanted. But, for the last 30 years, we’ve been spending that post-war dividend hand over fist, and now it’s run out and we’ve gone back to what the world was like before. You do worry about the future of your kids.”

The album is starkly beautiful, weaving spoken extracts from the original Orwell text into elegant suites of modular synth, all underpinned by sympathetic sound collages. Including, Paul reveals, field recordings of primitive 1940s computers, still “clicking away” at Bletchley Park.

And, amazingly, the duo have succeeded where David Bowie once failed. In 1973, Bowie abandoned plans to adapt ‘1984’ into a stage musical when Orwell’s widow, Sonia, flatly refused to grant him the rights. The disgruntled rock star later described her as “the biggest upper class snob I’ve ever met in my life” (although there’s no evidence they did actually meet) and the songs Bowie had already written were swiftly retooled for his Diamond Dogs album. Five decades on, d’Voxx had more luck: both the Orwell estate and Penguin Books were happy for the duo to produce an officially-sanctioned musical homage.

“I think when we made it clear we were quite a niche project and not some mainstream act, that helped,” smiles Paul. “We were only releasing small numbers, doing it purely for artistic endeavour.”

“And we didn’t want to hit all the cliches,” says Nino. “So there’s no Room 101 or Big Brother.”

“That’s why we went back to the original text,” adds Paul. “To re-read and see what resonated in a contemporary sense. The opening track, ‘Airstrip One’ is quite disturbing. You hear children being bombed. Something that is happening right now, and it’s getting closer and closer to Western Europe. When I hear that track, I’m still uncomfortable with it – and that’s important. I’m glad it makes me feel that way.

“We started this album three years ago. Télégraphe had been such a celebration of the global network, and the idea of making connections around the world. It was the positive side of an interconnected world. A celebration. But then Brexit, Trump and Putin happened, and we didn’t feel like making a happy album.”

Their lament for global interconnectedness is fuelled by decidedly cosmopolitan upbringings.

“I was born in Stratford-Upon-Avon with an Italian father,” says Nino. “He was a professional guitarist who had played all over the world, then came to the UK in 1974. He was working in Cyprus when the Turks invaded, and the British Embassy flew out all the foreign nationals. So he came to RAF Brize Norton and worked in London – playing in Greek restaurants, because they wanted live music six nights a week. He met my mum in Stratford, and the rest is history. I moved around an awful lot as a kid – to different parts of the UK, and back to Italy for a while. I think I’d moved 13 times by the time I was 18.”

“Whereas I’m from North London, born in Islington,” says Paul. “But my father is Maltese, he came to this country after the war.”

So let’s ask a cheesy question. Where were they both in the actual year of 1984? For seasoned producer Paul Borg, the answer is eyebrow-raising, and the story begins in the previous summer. Reinforce the floorboards, everyone… there are some serious namedrops here.

“In 1983, I was 15 and I needed some pocket money for the summer holidays,” he recalls. “A friend of mine said ‘Go down the Job Centre and say you’re 16… they never check’. So I did, and I must have told them I was into music. Because, in the Roundhouse Studio in Camden, Haircut 100 and Kajagoogoo were both recording and they’d lost the file of applications for assistant engineers. So one of the guys from Haircut 100 said ‘Let’s phone the Labour Exchange, and see who we get. That’ll be a laugh…’

“The next day, my mother came to find me fishing on Hampstead Heath and said the Job Centre had phoned asking if I’d like to make tea in the studio. So I spent three weeks working with Jim Lea and Noddy Holder from Slade, with Lemmy from Motörhead also floating around. But then I had to go back to school.

“In 1984, though, I went back. I literally left school on the Friday, and on the Monday morning Stevie Wonder was there, recording the vocals for ‘I Just Called To Say I Love You’. That was my first full day at work. I asked if he wanted a cup of tea, and he said ‘No, I’m cool, man – I’ve got peppermint and hot water’. And we were all amazed because he had a Braille DX7…”

Bloody hell. Nino, can you match this? He’s laughing raucously at his bandmate’s splendid showbiz yarns, and then – with a gleeful lack of mercy – makes the pair of us feel ancient.

“I was four years old in 1984,” he beams. “But I was mad about electronic music as a kid, and I grew up listening to Mike Oldfield, Jean-Michel Jarre and Jan Hammer. At the age of seven I wanted to learn the piano, so I had lessons that continued all throughout school.

“Then I got into teaching, while doing other musical bits on the side. I found myself making funk albums with a band called Funkshone. We toured all over Europe and did some absolutely bonkers gigs. One was at an Exteme Sports festival on a floating pontoon, being towed up the middle of a Norwegian fjord. And we were invaded by teenagers dressed as pirates…”

“Norwegian pirates?” asks Paul, incredulously.

“Well, Vikings, I guess. Later that day, we were meant to be supporting Earth, Wind & Fire, but they didn’t turn up. So we headlined. I imagine they found a place selling nice cinnamon buns and didn’t want to leave.”

