HERE JOHN TURNER WAS CAST AWAY IN A HEAVY SNOW STORM IN THE NIGHT IN OR ABOUT THE YEAR 1755

THE PRINT OF A WOMAN’S SHOE WAS FOUND BY HIS SIDE IN THE SNOW WHERE HE LAY DEAD

The stone is not especially conspicuous, but it’s not inconspicous, either. It’s just there. We spotted it easily enough from the car window, as we trundled merrily towards the A537. The distilled essence of a 300-year-old mystery, surrounded by tufts of long grass at the side of a dry stone wall in Cheshire, barely ten minutes drive from the nearest 24-hour Tesco and a drive-through McDonalds.

The enigmatic inscription on the stone provided the inspiration for Alan Garner’s moving 2003 novel Thursbitch, a book in which this intertwining of the ancient and modern is a powerful driving force. John Turner is a jagger, a packman, trading salt and malt between Cheshire and Derbyshire, the only member of his tiny community to have experienced an existance outside of Thursbitch valley itself, where a paganistic, hallucinogenic bull-worshipping religion inextricably connects the local farmers to the dark, unforgiving landscape that surrounds them. That connection is threatened when one of Turner’s excursions brings Christianity – and, ultimately, the founding of the still-extant Jenkin Chapel – to the valley, and the echoes of these tumultuous events resound into the 21st century, becoming entangled with the lives of Ian and Sal, a modern-day couple (of sorts) whose regular walking trips around the stones and ruins of Thursbitch lead to the unwitting forging of a symbiotic link between their own touching plight and those of its 18th century inhabitants.

I visited Thursbitch on May Bank Holiday Monday, with my friends Nathan and Natalie. Unlike Ian and Sal, we didn’t appear to drift backwards in time… although the hailstones that engulfed us in the ruins of the valley’s most remote farmhouse certainly belonged to an entirely different season. Like John Turner, we tracked an inquisitive hare as it lollopped from stone to stone, and we stopped for a rest amongst the weather-worn headstones of Jenkin Chapel itself. “This place has had enough of us,” quipped Nathan, quoting Sal from the book, as we lost our bearings amidst a zig-zag of faded tracks.

In the evening, we went to the Old Medicine House. This timber-framed 16th century apothecary was, in the early 1970s, on the verge of demolition before Alan Garner and his wife Griselda transported it seventeen miles across the Cheshire countryside to be rebuilt alongside their existing family home. It now forms the hub of their charitable foundation, The Blackden Trust, an organisation that encourages visitors to uncover the secrets of the surrounding landscape through a delightful cavalcade of workshops, lectures, schools programmes and arts events. Those familiar with the locations of Alan’s books will find the setting oddly evocative… as we approached the house, the supine dish of Jodrell Bank observatory was peeping incongrously through the trees, and the occasional hum and rattle of express trains to Crewe never fail to remind me of the lovelorn Tom, the intense 1970s teenager whose tortured love for his more pragmatic girlfriend Jan forms an integral part of the haunting Red Shift. By the fireside of the Old Medicine House, Nathan, Natalie and I watched acclaimed folk musicians James Patterson and John Dipper perform a gentle, good-humoured set of exquisitely-played traditional songs; the latest of many Blackden Trust events that we’ve attended together. As Griselda joyously commented to us afterwards, their events have become a community in their own right, and it’s an extremely warm and welcoming community.

