(This article first published in the Fortean Times No 403, dated March 2021)

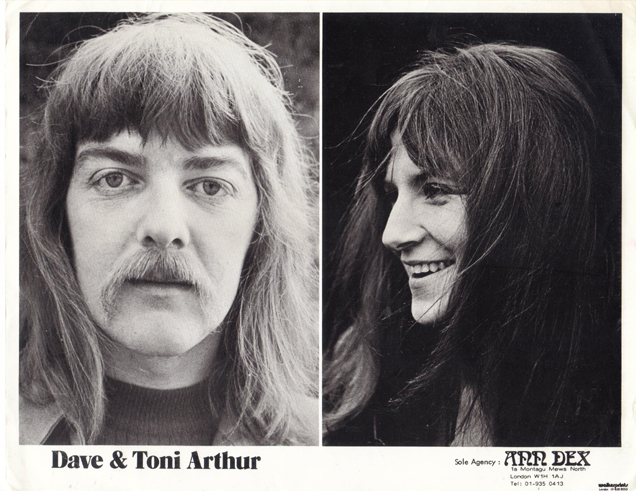

In 1970, Dave and Toni Arthur recorded Hearken to the Witches Rune, an occult-themed LP of traditional British folk songs. Fifty years on, the album has gained cult status. But the record’s gestation and legacy is just as extraordinary as the music itself: a story that stretches from the basement rituals of tabloid-baiting “King of the Witches” Alex Sanders to children’s TV favourites Play School and Play Away. Dave and Toni reminisce with Bob Fischer

“I was interested in magic and witchcraft and things like that from an early age,” says Dave Arthur. “Twelve or so. Dennis Wheatley‘s novels… I read those. The Devil Rides Out, To the Devil a Daughter, The Ka of Gifford Hillary. Occult novels fascinated me when I was a kid. And then I discovered the Atlantis Bookshop, just by the British Museum, which was the occult bookshop in London at the time. All the magicians and occultists of the time used to hang out there, and I was part of that scene. It was one of those old-fashioned bookshops, with piles of books all over the floor, all dusty and dark.”

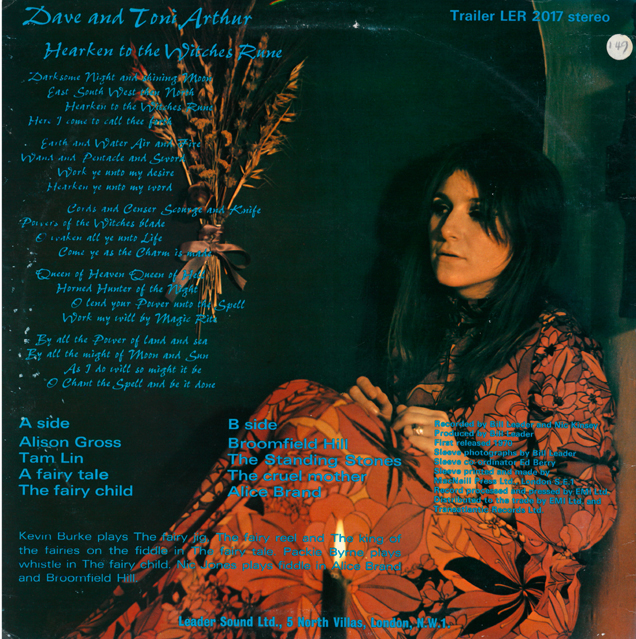

We’re discussing the background to Hearken to the Witches Rune, an album of starkly beautiful folk music recorded by Dave and his then-wife Toni in 1970. Fifty years on, it’s an LP that maintains a devoted cult following among enthusiasts of folklore, occultism and esoteric music alike. Its eight tracks are riddled with tales of fairies, shapeshifting, spells and Elfin Queens, all performed into a Revox A77 reel-to-reel tape recorder in a first-floor Camden Town flat. Its subsequent scarcity has only compounded the record’s mystique: it has been resolutely unavailable since the 1970s. There is no pristine digital remaster, no CD box set or deluxe 21st century vinyl, and abandon hope all ye seeking iTunes downloads or Spotify streams. The vintage crackles of increasingly elusive eBay copies and DIY Youtube rips have themselves become part of the album’s own extraordinary story.

“I had totally forgotten his absolute predilection for Dennis Wheatley!” exclaims Toni. I speak with them both, one after the other on the same afternoon, via crackling Skype connections at the height of Covid-19 lockdown. Both are fast-talking, funny and fascinating conversationalists. I’m keen to discover where this mutual interest in the supernatural arose, and what part – if any – the genuinely uncanny played in their respective upbringings.

“I’ve had a lot of strange experiences,” continues Toni. “A lot of stuff that could be construed as magic. When Dave and I got together, I’d had a very ordinary background, but I’d had some very extraordinary things happen. I’ll give you one instance: I had my first piano lesson when I was nine. Mum took me round to see Miss Adams… she was my schoolteacher, but she also taught music. I went there, and had my first lesson.

