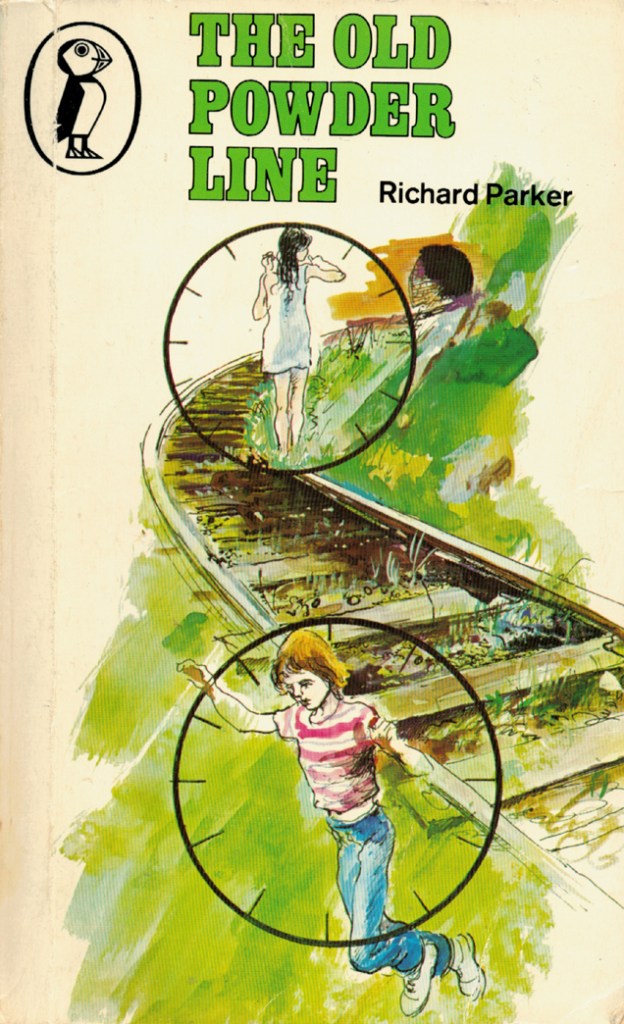

The greatest influence on The Old Powder Line, an endearingly modest tale of smalltown time travel? You could make a strong case for Philippa Pearce and Tom’s Midnight Garden; you could even – at a push – suggest John Masefield’s cautionary fable, The Box Of Delights. But I’m also pondering the unlikely inspiration provided by Dr Richard Beeching, chairman of British Railways from 1961-1965. While not exactly a literary classic, his government-commissioned 1963 report The Reshaping of British Railways led to the closure of thousands of miles of sleepy branch lines, instantly affording a yearning, spectral quality to the rusting tracks and deserted platforms suddenly lying neglected on the outskirts of isolated villages.

The simultaneous rise of the diesel engine lent a similarly romantic sense of instant nostalgia to the rapidly-disappearing steam train, too. Steam locomotives – already a staple of so many classic stories for children, including The Box of Delights – suddenly felt like instruments of time travel in their own right, transporting protaganists to a vanishing, semi-romanticised Britain steeped in a sense of leisurely enchantment. The Old Powder Line – written as Beeching’s recommended closures were in their final, devastating phase – expands the idea of steam-powered time-travel to an alluring conclusion. What if a magically resurrected steam train allowed us to make return journey day-trips to our own half-remembered childhoods?

The conceit is discovered accidentally by Brian Kane, a bored 15-year-old in self-imposed afternoon exile from a family home temporarily taken over by his older sister Julie and her wine-sipping friends. Notepad in hand, he intends to indulge in some idle trainspotting at his local station… a pastime that takes an unexpected turn when an unfamiliar porter directs him to the seemingly non-existent Platform Four, and a “steam train due in ten minutes”. Dismissing this, Brian idly explores the dank subway (“smelling of fungus and urine”) beneath the station’s twin lines, but quickly finds – to his surprise – a secret tunnel leading to the mysterious Platform Four itself and the Old Powder Line of the title: a long-abandoned branch line to a forgotten Victorian gunpowder factory, inexplicably now home to a fully-functioning steam service that appears to operate outside of linear time.