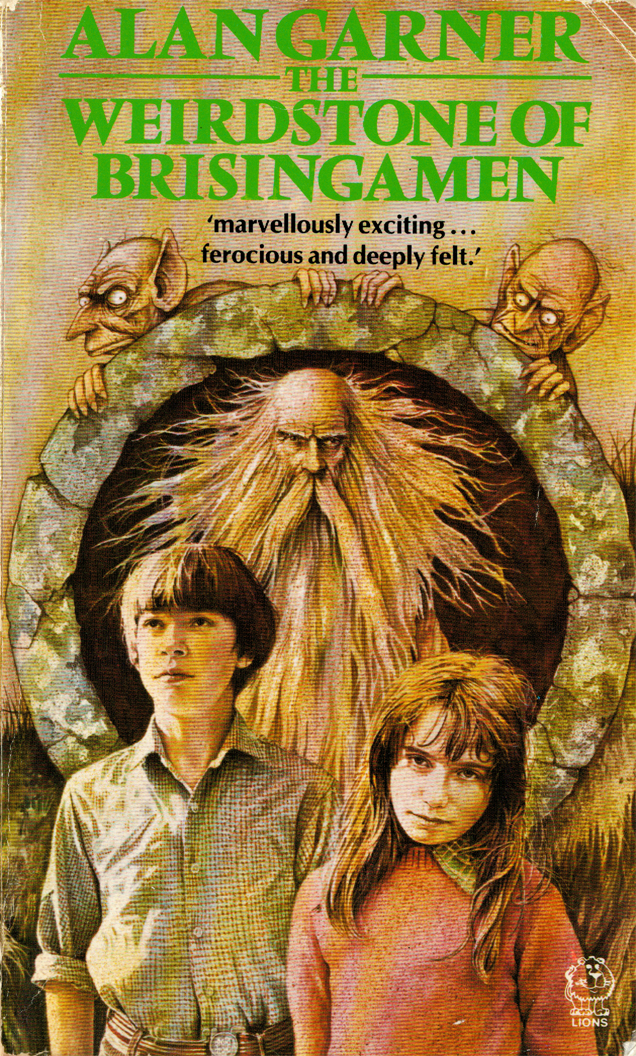

I could ramble endlessly about the influence that Alan Garner’s books have exerted upon the last 35 years of my life… and I suspect that I frequently have. When I first read The Weirdstone of Brisingman and The Moon of Gomrath at the end of my time at primary school, I transplanted their captivating, mystical storylines into the setting of my native North York Moors, the only comparable countryside that I’d experienced in my short lifetime. Those books gave me a connection with, and an appreciation of, my own locality and landscape that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. As the years roll by, I find increasing solace in losing myself amidst the rolling moors of my childhood, submerged by their stories, their folklore, their people, their ancient stones and valleys, their sheer power. Alan Garner gave me that, and I’ll always, always be grateful.

I’ve tried to tell him in person, but his presence renders me incapable (well, more incapable) of coherent speech.

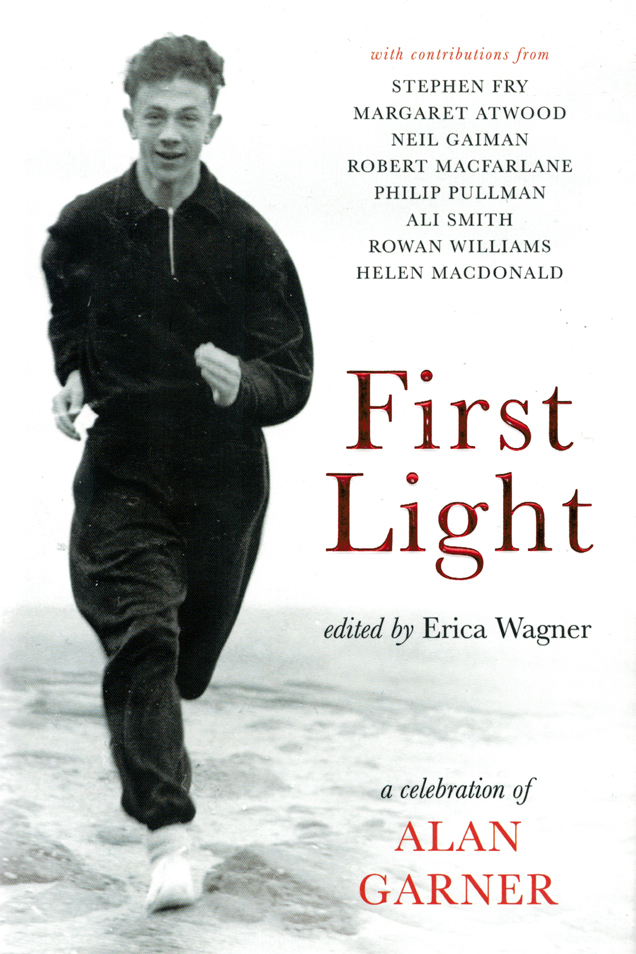

In 2015, on my first visit to the Blackden Trust, I discovered that writer and editor Erica Wagner was compiling a compendium of appreciation of Alan’s work, entitled First Light, with contributors that included Stephen Fry, Neil Gaiman, Philip Pullman and Margaret Atwood. I interviewed Erica for the Fortean Times, and the following feature appeared in Issue 336, dated January 2016. It’s a love letter to First Light, which is an inspiring and hugely entertaining collection of tributes, reflections and memories, but also to Alan’s body of work, and the influence it has exerted upon us both…

THE WIZARD OF THE EDGE

Bob Fischer looks forward to a new anthology of appreciation for the work of Alan Garner, whose novels of folklore, myth and magic have enthralled generations of readers.