“And I got to school the next day, and in those days every classroom had a piano in it. Miss Adams said ‘Now, Antoinette had her first lesson yesterday. And what did you learn? Come to the piano, and you can play it.’ And it was a tiny, five-note little thing. I said ‘That’s what we did… and I’m going to do another thing later, and another thing later, and at the end I’m going to play this…’

“And then I played the last piece in the book, reading from the music.”

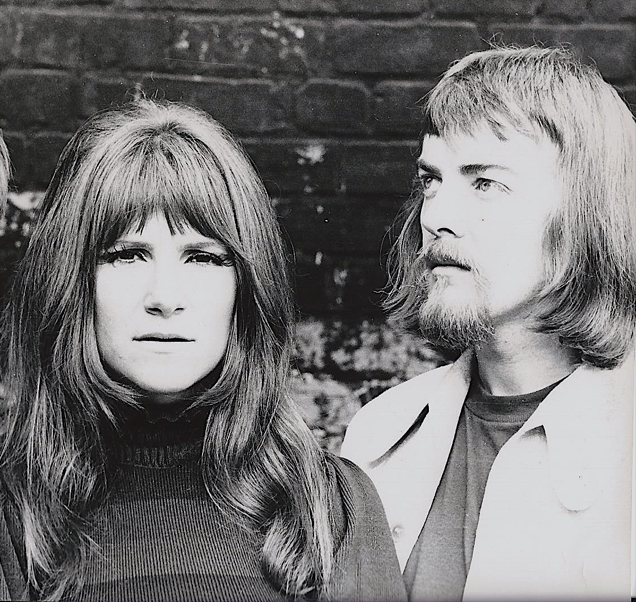

Dave Arthur was born in Cheshire and Antoinette Wilson (“We’ll gloss over that,” she laughs) in Oxford, but both moved to London at an early age. At the turn of the 1960s, the pair met as teenagers at The Twelve Stringer, a late-night coffee bar run by Dave. Toni, then a nurse at University College Hospital, was brought along one night by her flatmate, the promising blues guitarist Buddy Watson.

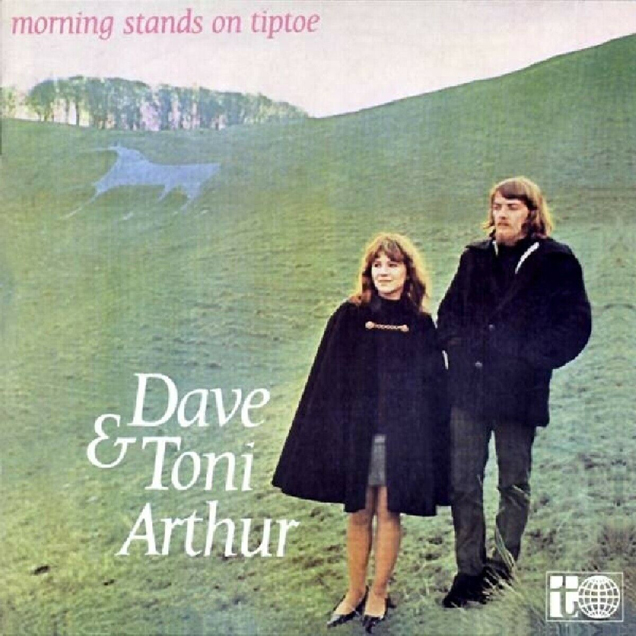

They married in 1963, moving to Oxford to run a university bookshop while simultaneously building a reputation on the folk club circuit. Their 7” version of traditional folk song ‘The Cuckoo’, recorded as The Strollers, was released on the Fontana label in 1965. Its crossover folk-pop stylings, however, were absent from the minimalist albums that followed: Morning Stands on Tiptoe (1967) and The Lark in the Morning (1969). Both are beautiful essays in unaccompanied traditional song with a distinct leaning towards the pastoral. As the decade wore on, the Arthurs’ interests progressed from interpreting established folk club favourites to actively seeking out hitherto uncelebrated stories and songs – with an increasing leaning towards the uncanny.

“And everywhere we went, we would be tracking people down and interviewing them. Going out to the countryside, to Travellers and canal barge people, fairground people, and – particularly – farmers. Talking to them and recording them.”

One folk tale collected in such a manner is alluded to on ‘Magic In Ballads’, a hand-typed four-page pamphlet included with the first pressing of Hearken to the Witches Rune. “In Norfolk a while ago,” it begins, “An old farmer told us about a horseman who sold his soul to the Devil…”

“He sold his soul and underwent the Toad Ritual,” says Dave, continuing the story fifty years on. “Finding a walking toad and burying it until the ants have eaten all the flesh, then throwing the bones into running water. This has to be renewed every seven years, but he didn’t manage it – he didn’t find a toad in time. And he went into the barn one morning to get his horse’s harness, and the whole thing just burst into flames. He died in the inferno.

