“Please treat the church and houses with care. We have given up our homes, where many of us have lived for generations, to help win the war and keep men free. We shall return one day, and thank you for treating the village kindly.”

The note was elegantly handwritten and pinned to the church door immediately before Christmas 1943. For the 225 residents of Tyneham, a tiny village close to the Dorset coastline, it was a forlorn hope. Their homes, they were told, were being temporarily requisitoned by the Ministry of Defence for wartime exercises. But the villagers were never allowed to return, and – eighty years later – Tyneham remains uninhabited, its homes and buildings ravaged by time, nature and decades of military training.

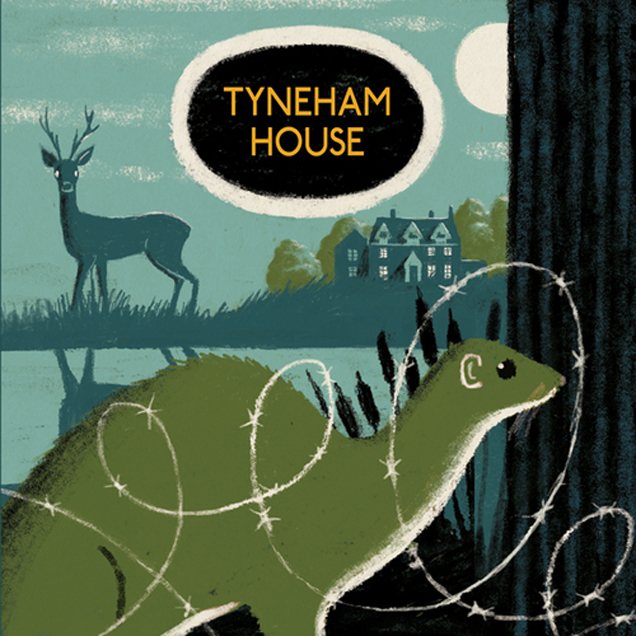

In 2012 an anonymous album, simply titled Tyneham House, became one of the earliest releases on the nascent Clay Pipe label. A soothing pastoral lament performed on acoustic guitars and mellotron, it captures perfectly the stillness and the sadness of this timeless place.

The album is the collaborative work of two artists. I knew the identify of one of them, and tentatively contacted him enquiring about an anonymous interview. He was delighted to agree on behalf of both him and his collaborator, and asked if we could conduct the interview via Twitter DMs. So what follows is an interview with both Tyneham House musicians, but presented – at their request – as the thoughts of a “unified entity”. And I still have no idea about the identify of the “other” artist involved…

Bob: Have either of you actually been to Tyneham? If so, I’d love to know your impressions and memories of the place.

Tyneham House: It’s a highly suggestive landscape that deserves to be thought of as more than a loose collection of ruins. Certainly when I was growing up, before it was sanitised and it was still a breeding ground for leftover ordnance, the further reaches of the fields yielded tangible hints of human existence that you didn’t get at a Tudor castle or a stone circle. A teacher’s bicycle still propped up near a back door. Broken mustard pots on the banks of the stream. It made it an easier and sometimes disconcertingly real place in which to dream.

The note left by the villagers on the church door always strikes a very sad chord with me: “Please treat our church and homes with care…”

…which, of course, sadly didn’t happen. Tyneham House itself, with it’s medieval hall, was soon robbed of its fittings and wainscoting before being shot to ribbons. Irrespective of where one falls in the argument that the requisition somehow “preserved” Tyneham in aspic, there’s no doubt that the villagers were fundamentally sold a lie when handing their homeland to the MoD. That simple act of sacrifice conjures up images of a generation now gone. Which seems so stark, as we live in a generation who – without getting political – will tolerate so little. I do find that emotionally arresting when listening back to the record.

Musically, how did you approach the album? Was it always going to be a very simple, acoustic recording, or did you consider any other approaches?

I think there was a mutual understanding that it would be a series of short musical vignettes – quick, atmospheric visits that would be heading out the door as soon as they arrived. That it should really feel like travelling through an unknown village, whilst heading onward to a larger destination. You get suggestions of things: a cat at the window, the village pump, the light from a bedroom window as someone finishes the day’s diary entry. But then it’s all gone before you get any names, faces or specifics. Thankyou for driving carefully.