“At dawn one still October day in the long ago of the world, across the hill of Alderley, a farmer from Moberley was riding to Macclesfield fair.”

It’s a drizzly, autumnal afternoon, sometime in October or November 1983, and a softly-spoken primary school teacher, all drooping moustache and bifocals, grips a battered paperback and begins reading the above passage aloud to a whispering gaggle of ten-year-old children. Some are restless, most are entranced; at least one is entirely unaware of the profound impact the book is to have upon his life. And yet, as a sheet of rain dissipates against the library window, and The Weirdstone of Brisingamen plunges swiftly into a murky world of lost magic, dark forces and twisted folklore, I gradually begin to realise that I have found my Favourite Writer In The World.

It might be 32 years since the inspirational Mr Millward read Alan Garner’s debut novel to me and my snotty-nosed classmates, but – in the intervening three decades – my opinion has never faltered. Ever since that fateful afternoon, Garner’s books have been a constant in my life, not just shoved onto a shelf or piled upon a bedside table, but almost woven into the very fabric of my being; whether as a dreamy schoolboy excitedly searching for Svarts and Mara in the tangled woodland of my native North York Moors; or as a beardy fortysomething, keen to research the long-lost folk tales of the very same windswept landscapes.

Garner’s work is primal, hypnotic and essential. I can’t imagine life without it, any more than I can imagine life without oxygen, water or Chocolate Hobnobs. And I really like Chocolate Hobnobs. When I read books like Weirdstone and its soulful, feminine sequel, The Moon of Gomrath; when I revisit the suburban weirdness of Elidor and the simmering, sensual myth cycle of The Owl Service; they occupy my thoughts to the virtual exclusion of everything else around me. Mundane existence feels pale and grey; Garner’s books are thrillingly alive.

And then there are the later works: Strandloper, Thursbitch and Boneland; the latter of which, published in 2012, unexpectedly completed the Weirdstone trilogy five decades after the saga had begun. Infused with complex themes of loss, grief and fractured time, these books have proved as profoundly affecting to adult readers as The Weirdstone of Brisingamen was to those of us whose childhoods it illuminated. Garner’s readers have, in every imaginable sense, grown up alongside him.

Alan turned eighty last year, and – to celebrate – a new anthology of appreciation for his work has been compiled by writer and journalist Erica Wagner. Entitled First Light, it collects together essays, poems and similarly creative tributes from the likes of Stephen Fry, Philip Pullman, Neil Gaiman, Susan Cooper and David Almond.

“Alan Garner is really a unique literary figure,” Erica tells me, on yet another drizzly, autumnal afternoon. “And one thing that’s worth saying is how many different kinds of people – writers, historians and scientists – have been drawn to his work over the years. So it wasn’t hard to come up with a list of people that we might approach to contribute. And somehow I was not surprised when, really, everyone that we thought to ask agreed to do it. And that’s a sign of how important Alan Garner has been; not just to them, but to a broader reading and literary culture.”

Curiously, unlike most of her contributors, Erica’s childhood was completely untouched by Garner’s work, and she offers up the entirely reasonable excuse of having been born and raised in Manhattan.

“I came to Britain as a late teenager, so I didn’t grow up with Alan’s books,” she says. “I discovered his work as an adult, and I can only imagine what their effect would have been on me if I’d read them when I was ten or eleven. The first book of his that I read was a reissue of The Stone Book Quartet, in the late 1990s. At the time, I was editor of the Times Literary Supplement, and – of course – every book that was ever published came across my desk at one time or another. Thinking that I was a terribly well-educated person, I found myself asking ‘Gosh, what is this book that’s being called a classic? I’ve never heard of this book, I’ve never heard of this author… what’s going on?’. So I started to read… and that was it. My life changed.

“Maybe the reason I came to Britain is that I wanted access to another world. I was interested in folklore and mythology, and I felt it was much closer to the surface in Britain. Much more available. So when I discovered Alan’s work, it just spoke to me as the thing that I’d been looking for.”