“That was told to us by an old farmer in Norfolk as a true story. He said he knew the people it had happened to.”

“It’s like any form of mythology,” adds Toni. “People are frightened of their surroundings, so you get supernatural things coming out.”

This hands-on collection of oral tradition followed in the footsteps of singer and folklorist A.L. “Bert” Lloyd, whose 1950s crusade to document – and, indeed, perform – the vanishing folk tales and songs of the British aisles was clearly an inspiration to the youthful duo.

“We did an awful lot of research,” says Toni, now a Norfolk resident herself. “It was a passion, a complete passion. And there was no time when we went around the countryside that we didn’t stop at places and look at things. Markets used to be a big thing. I wore a beautiful horsebrass that represented the three stages of the moon… I’ve still got it on the beam of an Inglenook, near where I sit. It’s absolutely gorgeous, and supposedly the Queen of the Witches wore it. So I used to wear it round my neck… it’s actually pretty heavy!”

And, as detailed in ‘Magic In Ballads’, the duo’s interest in the secret rituals of the Norfolk horsemen led to conversations with Scottish folklorist Hamish Henderson, who had collected similar tales of The Horseman’s Word – “an anti-Calvinist farm workers guild, with smatterings of the occult”.“When we sang in Scotland, we’d spend time in Edinburgh with Hamish,” says Dave. “Drinking, most of the time – in his favourite malt whiskey bar. But talking about folklore and ballads, obviously. And we mentioned to him at some point about the Toad Men in Norfolk and the Horseman’s Word, and he sent us some information that he had.

“And then someone wrote to me out of the blue. Their grandfather had been in the Horseman’s Word, and they sent me pages and pages of transcripts… what he remembered of some of the songs he’d learnt at these convivial meetings. They used to get together, get hammered in the markets, and sing these songs about shagging Queen Victoria!

“So that was all going on at the time. We took bits from Hamish, bits from Bert Lloyd, bits that we’d come across, and we’d put versions of songs together that we felt told these stories to our satisfaction. That’s what we were doing at the time we met Alex Sanders.”