And I guess, within the music, you tried to convey the sadness of villagers who never got to return to their homes?

That’s the thing about attempting to make an atmosphere rather than make a specific genre of music. It becomes more about how it’s interpreted by the person listening, rather than the intentions of those that created it. I’ve seen other people talk about an underlying sadness to the album, but for me it’s the most consciously joyful project I’ve ever worked on.

Frances Castle, from Clay Pipe, once told me the music was also partly inspired by the soundtracks to Children’s Film Foundation films. Is that true? Any CFF films in particular?

God… Soapbox Derby, Mr Horatio Knibbles… and the one where the kids build a hovercraft with a strange old man. Also the Look and Read series – basically anything with Wordy flying about with his sultry, stockinged arms. Things suggestive of a summer holiday, a tract of leafy countryside and a bike to get yourself around on. One of the most successful visuals that kept popping into my head was Five Go Mad in Dorset, despite being a satire. It really does capture a vibe.

I have a pet theory that connects slightly to the Tyneham House album. Basically I think, in Britain, the psychic trauma of World War 2 lingered well into the 1970s, even 1980s. Children’s entertainment in particular is riddled with references to “the war”. Plenty of CFF films have a wartime setting, but there were also books and TV shows like Carrie’s War and The Machine Gunners. Is this something that resonates with you?

Completely, and also the notion of a greater duty and sacrifice which – even when ill-advised – was incredibly admirable. It’s odd watching these forms of media become curate’s eggs in real-time, as we move farther away from those principles. Maybe it’s called getting old.

Did you grow up anywhere with Tyneham-style relics from World War 2 around you? I remember being shown pillboxes as a child, and being simultaneously fascinated and frightened by them. They made World War 2 somehow feel closer to the present day than I would have liked…

I did and still do. Back then I’d obsess over the online pillbox database to find them and make field recordings, which obviously now seems peak hauntology wanker. But it had an innocence to it back then, when I was first reading about the Stone Tape theory, etc. Over time I began thinking of pillboxes less as “liminal portals” and more as used Rubber Johnny repositories.

But there’s definitely a syntactical connection between their imposing Bauhaus-structures, with slits for eyes, and Tom Baker reading The Iron Man on Jackanory – which ranks as the most terrifying thing I experienced in childhood.

Opinion now seems to be divided about Tyneham itself – national embarrassment versus national treasure. Where do you stand?

I feel the fact that the military felt the need to grow a copse around the bullet-scarred remains of what was one of the finest houses in Dorset, whilst informing the public that it no longer existed, tells you all you need to know. It’s probably important to point out that whilst World War 2 looms large over Tyneham, that’s not what we were trying to get a sense of on the album. It was more the time before the guns came. The ordinary lives that people led, throwing rocks into the big pond and grazing sheep in the rectory garden.

Something that’s always fascinated me: some versions of Tyneham House include two “found” tracks… ‘A School Holiday (1977)’ and ‘May Day (1981)’. Where did these come from? Have you any idea where they were recorded, or who the people on them actually are? The lady running the kids through a piano recital fascinates me! I can quote her pretty much word for word. Ditto the bloke talking about the beauty of potatoes.

They are collages made up of cassettes recorded by the people you are hearing during those periods. We had less involvement in them than you’d probably expect.

I assume these recordings have no connection to Tyneham itself – but did you include them because you felt they somehow epitomised the spirit of the place?

None of the main album was physically recorded in Tyneham, although you may hear snippets of that on the cassette or accompanying download. But yes, they are intrinsically connected to the place – in a way you can only be when you are divorced from it. If that makes sense. A heightened notion of what Tyneham is and was, through romantic daydreams and notions.

From the start, the album has remained an anonymous creation. Why?

