(First published in Electronic Sound magazine #81, September 2021)

DAMMIT, JANET

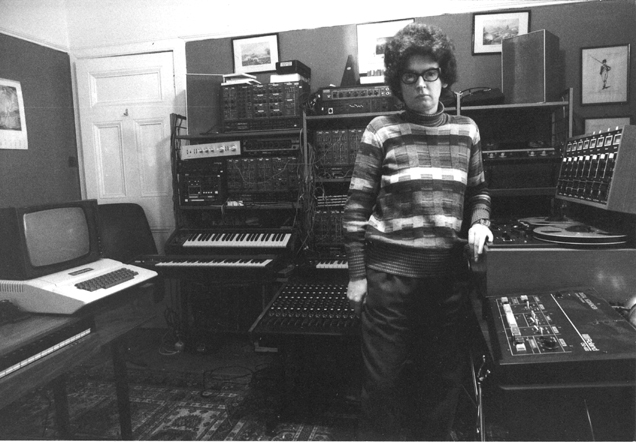

From wartime bombings to the creaking of tree bark, Janet Beat has always been fascinated by sound. Now 83, this contemporary of Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire is finally being recognised by her pioneering work, with the first collection of her electronic compositions released by Trunk Records

Words: Bob Fischer

“Although I lived in the countryside, we had three bombs fall on our little road,” remembers Janet Beat, with softly-spoken stoicism. “One of them fell onto a neighbour’s house while I was in it. I only lived to tell the tale because it didn’t explode – it just landed. But I remember hearing it come down. They spin, and there’s a screaming noise. And just before they land, because of the way sound travels, there’s a silence. We were taught – if we were outside – to throw ourselves to the ground at that moment.

“I heard it crash through the roof, and I was told later in life it was an incendiary bomb, so we wouldn’t have survived. The heat generated just sears the lungs. But I remember not being afraid, just being fascinated… until I heard the adults start to scream.”

Janet Beat is genuinely extraordinary. Born in 1937 and raised in rural Staffordshire, her hair-raising wartime memories alone from part of an essential social history. But they’re just a small fraction of a lifetime almost defined by her overpowering sense of curiosity. Crucially, her abiding fascination with the nature of sound led her to become one of Britain’s first – and perhaps most unjustly unrecognised – pioneers of electronic music. A contemporary of both Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire, she’s had to wait until her 84th year for the first commercial release of her collected electronic works.

“I was always very sensitive to sound,” she recalls. “I spent a lot of time on my own, and I used to put my ears to the bark of trees. If it was windy, you could hear them creaking deliciously. The rest of the scientific world have caught up now – they’ve got microphones, and can hear trees drawing up their water! I did that as a child, I just didn’t have the microphones.

“There was a big rhododendron bush that was hollow in the centre, and I used to crawl in there and listen to the sounds of nature. Rabbits thumping and seed pods bursting. And I noticed that different leaves make different sounds, according to whether they have a serrated or a smooth edge. Some make pink noise, some make white noise… I can still hear the difference.”

Her interest in composition began with a tune written on a toy piano at the age of three. Three years later, she overheard her mother suggesting the infant Janet might benefit from a spell in a children’s home “where the nuns will knock the music out of her”. Undeterred, her obsession was further fuelled by the BBC’s post-war radio output.

“There were only two radio stations: the Home Service and the Light Programme,” she remembers. “My mother and I used to search them for classical music. On the radio dial, it said things like ‘Moscow – Oslo – Hilversum – Luxembourg’. The reception was very distorted… sometimes it emphasised the upper frequencies, sometimes other radio stations butted in. That taught me about sound collage.”

Studying for a music degree at Birmingham University in the mid-1950s, her musical passions began to assume more esoteric leanings.

“I became interested in electronic music when I was a student, and I went to a shop that sold second-hand records,” she continues. “I picked up an LP of work by Pierre Henry. And I thought, ‘What is this?’. So with the money from my 21st birthday in 1958, I bought a Brenell Mark 5 tape machine. It was mono, and had an interchangeable capstan for very slow speeds. That was great – and with the mono track being in the middle of the tape, you could play it backwards, too. Later, I did tape loops.”

Where on Earth, I ponder, did that practical expertise come from? Those are pretty unorthodox interests for 1950s Staffordshire.