They’re a great double act: bright and breezy, and generous with laughter at each other’s anecdotes. Even before their first meeting, they’d amassed mutual friends and contacts through adventures in the jazz-funk world. After cutting his teeth in the studio with Rebel MC, Derek B and Yazz (“I’ve got a double platinum disc somewhere”), Paul had spent much of the 1990s working with Gilles Peterson’s Talkin’ Loud label. By 2005, both were teaching at the University of West London, and met for the first time at a degree show in Brick Lane.

The friendship eventually morphed into a musical partnership. Partially inspired, curiously, by the decidedly non-funky phenomenon of Numbers Stations: mysterious sequences of numbers broadcast internationally on shortwave radio frequencies throughout the 20th century. Although often assumed to be instructions for spooks and spies on covert operations, their true nature has never been officially revealed. But these plummy-voiced snippets, couched in static and interspersed with stark electronic jingles, remain evocative curios from an era riddled with Cold War paranoia. An extensive set of off-air recordings, primarily made by Irdial Discs founder Akin Fernandez, was released as The Conet Project in 1997.

“Back in 2015, Nino and I had a project called Cold Waves,” recalls Paul. “And he mentioned Numbers Stations to me. I used to listen to those when I was a kid to scare myself to sleep! So we came up with a Max/MSP patch that allowed us to sonify the recordings captured by The Conet Project. And in 2016, we performed it at the Funkhaus in Berlin.”

“Yes, and we drove there!” adds Nino. “On the way back, we thought ‘What should we do next?’ And that was the beginning of d’Voxx.”

Three years later, Télégraphe was released, via Ian Boddy’s legendary imprint for underground electronic music, DiN.

“Ever since I started listening to instrumental electronic music as a teenager I’d wondered – what the hell do you call your tracks?” recalls Nino. “So I had the random thought of naming them after different underground railway stations. The idea of these networks connecting seemed to fall into place alongside the modular connections of the music. And we decided to include segues between the tracks: trains would arrive at the stations, and there’d be an announcement.”

“And the stations are from all over the world,” continues Paul. “So you travel from a Chinese station to a German U-Bahn to the Paris Metro. It’s a really abstract journey, and people have said that, when they listen to the album on an actual train, it’s very confusing…”

And are their students aware of their musical escapades?

“We make sure they are!” laughs Nino. “Paul and I actually wrote a module called The New Modular Music, which we’re delivering across the electronic music courses here at the university. The students are used to making music on laptops in their bedrooms, so using actual hardware is something they initially find really difficult. But, after a while, they start to see it as a completely new way of working.”

“Which lends itself to interesting live performances,” adds Paul. “They’re physically moving around, plugging in cables to make something happen. And when we play live, me and Nino now set up our systems opposite each other, so we’re able to communicate with each other and improvise.”

“When we first started performing,” Nino continues, “Paul and I were next to each other with our modular suitcases. We’d open them up in front of us, and we’d look like two guys who’d gone on holiday and were unpacking their clothes. So we decided to go side-on. We could finally see each other, and… oh, look! Actual cables! And there’s a certain amount of ego, too. We like to be onstage, projecting ourselves. It’s about having fun, but it can also be ‘Yes, we’re very serious’. That Philip Glass stare…”

He glowers with a furrowed brown into his webcam, and there are chortles all around. But, when it comes to the crunch, they are very serious. Certainly about 1984, and the political apathy and post-truth misinformation that has allowed 21st century Orwellian “doublespeak” to flourish.

“You’ve got a whole group of the population who don’t care any more,” says Nino, despairingly. “They don’t know what’s real and what isn’t. It’s ‘Leave us alone in our homes to watch Matt Hancock eating kangaroo cock in the jungle…’”

“There’s a serious point to that, too,” says Paul. “They don’t want people educated. I first noticed the gaping gap in my own education in the 1990s, when I was working in France for a while. Everyone in France had a grounding in philosophical ideas, and would question things in a healthy way. I don’t think that exists here, or in the States.”

Their crusade to redress the balance has been supported by a label boss who is fulsomely supportive of their work. Both are fervent in their praise for Sunderland electronic maestro, Ian Boddy. How did they make first contact?

“He was a face at all the modular festivals,” explains Paul. “I think I rudely interrupted a conversation he was having with Robin Rimbaud and I remember him giving me an evil glare. Ian does scare me a little bit, but in the nicest possible way. He’s an amazing guy, and he gives a voice to a lot of artists who work in electronic music.”

And on that heartwarming note, we retreat back into our own personal dystopias and call it a day. Paul needs to let the cats out, too.

“Hopefully the next time we talk, things will be slightly be more cheerful,” he smiles. As one of his biggest-selling musical collaborators once succinctly put it, the only way is up.

1984 is available here:

https://din.org.uk/album/1984-din

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen

Slightly puzzled that the artists needed the permission of Penguin and Orwell’s estate to release this album when the original text version of 1984 entered the public domain January 1st of this year.

LikeLike