I can’t remember where exactly the idea came from to release it anonymously, but I think in part it was just the idea that it would be nice to have something that could exist outside the context of “these are the people who made it”. You could have the thing, and take it on its own terms. It just seemed unimportant really, who we were. That being said, I can’t pretend I don’t love a good mystery, and I think we both loved the idea that years after we made it someone might find an old battered copy in the back of a charity shop and wonder what it was all about. I always love when I discover a book, a painting or whatever and there’s very little information about it out there, so you just sort of speculate about who was behind it and why. That’s always going to be more interesting than the reality isn’t it?

When I think of the musical touchstones that informed the album – Virginia Astley’s From Gardens Where We Feel Secure or Felt’s Let The Snakes Crinkle Their Heads To Death – there’s no danger of those artist showing up and ruining the magic, is there? They’re little snapshots in time that don’t need a potted biography. Or to be dragged from one poorly mic-ed venue to the next on an ugly promotional treadmill. We’ve no ambition to repeat the trick with diminishing returns. Any notions of a “band” or personal ego seems vaguely ridiculous when all we wanted were street names and map locations, rather than who played bass on Track 3. All that needless minutiae subtracts from the feeling you’re trying to create, and – in my opinion – a lot of music could do without it.

Clay Pipe releases are always a lovely marriage of music and artwork – it must be nice to work with someone like Frances, whose sleeves complement the albums so beautifully?

Handing anything over to Frances is an easy decision because such care is taken. Aesthetically, she gets it spot on every time. It’s nice and uncommon as a musician to just say “there you go” and not have to worry about how the results will turn out. With this album and that label in particular, it was always going to be a marriage made in heaven.

It’s a gorgeous album that you should be so proud of. I discovered it in 2013, and it genuinely helped me through what was quite a difficult time with anxiety and depression. I listened to Tyneham House and Cate Brooks’ Shapwick on a loop that summer while walking through the local woods and fields, and now think of both albums as being an integral part of my recovery. Have you heard similar sentiments from anyone else?

I’m really pleased to hear that. I have albums that have performed a similar magic trick for me – and still do – and Tyneham House being a collaborative venture means I’m also removed enough to enjoy it objectively. That’s quite rare I think. It feels like it exists outside of myself, and it always has.

Tyneham House is available here:

https://claypipemusic.greedbag.com/buy/tyneham-house-0

Find out more about Tyneham here:

https://tynehamvillage.org/tyneham-village

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen

Yes, I’ve recently and repeatedly been watching the little ‘Bletchingley’ film. It makes me feel a bit funny in a good way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My headmaster was an Officer in the Second World War and he would sometimes mention it in school assembly. As is to be expected from teenage boys who had seen Monty Python, Ripping Yarns and Blackadder it was hard to resist making fun of him and sending him up. Just like we did with our French and German teachers who we called Old Worzel and Adolf respectively. The latter was even greeted with a fitting Hitler Salute. Behind his back.

When teacher or headmaster entered the classroom or the school hall we all had to stand up out of “our” respect. But you could hear whispered “I was in the war you know” in a mock Officer voice whenever the headmaster entered. “Yes, sir, The Boer War,” was the witty standard reply. We did this knowing that friends of the headmaster had died in the war and hadn’t come back. On other occasions boys would be invited into his study for tea and cakes so he could learn more about us and our studies. He must have liked me as I was invited three times. Though I imagine this was more to do with the fact that I had sung solo in the Cathedral choir. Yet it was another opportunity to mock him especially his choice of suit, hair and chinaware. As a boy I always regarded it as a great honour and privilege to greet or meet the headmaster. It was like meeting God with the same level of guilt. About the way we made fun of him.

It was only when I became a cadet myself that I began to realise and appreciate what previous generations had done for us. All that they had given up and sacrificed. My head was a part of this and very much helped to pass on to me this deeper sense of what was given and done – long before we were all born. This deeper sense of “a greater duty and sacrifice”. When our head retired I wrote to him to say thank you for all he had done. For all his encouragement, his leadership, his guidance. His profound Christian Faith born of struggle, sacrifice, sadness which he sought to pass on to us. He was this great influence on me. More than I realised when I was a boy. Imbuing a sense of respect and gratitude which we express in our own service, duty and lives today. Good night sir. I’ll never forget you along with the generations of boys you shaped, guided and influenced. Thank you.

LikeLike