“There were books that came out by electronic engineers, so I learned about tape loops from those,” she explains. “I was only the ninth person in the UK to make music concrète. There was Daphne Oram and me… and some men! And some of them stopped because they were just ridiculed. But I bought a Tandberg stereo machine, which meant I could start to multi-track. And I also took a correspondence course in electronics, and built an oscilloscope! It was like painting by numbers to start with. And then I got into Elektronische Musik, because I bought the 10” LP of Stockhausen’s Gesang Der Jünglinge.

Accepting a teaching post at Worcester College of Education, she found an unlikely 1960s champion for her interests – a man now widely recognised as one of the 20th century’s leading experts on church and Early music.

“My head of department was the musicologist, Watkins Shaw,” she says. “We had long talks, and he was the one who encouraged me. We bought our own little studio oscilloscope, and the physics department were delighted that a woman was taking an interest in science! Their technician built a ring modulator for me, and a low-pass and high-pass filter, and I introduced a course on electronic music to the students.

“But everywhere else I’ve been, I’ve had opposition from heads of departments.”

Fired by the experience of seeing Wendy Carlos performing on TV in the early 1970s, Janet spent a year marking Open University coursework to earn the money to buy her first synthesizer.

“The EMS Synthi A!” she exclaims. “In suitcase form. Watkins Shaw came with me, and we went to Putney, to Peter Zinovieff’s place. God, he was arrogant. He wasn’t certain whether he was going to sell one of his synths to me, because I was ‘provincial’. And I mentioned Daphne Oram – that was a red rag to a bull. He couldn’t stand her!

“The prices were going up all the time, but his secretary said ‘This is Friday, and the price doesn’t go up until Monday… I’ll sell you it at today’s price’.”

In 1972, she joined the full-time teaching staff at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (RSMAD), founding another electronic studio. Here, she finally encountered her musical kindred spirit.

“I met Daphne in the 1970s when she wrote her book,” she recalls. “The director of studies at the RSAMD was a chap who’d been a BBC producer, and he invited her up to give a talk. He took me to lunch with her, and she was thrilled to find another woman interested in technology. She invited me to visit her, at Tower Folly. It was a converted oast house, and she had her studio in a garden shed. She was delightful, and told me about various suppliers I could visit to build my own circuits.”

Electronic music is far from the sum-total of Janet Beat’s lifetime of work. In the 1960s, she worked as an orchestral horn player until her technique was limited by a serious mouth operation (“I was told I would never play again – stop trying to be like a man, go away and have babies”), and her electronic experiments have always gone hand-in-hand with a prolific body of classical compositions. In 1980 she was a founder of the Scottish Society of Composers, and in 1992 she became visiting composer at Hochschule für Musik Nürnberg, the respected German conservatoire. She sees no great divide between the two contrasting disciplines.

“They seem like two sides of the same coin, because I’m a person full of curiosity,” she insists. “The world is a wonderful place to live in. I still look under stones to see what’s underneath them.”

Inevitably, this insatiable curiosity found its way into her teaching practices. “When I started the electronic music and recording studio at the RSAMD, I’d tell the students about harmonics and get them to miaow like a cat,” she chuckles. “Because when a cat goes ‘miaow’ it’s acting like a bandpass filter! So I’d say ‘Sing on a note to suit your voice, and miaow – and you should be able to hear the sine waves inside your head’.

“The rest of the staff always knew what time of year it was, when the students went into the refectory miaowing…”

Perhaps equally predictably, this unorthodox approach also brought her into conflict with the more traditionally-minded patricians of 1970s and ‘80s academia. “I lived through three different principals, and ten different heads of department, and only one was helpful,” she sighs. “At times I was told to stop composing. They increased my teaching hours to try and stop me. I said ‘You cannot tell me what to do in my leisure time’.”

“Somebody said to me once, ‘I bet you’re pleased about the Sex Discrimination Act’. I said ‘In one way yes, but in another it just makes the misogyny go underground’. I like to know where it’s coming from, so I can be prepared for it.”

In 1981, her shimmering, 10-minute ambient track ‘Dancing On Moonbeams’ was included on a compilation entitled Music By Scottish Composers Volume One. For 40 years, it remained the only commercial release of any of her electronic compositions.

