The alluring power of the “wild wood” seemed a constant throughout the typical 1970s childhood, even for youngsters with the most urban of upbringings. The great writers of the era, the Alan Garners and Susan Coopers, used tangled, mystical woodland as the playground for the re-emergent elements of British folklore that dominated their books; a place where dark, ancient forces bled through into the present day. Doctor Who‘s jungles were alien and impenetrable, places where marooned scientific expeditions battled spiky, otherworldly beasties; and Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are updated the surreal wilderness of the nursery rhyme and brought it, tangible and touchable, into every terrified child’s bedroom.

For those of us lucky enough to have local woodland within walking distance of our homes, these tales settled like mist onto every innocuous copse, every “deadman’s creek” on the fringes of a new, suburban housing estate. Even when we stayed within sight of reassuring modernity – railway lines, twine-bound haystacks, Ford Cortinas in lay-bys of dubious repute – the surrounding trees played host to ghosts, goblins, and stranded Daleks alike. And, in the 1980s, a new wave of “swords and sorcery” fiction, spearheaded by Robin of Sherwood and the Fighting Fantasy books, claimed Britain’s woodlands as their own, and another generation of youngsters were entranced; venturing both literally and figuratively into the trees, searching for Herne the Hunter with a twenty-sided dice to hand.

All of these feelings bubble tantalisingly through the textures of Lancashire-based composer Stephen James Buckley’s new album, Flora. Stephen is so infused with the spirit of his local woodland that he even named his recording project – Polypores – after the genus of common fungi that grow around unsuspecting tree roots and trunks, and the album itself is a densely ambient evocation of a fantastical journey through a freakishly overgrown forest, where trees and flowers grow to outlandish, almost alien proportions. The music weaves organic, pulsating synth lines into field recordings of trickling water, rustling foliage and birdsong, and captures perfectly the still, almost claustrophobic power of the woods. I asked Stephen about the album’s origins, in the stiflingly hot summer of 2018…

Bob: That summer was incredible… almost surreally hot and claustrophobic. Did the feel of that hot weather seep into the ambience of the music? I sometimes think really hot days have a kind of hallucinogenic quality to them…

Stephen: Yes, I think the heat definitely did have some kind of impact. The way I write nowadays, it’s very much a subconscious thing, as opposed to something planned or carefully thought out… which was how I used to work for older Polypores releases. So there aren’t necessarily many specifics (“this track is about this kind of fungus growing on this kind of tree”), it’s more a general feeling I’m channeling.

And I say “channeling” because that’s very much what I was doing. I spent time in certain environments, in a certain state of mind, and then went home and the music just came. It was hot, and that can make you feel a bit weird. And I think a sort of trippy heat is apparent on this record. A phantasmagoric humidity. Although the forests I explored were English, they could just as easily be a jungle. If I had unlimited time and resources, then I’d definitely visit a jungle or two.

A lot the inspiration seems to have come from walking in your local woods… can you describe them a little?

I don’t want to go into too much detail about the woods I go to every week, because I’d prefer to keep them a secret. If people from Preston read this then they might start going there, then it’d no longer be quiet and peaceful, and I’d have to look further afield. But I can say that some of the places which inspired – and provided sounds for – Flora were The Fairy Glen near Wigan, Beacon Fell, Brockholes Nature Reserve, and the woods around Roeburndale.

I think the most important forest for me is Great Corby Woods, between Great Corby and Wetherall, in Cumbria. I lived in Great Corby as a child for a while, and my parents would regularly take me out into the woods. That’s when I developed my interest in fungi. My dad would tell me about all the different kinds of trees and plants, and my mum would explain why it was bad to drop litter.

There was a valley in the middle that the River Eden flowed though… which you can see, if you take the train from Carlisle to Newcastle. A little old man lived at the bottom of the valley. He carved things out of wood, and once made me a moneybox, which he hand-painted. The valley seemed huge and steep, and I was terrified of it. I’d have constant nightmares about falling down it. We were once attacked by a nest of wasps, which our dog decided to dig up. I think this forest, and the time I spent in it, informed a lot of who I am today, and I’m forever grateful to my parents for that experience.

Do you still try to vanish to the woods as as possible? Can you describe the appeal?