Originally published between 1976 and 1978, The Stone Book Quartet comprises four short novels – The Stone Book, Tom Fobble’s Day, Granny Reardun and The Aimer Gate – and is arguably the most overt manifestation of the roots of Garner’s work; grounded as it is in the landscape and architecture of his native Alderley Edge; and infused with a sense of his own family history.

“Alan comes from a very interesting and unusual place in modern culture,” says Erica. “He comes from a family of craftsmen. Always rooted in one place, living a kind of ancient life, up until the early 20th century. And then Alan went to Manchester Grammar School, he went to Oxford to study Classics… so he has two kinds of knowledge in his head: the ancient knowledge of where he and his family come from; but then he also has book knowledge. And I think there is, in his books, a kind of fissure; a bridge that always has to be crossed. And I think that’s expressive of that balance. There are always two worlds in Alan’s books. And how those two worlds interact with each other is different every time.”

Even as a ten-year-old in 1983, sitting at Mr Millward’s feet in Levendale Primary School library, I found that this sense of duality was the major contributory factor in drawing me inexorably into Garner’s world. In the early books, that “bridge” is the crossing point from the humdrum to the fantastical; it’s the unassuming rock that conceals the magical gates of Fundindelve; it’s the derelict church in a Manchester slum that provides the portal to the nightmarish realm of Elidor. But more than that; it’s the Weirdstone‘s anorak-sporting hikers, wandering idly through the Cheshire countryside; transpiring – as we discover – to be warlocks steeped in ancient, dark magic. It’s a unicorn loose in an alleyway by a railway line, a Welsh myth cycle manifested in a sabotaged motorbike, a vengeful Celtic spirit unleashed by the excavation of a pub car park. Like the ancient folklore from which he so often takes his inspiration, Garner’s fantasy is not “elsewhere”, in some fictional land… it’s here, and now, and living with us. Beneath every stone, within every hollow tree trunk, lurking in the corner of the attic, behind the water tank.

Within a year of my epiphany on that rainy autumnal weekday, I’d read the first five of Garner’s novels, up to and including Red Shift; a personal literary journey that straddled the terrifying transfer from the warm enclaves of my primary school to the stark, alien bleakness of secondary education. And, looking back, I see the complex passage from childhood to adolescence as another recurring theme in these older books; perhaps a further explanation for my all-encompassing obsession with them at the time. There are echoes of it in Susan’s painful longing for womanhood in The Moon of Gomrath; it’s a driving force behind Elidor‘s textbook “youngest child” Rowland, desperately craving to be taken seriously by his elder siblings; and it positively boils over in the fractious teenage tensions of The Owl Service.

“Yes,” agrees Erica, “the other two worlds are the worlds of childhood and adulthood. It’s frightening. And we don’t talk much about that; we talk about practical things; sexuality, doing your GCSEs, what happens when you go on a date. But my son is fifteen. And I remember being fifteen, dimly, and it’s really scary. And I think a lot of what Alan does is a metaphor for how scary that is.

“Stephen Fry says in First Light that, when he first read Alan Garner, he felt trusted by the books. And I think that’s a very interesting point… one thing that Alan Garner never does is talk down to his readers. His books, which deal in most cases with pretty dark, dangerous and scary stuff, know that these are things that young people think about, and are able to deal with. Need to deal with, indeed. You feel like you’re in a serious partnership with Alan Garner when you’re reading his books. You and the author are on a really important journey together. And I think that’s something that all of these pieces have in common; they’re all describing a partnership with an author.”

Those of us who have had our lives transformed by Garner’s work know that it’s a partnership that lasts a lifetime.

First Light was published in May 2017, and is widely available – and highly recommended. And for more information on the Blackden Trust and its events, visit…

www.theblackdentrust.org.uk

And, as a curious postscript, I’m proud to report that the link between my native Teesside and North Yorkshire landscapes and the books of Alan Garner – forged in my head as a ten-year-old – has become oddly tangible in recent years, with the discovery that the Garner family dinner service that inspired the The Owl Service, with its mysterious, abstract pattern of flower petals and owl faces, was designed by the emiment Victorian aesthete Christopher Dresser, a large collection of whose work is held in the Dorman Museum in my birthplace, Middlesbrough. As part of the the 50th anniversary celebrations of the book’s publication, Alan and Griselda kindly donated a plate from the service to the Dorman… and your shambling correspondant was charged with the responsibility of transporting it across the Pennines. I’ve never driven so carefully in my life, and we kept a constant guard on the car during a toilet-stop at Birch Services on the M62.