Boarding the train at the request of a mysterious fellow passenger (a boy who, it is implied, is himself a time-traveller from the near future) he seems to travel briefly along the line before arriving – inexplicably – back at the same station. But the timeslip has been activated. In an affecting sequence, Brian returns home, to the house that also doubles as a surgery for his doctor father, and finds – to his understandable disquiet – that stern-faced receptionist Miss Mincing fails to recognise him. Not only that, the bedrooms belonging to both him and his sister are now empty and lifeless. In the garden, he meets a younger version of his mother with a months-old baby boy… a baby, he comes to realise, that is his own infant self. That inexplicable steam train, puffing out magic and disquiet in equal measure, has transported Brian back to the mid-1950s and his own early childhood.

It’s not a permanent move. Racked with terror, Brian races back to the station and manages to leap aboard the same steam train, already beginning to chuff heartily on the return journey to 1971. Back in his own time, his familiar home life seems reassuringly unchanged: his sister and her bohemian chums (including one who, gloriously, “always smelled faintly of custard”) have polished off the afternoon’s wine and one of them – the willowy Wendy – is preparing to walk home across the modern-day remains of the Old Powder Line. Overcome by the first, post-traumatic rumblings of teenage romance, Brian nervously requests to accompany her, quickly spilling out the whole, strange story. Her gentle understanding and interest in his bizarre experiences become the genesis of a genuinely heartwarming double act that acts as much-needed grounding when the time-travel shenanigans become decidedly more complicated.

Which is the book’s main downfall: if anything, they’re rather too complicated. The trains on the Old Powder Line, it transpires, cross a “frontier” unique to every time-traveller, and journeying beyond this point (something strictly advised against by the gangly young porter, now mysteriously transformed into the train’s acerbic guard) will transport particularly determined passengers back beyond the point of their own birth. Here, they are likely to find their consciousness trapped inside the body of any passing time-traveller who was alive during this period: a conceit that sees Brian, now enmeshed in a web of wanton time tourism, viewing the 1920s version of his home town through the eyes of Miss Mincing’s middle-aged brother, Arnold. Who is himself using the Old Powder Line to revisit an idyllic childhood of poop-poop cars and afternoon matinees (“We’d just seen a film called The Mark of Zorro“) as an escape from a 1970s adulthood spent confined to a wheelchair. In addition, it seems, the intrepid time-travellers don’t arrive entirely intact in their own pasts. While Arnold Mincing is reliving the trappings of his own carefree youth, his fiftysomething body is discovered, pallid and comatose, lying on the modern-day version of the deserted railway platform from which he embarked on a journey increasingly fraught with danger.

For this simple-minded reader at least, it all becomes a bit too tangled. And it’s not difficult to imagine Richard Parker himself slumped over a six-foot flowchart of plot points, sweating profusely over the mechanics of his own time-travel theories and wondering how the hell to write himself out of a labyrinthine story that drifts just a little too far from its own charmingly straightforward premise. But there is charm in spades here: in Brian and Wendy’s burgeoning romance (reinforced when Wendy herself becomes trapped and endangered in the distant past), in the deceptively alluring depictions of that perfect, pre-war idyll, and – indeed – in Parker’s clear underlying message: that the constant temptation to mythologise our own childhoods is riddled with jeopardy. At the very least, it can distract us from enjoying the pleasures of the present day. As Arnold Mincing himself puts it: “Why are we all so obsessed with the past? It’s rather as if an explorer on the edge of an unknown jungle were to walk backwards, fascinated by his own footprints”.

With this in mind, I henceforth resign from the entire Haunted Generation project with immediate effect*.

POINT OF ORDER: Richard Parker was born in 1915, so are Arnold Mincing’s memories of 1920s rural England, of sadler’s shops and wild swimming in the local gravel pit, his own childhood reminiscences? They’re so vividly detailed that it’s hard not to speculate.

MUSTINESS REPORT: 7/10. My paperback copy of this book was bought from a Harrogate charity shop in March 2023 and – in July 1977 at least – belonged to a girl called Sarah Clark. Who presumably drew this splendid picture of what appears to be a rather happy snowman with little spindly legs.

*Not really. There’ll be another entry on Friday.

Help support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen

Truly, it’s a wonder we ever left the house as children…

LikeLike

love the drawing on the back…cover is interesting too

LikeLike

just finished the book myself and I love your follow up article 🙂

LikeLike