I try to get into some form of countryside every weekend. Preferably woods, but I can’t always be picky. Although I did it a lot as a child, I think it fell by the wayside in my teenage years and twenties, as I was too busy focusing on crap that didn’t matter. But as I got into my thirties I started yearning for it again. And when I started meditating – which I do every day, as it’s very good for the mind – I think it changed the way my brain worked. I started to appreciate things with a sense of wonder again. I revisited a lot of the things that interested me when I was young – space, nature, monsters etc – and found joy in them once again.

Can you create music in your head while you’re actually out walking?

I don’t compose in my head whilst walking. I tend to try and focus on what’s around me in the moment, taking it all in, rather than thinking about music. I’m absorbing it all for later. Although I’m also often talking to my girlfriend about frogs and birds and stuff.

As you suggested, you made a lot of field recordings for Flora, didn’t you? What kind of sounds were you looking for?

Yes, there were a lot of field recordings… these were often how the tracks started. I’d get some ambience that I’d recorded, put it into a loop pedal, mess around with it so it made some kind of odd rhythm, then work on top of that. Other times, I’d layer in recordings of birds, just subtly underneath a track, to give it a bit of texture.

I basically wanted to create an environment in which these tracks lived. But the field recordings were often heavily manipulated with various effects pedals to give them an otherworldly vibe. I’m well aware that adding field recordings to synthesizer music isn’t a particularly novel thing to do, but the important thing is that I really enjoyed it, and I thought it sounded great, so that’s all I’m really concerned with.

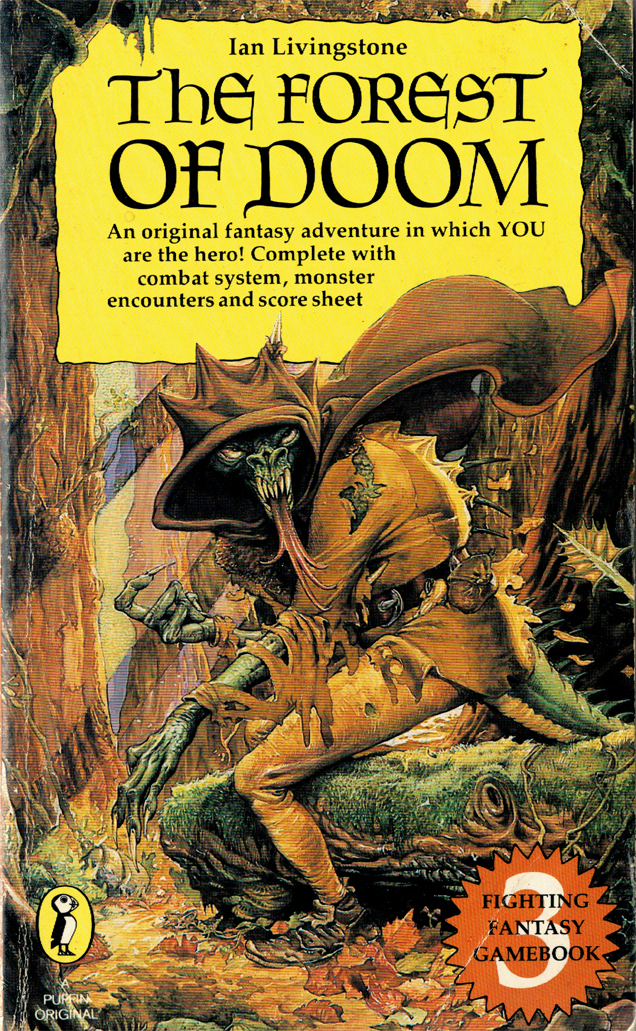

I was interested to read that you started to imagine a “giant” forest when you were making the album… which, for me, brought all kinds of childhood images to mind. Lots of nursery rhymes, but also Where The Wild Things Are, Doctor Who and its various alien jungles, the Old Forest from Lord of the Rings… even the Fighting Fantasy book, The Forest of Doom! Is that idea of the “wild wood” one that you find especially evocative?

Oh, I loved the Fighting Fantasy books! Deathtrap Dungeon was my favourite, but I do remember The Forest Of Doom. There was a bit with a scarecrow that really creeped me out. And yes, the huge forest is something that came subconsciously… like everything tends to with me. The feeling of being overwhelmed by nature, when everything is lush and growing, the smell of the plants and flowers – it’s just all-encompassing if you go in far enough. And that perhaps translated into these massive plants and trees.

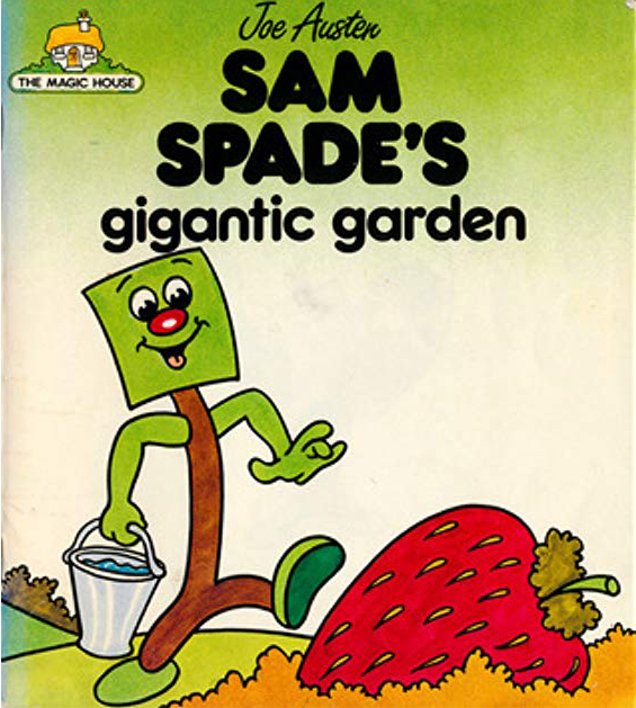

Also, one of my favourite books as a child was called Sam Spade’s Gigantic Garden. It was about a spade called Sam Spade, who used some magic water that he got from HG Well – who was a well with a face – to water his garden. The plants all grew to enormous sizes. It was completely out of control. Something of that size can be both beautiful and alien… and eventually frightening. I think the album has all of those ingredients, somehow. Again, not my intention, but that’s what I channeled, so that’s what came out. I should have thanked Sam Spade in the credits, really.

The idea of unnaturally large flora intrigued me. On the off chance, I’ll ask… when I was a kid, especially when I was tired, I used to get quite confused over the size of things… the bedroom would feel massive, and I would feel tiny… or vice versa. I’ve since discovered this is called Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, and it’s quite common! Did you ever experience it yourself?

I’ve never experienced that, and am sort of jealous that you have. I wonder if there’s any way it can be induced? I’ll look into it.

How did you go about converting the woodland themes of the album into actual music? Is there a synth sound that’s especially “forest-y”?

Again, I didn’t really think too much about it. I just do it intuitively. I think there are certain synth sounds, particularly triangle waves, which can sound a bit like a flute. And flute melodies can often sound pastoral. I’m not sure why… I guess we make that association from their use in the nature documentaries we saw as children. I do like creating babbling brook-type sounds, using fast random filter cut-off. And I have a lot of elements which are out of time with one another, rather than rigidly sequenced. I guess that sounds a bit more natural.

I didn’t do that intentionally, but thinking about it, that’s probably why it appealed to me, and why it therefore ended up on the record. I also quite like having high-pitched, twinkly sounds which just sit above the rest of the sounds, and come in and out… like birds singing. If I went back and analyzed everything, I’m sure there would be a lot more. But I’m very much navigating by feel rather than with an instruction manual.

The closing track, Sky Man, is quite joyous… is this about the experience of seeing the sky again, once you leave the dense woodland behind?

Sky Man was the last track I wrote for the album, I think. It really had a feeling of emerging from something, of rising out of something. A feeling of transcendence and relief. Once that was placed at the end of the album, the whole thing suddenly made sense as a kind of narrative. Almost like Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. The idea of going though something – something vast, beautiful, even scary at times – then emerging from the other side into the light. With the ability to fly! I’m aware of how ridiculous that sounds, but that’s what makes sense to me, so I must embrace that.

I remember around that time I was reading The Vorrh Trilogy by Brian Catling. That’s very much based on an archetypal, mythical forest. I think that perhaps inspired how the album was finalized, in some way.

The album sleeve is utterly gorgeous, and reminiscent of so much 1970s fantasy artwork… including Roger Dean’s legendary prog-rock sleeves. Who did it? Did you have any input into it?

The album art is incredible. I’ve had it for months and was so excited to share it with everyone. It was done by Nick Taylor, who has done a few previous record covers for me. I think I gave him a loose brief involving magical forests, massive plants/fungus, natural history museums, and old sci-fi books. The look of the film Fantastic Planet was also a reference I gave him. He came back a few weeks later with this absolute gem. Nick is very good at interpreting my ideas. I’m pretty sure he used some kind of forbidden alchemy to ransmutate them into gold.

There’s more of his work on the inside sleeve too, which is another reason to buy a physical copy!

Speaking of which, Flora has been released on Colin Morrison’s wonderful Castles in Space label, who put out some gorgeous music… how did you link up with Colin?

I’m not entirely sure how Castles In Space found me. Most of the labels I’ve been released on seem to have a mutual appreciation of each other’s releases, and support each other, and that’s really nice to be a part of. They kind of feed into one another. My first release, via Joe McLaren’s Concréte Tapes, led to me being heard by other labels like Polytechnic Youth and A Year In The Country. These led to me being heard by Front & Follow. They are all listening to each other and supporting each other, so it just kind of grows from there. It’s like a little ecosystem which is great to be part of.

There are also the radio shows like Gated Canal Community, You The Night And The Music, and Soundtracking The Void, which are all linked in with that. I’m grateful to everyone who’s put out my stuff because it always leads to more people hearing me, and wanting to put out more stuff. And I’ll hopefully do more with all these labels in the future. They are all great to work with.

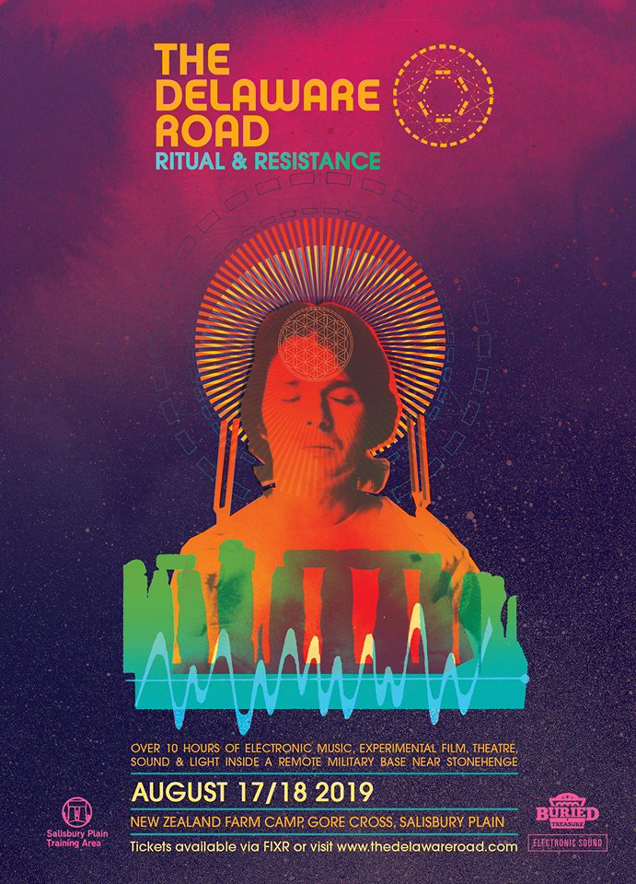

Colin from Castles In Space actually got me on at the Delaware Road event in Salisbury this August, which is going to be amazing. All kinds of music, art, spoken word – in a military bunker! I can’t wait for that, and I’m proud to be representing Castles In Space on their stage there.

The beautiful, vinyl edition of Flora, by Polypores, is still available from…

https://polypores.bandcamp.com/album/flora-4

And Stephen can be found on Twitter or on Facebook. Thanks to Stephen for such a thoughtful and interesting chat, and for sending over some of his own personal woodland photographs. And belated gratitude goes to Sam Spade and his Gigantic Garden.