If you’re passing through the North-East, please pop into the Dorman Museum and pay your respects, but I accept no responsibility for the compulsive construction of origami owls in the days to follow.

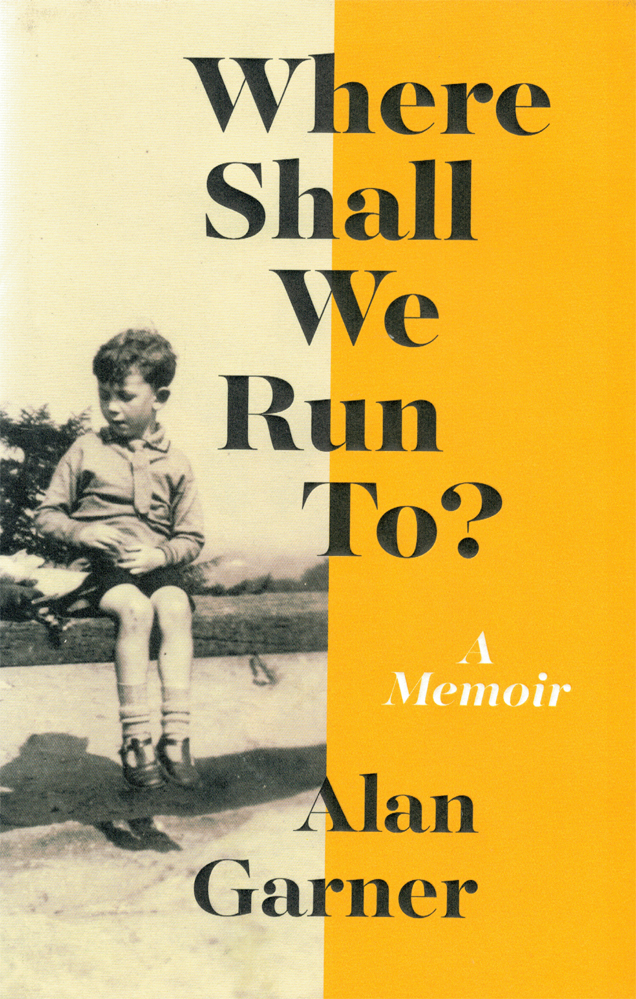

Meanwhile, Alan Garner’s latest book Where Shall We Run To? was published in 2018, and is a touching and evocative memoir of his formative years in 1930s and 1940s Cheshire, written primarily – and ingeniously – from the perspective of his childhood self, and dotted with revelations that shed revelatory autobiographical light on the events and iconography of his subsequent novels. The revelation of his personal involvement in the uncovery of Alderley Edge’s “Goldenstone” left me reeling, and oh… the tale of Bunty the budgie will rend the flintiest of hearts.

I must have been around 10 or 11 years old when I read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. I remember vividly the sense of claustrophobic peril as Colin and Susan scrabbled to escape the underground passages, as if I was there with them. I had to put the book down and literally get my breath back as they emerged into sunlight. This experience from the pages of a book remains one of the most powerful altered states of consciousness I’ve ever had.

Thanks again for a brilliant article. I have a lot of catching up to do with Mr Garner.

LikeLike

Oh, we had pretty much exactly the same experience at exactly the same age! It’s an incredible passage, isn’t it? The part when they emerge from the mines… and then find a Stromkarl sitting casually on the Goldenstone, singing, is the most palpable sense of relief I’ve ever had from a book.

LikeLike

1975 might have been 76 was the year I had the Weirdstone read to me and the rest of the class, and its been with me ever since, and I couldn’t wait for my own children to grow old enough so I could read it to them, and watch their faces to see how it stirred them and got them hooked forever, thank you Alan Garner for a life long gift, though I still start to sweat if I think to hard about trying to turn over in those tight pinning passages.

LikeLike

Oh, that’s lovely. And I’m the same with the underground passages, although it’s worth it to hear the Stromkarl sing afterwards! Did your own kids enjoy the books, too?

LikeLike

Well conveyed, all, and yes exactly my experience, same age when reading Weirdstone, here in Canada, and always visiting Alderley Edge on visits home to Cheshire. We’re very connected to place there. Hope to make the trek to Thursbitch one day, and also a visit to Blackden. Forever thankful for Alan Garner and his writings.

LikeLike