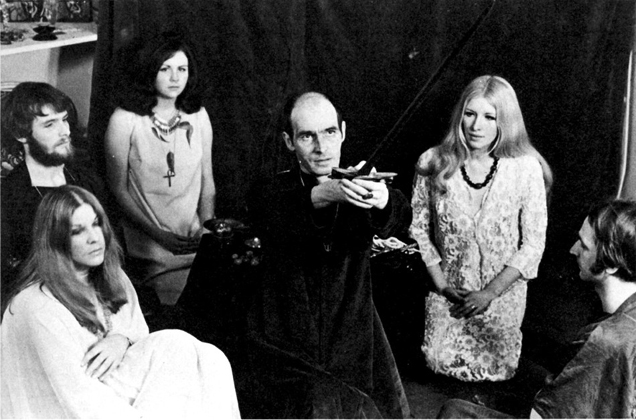

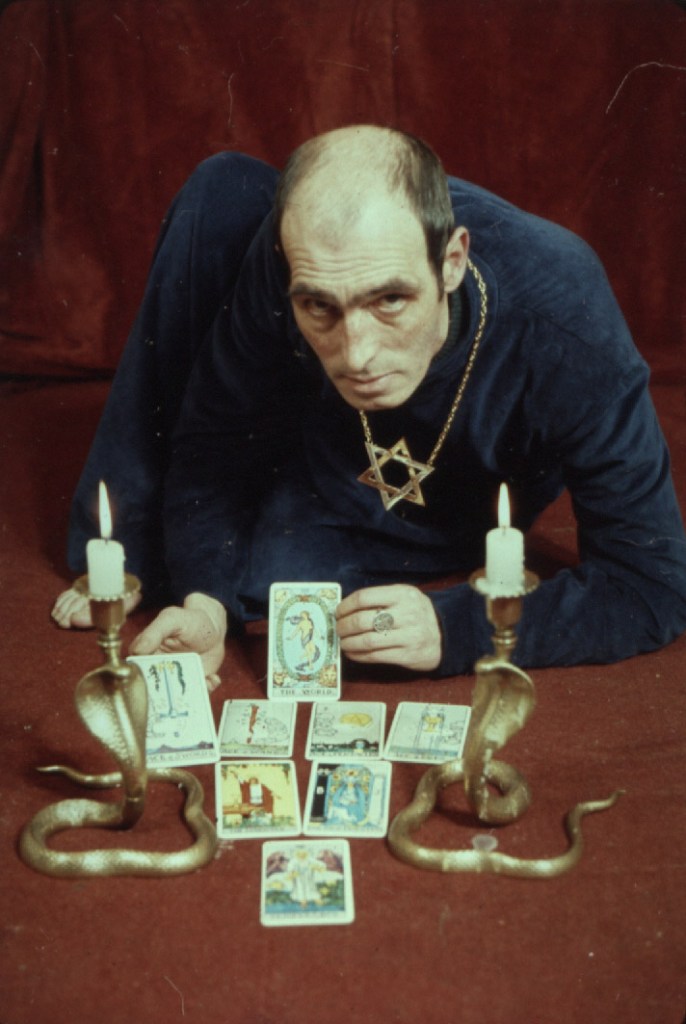

By the mid-1960s, Alex Sanders was already a high profile figure. The so-called “King of the Witches” was on the verge of transplanting his Wiccan coven from Manchester to fashionable West London, and was attracting national tabloid attention. “HORROR ‘WEDDING’ IN A WITCHES TEMPLE” was the headline of a full-page “expose” by Peter Forbes in The People, dated Sunday 5th December 1965. “Maxine Morris is blonde, slim and just 18,” wrote an outraged Forbes. “And on Wednesday, she will give herself to a man old enough to be her father.”

“She will become the bride of 39-year-old Alex Sanders in the name of witchcraft… black candles will burn on the witches’ altar. The air will be heavy with incense… and into this vile mockery of a wedding ceremony will step little Maxine, naked under a white wedding dress that Sanders has made for her.”

By the end of the decade, the Sanders’ notoriety as the first celebrity couple of 20th century Wicca had been cemented, their religion now enthusiastically practised from a basement flat in Notting Hill. In 1966, both Alex and Maxine had appeared as TV chat show guests of jazz saxophonist Benny Green on Rediffusion’s Late Show London, and a slew of media attention followed. By 1969, the Sanders’ profile was sufficient to warrant a biography: June Johns’ King of the Witches: The World of Alex Sanders was published by Pan Books. In January 1970, both Alex and Maxine were featured on BBC1 current affairs show 24 Hours and, in March, Alex was a studio guest on The Simon Dee Show, alongside – curiously – Dennis Wheatley.

“We’d heard about him,” says Dave. “We saw an interview on television or in a newspaper. He was notorious, a great self-publicist. We found out where he was and said we were interested in the background to these magical songs, and asked if he would talk to us about it. He was very generous, and we went to Clanricarde Gardens. He and Maxine had their temple in the basement, laid out with a huge pentacle on the floor.”

“We had an afternoon chatting to him, and he said ‘Are you interested in joining my group?’ And that was it, that was exactly what we wanted. We wanted to find out how much of Wicca, the modern witchcraft, was based on traditional stuff, and how much traditional material had been carried through in the form of ballads.”

“Most people at that time were really scared of that kind of thing,” says Toni. “Witchcraft still had such a bad name. But the more you researched it, you just found that it was another form of religion. A way of life. People confused witchcraft with black magic, and it just wasn’t that. The Wiccans we knew were working for the good of things.”

Both Dave and Toni are keen to emphasise Alex’s impish sense of mischief, a factor that may explain the Sanders coven’s rather outré public image.“He had a great sense of humour, actually,” says Dave. “He said ‘If you come along, you do realise it’s a sex orgy? It’s all naked, and we roll about all over, but if you want to know about Wicca then this is it. Come down next Tuesday night…’

“‘We said ‘Thanks ever so much, Alex,’ and went home. As much as we wanted to find out about it, we didn’t want to go rolling around naked and indulging in orgies! We rang him up and said ‘We’ll pass on the orgies if that’s OK…’ Our interest wasn’t anything to do with that, it was a serious study of narrative and folklore and the continuation of folklore ideas into modern witchcraft.

“And he said ‘That’s OK, I was just winding you up.’ He said it was a test and, had we agreed to visit in expectation of some sort of sexual event, he would have turned us away.”

Toni laughs. “He was a strange bugger, he really was!” she says, with clear affection. “He liked having a joke…”

And the other coven members? “They were all people that didn’t really fit into a lot of other places,” she remembers. “And yet they really belonged there. They were going there because they wanted to worship something. I remember at that time thinking of Spike Milligan – ‘Hello trees, hello world!’. They were really lovely. They weren’t ‘grand’, they were ordinary people.”

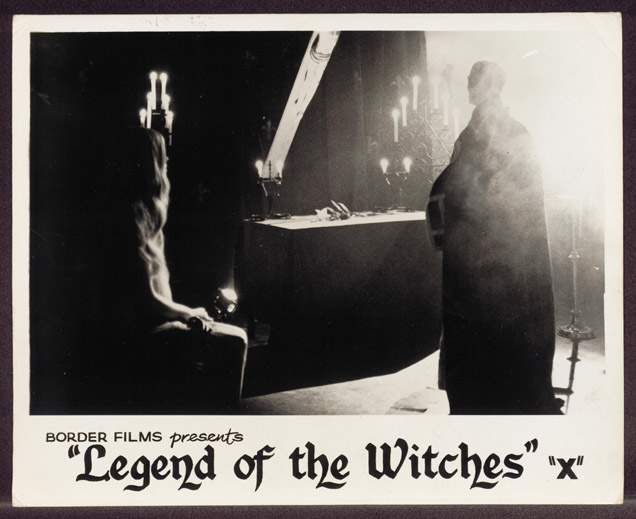

The activities of the Sanders coven during this period are immortalised in Malcolm Leigh’s documentary film Legend of the Witches, released into cinemas in February 1970. Swathed in psychedelic sitars and stroboscopic lights, it features Alex and Maxine conducting an array of occult rituals; their frequent state of undress doubtless responsible for much of the fevered media attention they attracted.

“There was nakedness, no doubt about that!” says Dave. “That wasn’t a problem, that didn’t bother us. What would have bothered us was it being some excuse for on orgy, which it wasn’t at all. It was a serious thing.

“Alex opened the circle up, and went round – North, South, East, West, all that – and called down the Gods. And then there’d usually be a ‘working’ for somebody who was ill. We’d all wish them well and tie knots – knot magic, cord magic – to try and help people. I was perfectly happy doing all of that, nothing bothered me.

“But the basic problem is that I’m non-religious. I’m an atheist. I don’t believe in any of that. I’m interested, but I wouldn’t go along with it as a belief. I don’t believe in any sort of god, let alone Old Gods. I’m interested from an academic point of view, but not from a practical, performing point of view.”

The Sanders coven, however, wasn’t the only esoteric meeting attended by the Arthurs. The Bricket Wood coven had been founded in Hertfordshire in the late 1940s by retired civil servant and 20th century Wiccan pioneer Gerald Gardner, and – by the late 1960s – counted accomplished studio engineer Dick Swettenham amongst its members. Swettenham had worked at Abbey Road and Olympic Studios and had become a director of Topic Records, the pioneering folk label that released The Lark in the Morning. His presence on the Wiccan scene might suggest that interest in the religion was becoming widespread in folk music circles, but the couple deny this.

“I think you may have found it all!” says Toni. “At that time, as far as we knew, it was just Dick Swettenham and us.”

Dave agrees. “Nobody knew about Dick Swettenham, he kept it quiet. He was a very respected sound engineer designing exotic desks for big companies, and at that time it wasn’t a thing you promoted. You certainly wouldn’t go out saying ‘I’m Dick Swettenham, I’m a designer of very expensive desks for Decca Records… and oh, by the way, I’m a witch!’

“We went up to the Gardnerian coven. Dick took us, because he knew we were interested in magic and witchcraft. We went to a couple of their meetings, in Gerald Gardner’s original Elizabethan cabin, and it was fascinating. But we found the people who took a less intellectual approach – to put it nicely – got more out of it, and felt more powerful, than the people who were merely intellectualising. You’d get farm or building labourers who had no intellectual pretensions, but had a deep feeling for things. They weren’t acting anything out – they believed in it wholeheartedly, and it seemed to work for them.”

Toni agrees. “It was very, very clever people saying: ‘This is a very clever bit, and now we’ve learned this and we’ve learned that, we’re going to do this and… oh my goodness, it doesn’t work’.

“Whereas with Alex’s place, the simplicity was almost tangible. You knew you were in a place where people were protecting you. It’s strange. I’m not Christian, I’m Buddhist. But if I needed to go to a church to worship in that way, I would look up to a priest like that.”

Both Dave and Toni are also keen to stress the altruistic side of the Sanders’ coven.

“Alex tried to do an awful lot of work for people with mental health troubles,” says Toni. “Especially when they thought they were hearing voices. He would say ‘But you’re so chosen, to hear those voices…’”

Dave concurs. “He would say ‘The thing to do is to control the voices: if they’re coming to you at inopportune moments, say: Come back, and we’ll talk later.’ It empowered them and really helped them. We saw people who were living quite happily in control, and the voices weren’t taking them over’.

Meanwhile, Toni was finding her interest in the otherworldly extending beyond the purely academic.

“It was Alex that taught me to read tarot cards,” she recalls. “He said to me one day ‘Look – you’re doing all this research, you can read the tarot.’ And I’d never heard the expression ‘tarot cards’ before. Not at all. But he said ‘I’ve got a brand new pack, and they must be yours – you must never let anybody else touch them. Keep shuffling them, and I’m going to show you a pattern you can lay them in. And I’m going to bring a lady down, and while you’re talking to her just assess everything about her then lay the cards out exactly as you think…’”

“So this lady came down, she was Greek. She was absolutely fabulous – a little tiny lady, full of joy. And I laid the cards out, and probably started with ‘I see you come from a foreign land…’ Which… hello! Was so obvious. But I was very worried about something that was coming up, something that the cards seemed to be telling me. And Alex said ‘You’ve missed out an obvious thing. Are you not interested in what she does for a living?’

“I said ‘No, no, I’m not…’

“He said ‘By the sound of your voice, you are… just tell her!’

“So I said ‘You’re a prostitute, aren’t you?’

“And she was!”

She qualifies this: “I thought I was intellectually interested, not spiritually. At that time I didn’t really think about the strange things that had happened to me earlier in my life, I just thought they were strange. I didn’t join the two up at the time. That came later.”

Although British folk tales and songs are riddled with tales of ancient witchcraft, the Arthurs concluded that the folk tradition had failed to permeate the texts and practices of 20th century Wicca. Nevertheless, they found entertaining ways to combine the two. “Toni and I sang ‘John Barleycorn’ to accompany a cod ritual Alex put together to satisfy the curiosity of a German film crew,” remembers Dave. “It involved tipping bags of flour over people, some business with corn dollies, and culminated with beer being poured over the heads of the celebrants. It was a very messy but quite spectacular ‘ritual’! But the German director loved it, and went away very happy…”

By 1970, the couple were ready to begin the sessions that would become Hearken to the Witches Rune, an album recorded in a manner that will gladden their hearts of locked-down, lo-fi 21st century musicians. With the couple’s favoured producer Bill Leader at the helm, the entire record was recorded on a reel-to-reel tape machine in the North London flat occupied by both Bill and his wife Helen.

“5 North Villas, Camden Town,” nods Dave. “Bill and Helen were up on the first floor. And the recording was done on a Revox A77 – in their bedroom, I think. We cleared a space out, and the bed was in the corner. There were records everywhere – the walls were covered in terrifyingly weighty 78s and Christ knows what else. If they’d have come down on someone, they’d have killed them.”

Endearingly, the room used for the recording sessions is the only point in the entire story where which Dave and Toni’s memories diverge.

“I didn’t know Bill Leader’s bedroom, I can assure you of that!” laughs Toni. “No, it was next door to the kitchen. There was a permanent screen with a door in it, dividing one half of the room from the other. One part of it was the sitting room, and the other was the kitchen. And we recorded everything in the sitting room area – which would quite often smell of onions if somebody had just been cooking.”

“You only had to walk in there and you sounded as though you were walking through an autumn forest,” she smiles. “There were piles of tape all over the floor…”

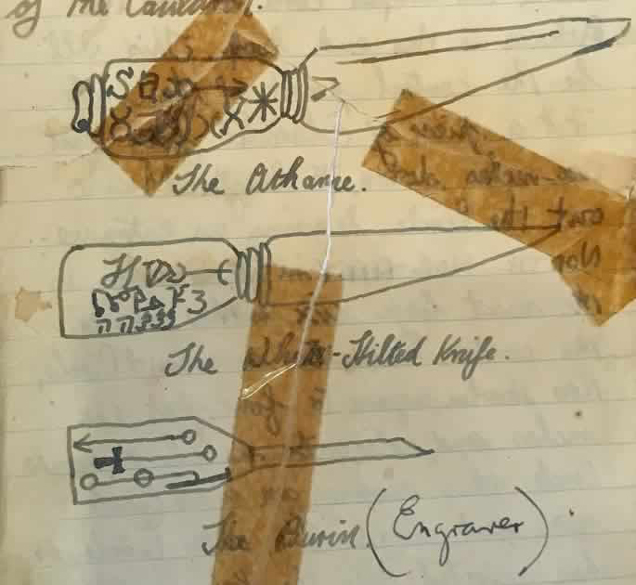

The album’s title is taken from the Book of Shadows, the Wiccan text originally compiled by Gerald Gardner and his High Priestess Doreen Valiente around the turn of the 1950s. Tradition dictates that coven members must create their own version of the book, copied out by hand – a task that Dave completed using Alex Sanders’ own hand-written copy as his source material. The phrase itself is included in ‘The Witch’s Chant’, a poem composed by Valiente:

Darksome night and shining Moon

Hell’s dark mistress Heaven’s Queen

Harken to the Witches’ Rune

Diana, Lilith, Melusine!

Although an alternate version exists, also written by Valiente and entitled ‘The Witches Rune’; and Sanders’ interpretation of the rhyme, as copied out by Dave and reproduced on the album’s back sleeve, has further variations. Dave is intrigued enough to mull over a full, future investigation. The front cover of the album, meanwhile, features the Arthurs looking suitably haunted, emerging from an all-pervading darkness in flowing, red robes. It was taken, Dave tells me, in the family garden – the ethereal lighting provided by the headlights of Bill Leader’s car.

Even the album’s release, on Leader’s own Trailer Records, is shrouded in some degree of mystery. The back sleeve boldly states “First released 1970”, but the label on the vinyl has a 1971 copyright notice. The autumn 1970 edition of the quarterly English Dance & Song magazine lists it as a forthcoming release, but didn’t review it until autumn 1971. Neither Dave nor Toni are entirely sure, and neither is Bill – now aged 91 and living in quiet retirement in Manchester. The internet, typically, is equally vague. Toni at least narrows down the date of the cover photo shoot: she remembers being heavily pregnant with the couple’s son Tim, born in September 1970.

Listening to Hearken to the Witches Rune in 2021 is just as startling as experience as it must have been in 1971. As with their previous albums, the Arthurs’ voices are often unaccompanied, although veteran Irish musician Packie Byrne adds tin whistle to ‘The Fairy Child’. Based on a poem by 19th century Dublin lyricist Samuel Lover, it’s a haunting mother’s lament for a child abducted by fairies. Young violinist Nic Jones contributes to ‘Broomfield Hill’ – the tale of a young maiden using magical powers to protect her virginity from the attention of a boastful knight – and also plays on ‘Alice Brand’, in which a runaway couple wage an occult battle against a vengeful Elfin King. And equally youthful fiddle-player Kevin Burke enjoys a tour-de-force performance on ‘A Fairy Tale’, a medley of three traditional Irish instrumentals introduced by Dave.

I ask both Dave and Toni to select their favourite tracks from the album.

“That lovely version of ‘A Fairy Child’, with Packie Byrne’s whistle on it,” says Dave. Toni’s got a great voice. That was one we didn’t change, we actually just took the poem and Packie played the whistle.”

Toni agrees. “‘The Fairy Child’, because of Packie Byrne,” she says. “I absolutely adored Packie, I can’t tell you… he was the nicest, loveliest man. He sat opposite me, looking like a fairy. He was quite old then, with pure white hair. We looked in each others eyes, with the microphones between us, and we just… well, if you listen to it – we don’t veer. We’re just going for the words and the meaning of the song.”

“And ‘The Standing Stones Ballad’,” continues Dave, “I love that. That’s one we didn’t change, because we felt it was the definitive version. We got that from John and Ethel Findlater, an old couple in the Orkneys… they sang in perfect unison, and their daughter played melodeon. It was a lovely track, from a field recording we heard.”

The lynchpin of the album is arguably ‘Tam Lin’. A traditional Scottish ballad dating back to at least the 16th century, its central figure Tam-a-Lin seeks release from his bondage to an Elfin Queen, and enlists the help of “Fair Margaret”, who vows to spring him from the Elfin court on Hallowe’en night. Despite the Queen’s best efforts, transforming Tam-a-Lin into both a wolf and an adder in his new lover’s arms, Margaret is successful. The Arthurs’ version was assembled from multiple sources: lyrics collected by Francis James Child in the 19th century, together with a melody uncovered by Hamish Henderson and given to Bert Lloyd to perform. Dave and Toni’s version, sung unaccompanied, is stark and potent.

It became an integral part of their live set, its magical properties apparent during a memorable early 1970s performance at Rochester Cathedral, where it seemed to elicit a violent thunderstorm.

“Oh God! I’ll never forget that!” exclaims Toni. I sang ‘Out then cried the Elfin Queen…’ and… BOOM! BOOM! FLASH! FLASH FLASH! I nearly wet myself, it was so terrifying. The whole audience went ‘Aaaaah!’ And the next line is ‘And an angry woman was she…’ God, it was really, really frightening.”

The duo also took Tam Lin into unexpected musical realms. For the sixth episode of Dave’s BBC Radio 3 series Arthur’s Folk, broadcast on Friday 1st July 1977, the couple enlisted the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Paddy Kingsland – later celebrated for his work on Doctor Who and The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – to help transform the ancient ballad into an electronic folk rock epic.

“We wanted to use the potential of folk rock,” explains Dave, “But why stop at that? Why not explore other potentials? Which, at that time, was Radiophonics. So we started off acoustic and unaccompanied, but we had a rock drummer and two session singers. Me on the guitar, Toni on recorder, and a classical keyboard. It slowly built up, then the electric band came in.

“And the end of the ballad was done over Doctor Who-type music, with swirling sounds creating an atmosphere.”

“We had a good quality copy,” says Toni, “But one of our children threw a party that we weren’t supposed to know about. And the reel-to-reel ended up in a pot that had a huge monstera plant in it. You know, the cheeseplants? And somebody peed all over it…”

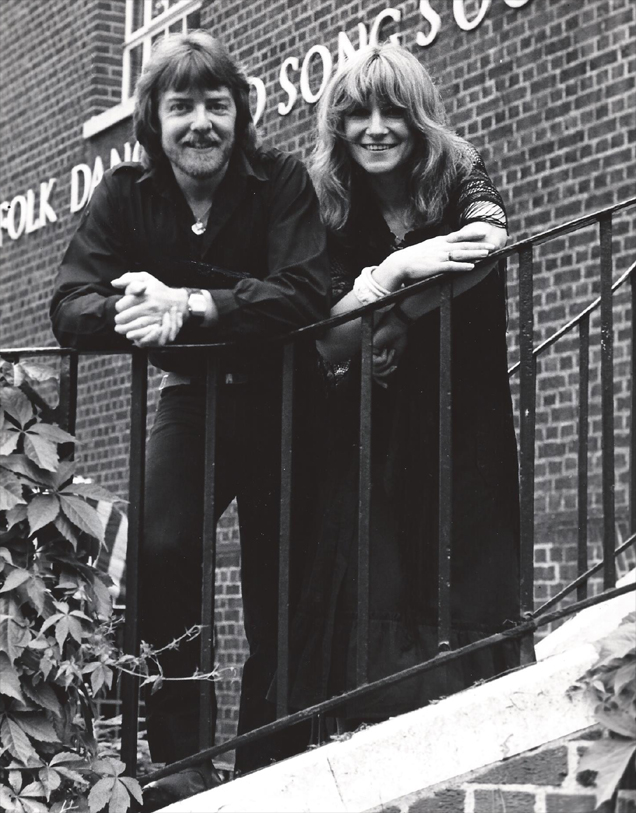

By this time, of course, the lives of both Dave and Toni had changed immeasurably. Toni, after being encouraged to audition by BBC producer and folk fan Peter Charlton, secured a job as a regular presenter of children’s TV staples Play School and Play Away, taking her place alongside the likes of Johnny Ball, Brian Cant, Floella Benjamin and Derek Griffiths. Dave contributed too, writing songs and performing on both shows. “Folk music is perfect for kid’s TV,” he says. “It’s gentle, the tunes are interesting, you can write nice lyrics… it’s an easy way into kid’s songwriting.”

I was curious to know if the short leap from Alex Sanders’ coven to reading stories for Humpty and Big Ted had felt incongruous for Toni, but clearly not. “It didn’t even occur to me that the two would get linked,” she says. “We were hippies, and nobody minded about anything”. She pauses and laughs again. “I remember presenting Seeing and Doing, dressed as a witch and running all over Hampstead Heath. It was a rich time…”

Though Toni and Dave separated in 1993, they remain good friends. Dave continues to write, perform and record music: in 2020, his band Rattle on the Stovepipe released Through The Woods. Available through Wildgoose Records, it’s a hugely enjoyable exploration of traditional American song. He works as a storyteller too, continuing to research magical folk tales and still taking inspiration from “the atmosphere and psychological aspects of magical ritual” he experienced during his time with the Sanders coven. Toni – now Toni Arthur-Hay following her marriage to writer and academic Malcolm Hay – enjoyed a highly successful TV career and has also worked as a writer and theatre director. She’s a fine actor, too: her 1978 Play For Today, ‘Stargazy on Zummerdown’ is an extraordinary piece of television.

And although Alex Sanders died in 1988, the Alexandrian tradition of Wicca continues to attract followers worldwide. It is still practised by Maxine Sanders, whose autobiography Fire Child: The Life and Magick of Maxine Sanders was published by Mandrake of Oxford in 2007.

In the weeks following our conversation, both Dave and Toni enthusiastically e-mail over further memories and photographs, and two parcels of (sensational) home-made marmalade arrive from Toni. They both tell me identical tales of being haunted by the ghosts of US airmen in the former Oxfordshire brothel they called home during the early 1960s. And Toni recounts a hair-raising midnight memory from the 1970s: the huge, cloak-wearing, long-haired figure that strode purposefully past their broken-down car in the shadow of the Rollright Stones, before vanishing completely. “He looked a bit like Ted Hughes,” she insists.

Neither had listened to Hearken to the Witches Rune for quite some time before I contacted them, and I was keen to know, in the intervening fifty years, whether they’d been aware of the album’s burgeoning reputation.

“I still am unaware of it!” laughs Dave. “One thing that amused me… I read some website that had done the 100 Most Weird Records – and it’s on that!”

“We knew it was unique. But the ultimate thing was less good than I would hope for nowadays. It’s difficult to be objective about your own work, and I can hear all the faults and glitches that I’d want to redo. But if you’re a complete outsider, you listen to it from a different point of view and you might get different things from it. And if you do – great! I’m happy for people that find it interesting and worth listening to.”

“I had absolutely no idea, either,” says Toni. “All I can say is thank you very much, because it was a joy to listen to it. I couldn’t believe how high my voice was – dear God, I sound like some sort of wailing Sheela-na-gig!”

They’re being modest – it remains an affecting album, powerfully performed. With its 50th anniversary here or hereabouts, let’s gather the runes for a long-deserved reissue.

Eternal thanks to Dave Arthur and Toni Arthur-Hay. And to Jonny Mohun, Andrew T. Smith, Steve Jones, and William Fowler and Vic Pratt of the BFI for further advice and research. Members of the mudcat.org folk forum were very helpful, too. And highly recommended: Rob Young’s superlative book Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music (Faber & Faber, 2011), which provided invaluable background reading.

Legend of the Witches (together with 1972 film Secret Rites, also featuring Alex and Maxine Sanders) is now available on Blu-ray/DVD from the BFI.