“I’d bought some more units for my Roland 100M synthesizer,” she remembers, gleefully. “In fact, with the various keyboards I had, I was able to run 16 oscillators together, like A Clockwork Orange!

“But I made the mistake of writing-a-tongue in cheek sleeve note for it. Never do that, because it was taken seriously by the critics. ‘Close your eyes and become an aural astronaut…’ The other composers on the disc had written very serious notes about their music and I thought mine was a bit of fun. Big mistake…”

‘Dancing On Moonbeams’ is the opening track on Trunk’s new collection, the mischievously-titled Janet Beat: Pioneering Knob Twiddler. Also included are two modular 1983 pieces produced for Channel 4 to accompany director Eddie McConnell’s atmospheric Second Glance: Lighthouse film. Presented with a wordless documentary following the daily travails of these lonely maritime outposts, she approached the task with typical irreverence.

“He was a great film-maker but had cloth ears when it came to music,” she laughs. “He’d say ‘Can you make a wee tune with three notes, like the wind blowing telegraph wires? Can you make me a tune like singing voices drowning?’”

Elsewhere, there is 1987’s ‘Echoes from Bali’ – a hypnotic Yamaha DX7 recreation of Indonesian Gamelan music.

“When I was a schoolgirl, there was a History of Music and Sound 78 RPM record of a Gamelan orchestra,” she recalls. “I was fascinated by it, particularly the tuning of the metal bars of their instruments to be – to Western ears – slightly out of tune. You get a shimmering effect. That made me want to go to Java to hear the real thing.”

It was an ambition she fulfilled decades later.

“I chose a tourist holiday, but stayed behind to play Javanese-style Gamelan,” she remembers. “It’s very beautiful, and the dancing is incredible. The devils and the demons and the monkey characters move so rapidly. In fact, the monkey gambolled and landed with his head in my lap. And said, under his mask, ‘Sorry’. But when he made his next entry, he was eyeing me up, and I thought ‘He’s going to do it again…’.

He did, and this time he whispered ‘Nice…’”

Although she continues to compose in the classical idiom, her electronic work ended over a decade ago, with the sale of her ailing studio. Many of her earliest compositions, she admits wistfully, are also lost forever.

“A lot of my old tapes are missing,” she confesses. “My father actually used some of them to tie things up in the kitchen and garden. I don’t think he did it deliberately to destroy my music, but he was a great recycler. I came home once and found his raspberry canes tied together with my tapes. So I lost everything.We had a blazing row. But the tapes still performed, because they acted like a wind chime. The Brenell Mark 5 weighed a ton, so I couldn’t have dragged it into the garden. But if I had, I would have written a piece called ‘Phoenix’.”

You might be forgiven for assuming a fractious relationship with her parents, but there’s a heartrending sting in the tale. As we wind up our conversation, she tells me about ‘Aztec Myth’, a 1987 composition for voice and tape. She intends the anecdote as an example of her multi-faceted thought processes, but it becomes something else entirely.

“I remembered reading an extract from an Aztec poem,” she recalls. “But it wasn’t long enough for what I wanted. So this is where my curiosity comes in. I heard that a scientist was considering whether viruses were once part of our DNA. I also heard that, in trying to help people with brain damage, scientists were experimenting with enzymes. And also… my mother died of myeloid leukemia. Which, in the 1970s, was a death sentence. So I put all these elements together.”

She recites the lyrics down the phone:

“Your enzymes changed my brain cells, then my pulsing heart came verdant. Greener than the springtime grass, I put forth crimson flowers. But oh, alas, like the rosebush I flowered and withered…”

At which point she breaks off, clearly emotional.

“Sorry,” she apologises, entirely unnecessarily. “I’m getting upset because it reminds me of my mother. Don’t worry, I’ll get over it…”

And that soft-spoken stoicism swiftly returns. She finishes the recitation, undaunted. It’s been almost two hours since the conversation started, but an afternoon with Janet Beat has proved both an education and a privilege. We sign off in upbeat mood.

“I’ve come back into fashion – I’m having a renaissance!” she chuckles, as we say goodbye. “Normally that happens just after you’ve died, so I’m quite enjoying being here to appreciate it…”

Janet Beat: Pioneering Knob Twiddler is available here:

https://trunkrecords.greedbag.com/buy/pioneering-knob-twiddler/

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” –is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen