(First published in Mulgrave Journal Issue 1, Summer 2024)

Bob Fischer remembers the day in 1984 when he believed he had entered a parallel dimension. And the location of this mysterious portal? The hedgerow opposite the doctors’ surgery…

It’s Sunday 15th April 1984, early in the afternoon, and my best friend Doug Simpson and I have found a portal to another dimension in a hedgerow on the main road, opposite the doctors’ surgery. It takes the form of a simple, muddy pathway leading away between the bushes. But we’ve never noticed it before, so we jump to the only conclusion that seems either likely or rational – that the pathway has never actually been there before.

Tentatively, we follow it. It leads gently upwards, snaking around a bend, before opening out into a mystical wonderland. For two hard-playing 11-year-olds like us, this is our Shangri-La, our El Dorado, our Brigadoon… a sprawling children’s playpark with swings, a slide and a roundabout, all lying idly silent in pale, Easter holiday sunshine.

We sit on the swings and attempt to rationalise the experience in the most irrational manner imaginable. The pathway – or the “mud track” as it becomes forever known to us – is a portal to an alternate reality, a parallel version of our North-eastern home town of Yarm. And the playpark in which we are sitting simply does not exist in our own, familiar universe. This, we decide, is the only possible explanation for us never having encountered it before.

And then, as we swing lazily back and forth and formulate this outlandish theory, we are visited by similarly intrepid pan-dimensional travellers.

They emerge from the top of a steep bank to our left. One by one, they clamber over a gnarled cast-iron fence and march through the park. A small band of sweat-soaked and seemingly ancient men, all clad in dishevelled costumes from different eras: one Victorian, one medieval, even possibly a horned Viking. “Now then, lads!” hollers their luxuriantly bearded leader, and a few of his party wave half-heartedly in our direction before marching away to the opposite end of the park, out of sight. This is the clincher. We are in a nexus point, a gateway between different realities, and we have chanced upon fellow travellers along the infinite pathways between dimensions.

The story, as I have told it, is absolutely factual, albeit told from our fevered 11-year-old perspectives. We completely believed our versions of events, and even told them to our flabbergasted friends on returning to school a full fortnight later. The truth? Isn’t it obvious? Give yourselves a shave with Occam’s razor and use a generous dollop of Gillette Lemon & Lime shaving foam from Walter Wilson’s supermarket. Doug and I had led sheltered childhoods and had chanced upon a little corner of our home town that we’d simply never seen before. Those pan-dimensional time travellers were railway workers in dirty overalls, knocking off from a morning shift on the line that ran right across the top of the bank, and were probably heading to Yarm High Street for a ploughman’s sandwich and a lunchtime pint.

So where on Earth – or, indeed, where on any of the Earth’s parallel realities – did all this nonsense about portals come from? What was happening in the psyche of two ordinary eleven-year-old boys to make them put such an incredible, outlandish spin on such a mundane, everyday event? Forty years on, I’ve taken to thinking about this in perhaps a little too much detail.

The idea of portals transporting me to mystical realms was something that had been rattling around my head a lot in early 1984. On the final day of term before Christmas, we had gathered in the “end room” of our school and watched a crackly VHS rental version of Terry Gilliam’s film Time Bandits, in which – hey – a small band of sweat-soaked and seemingly ancient men, all clad in dishevelled costumes from different eras, ransack their way through shimmering portals between outlandish, nightmarish fantasy worlds. And then, during the Christmas holidays, I had chanced upon a morning ITV screening of the animated 1979 film adaptation of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. In which, of course, a portal to a snow-covered kingdom is discovered in a dusty closet by a quartet of wartime evacuees.

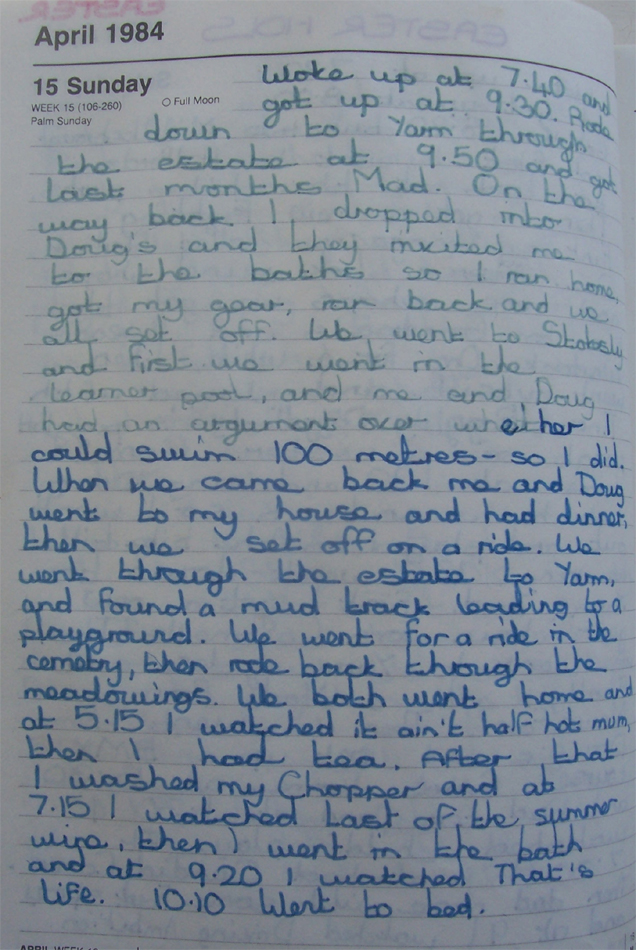

It all clearly fired something in my imagination. My diary – kept meticulously throughout the whole of 1984 – records that, on Saturday 21st January, I went to Hintons supermarket in Middlesbrough and bought a paperback version of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, reading it overnight in my grandma’s spare room while a magically-timed snowfall transformed the streets of Acklam into my own personal Narnia. And then, on Saturday 10th March, my mum returned from a shopping spree in the same town centre brandishing a copy of Alan Garner’s book Elidor, in which four young siblings in 1960s Manchester find a portal to a dying medieval world hidden amidst the rubble of a derelict church in a dangerous slum clearance area.

These stories absolutely entranced me to a degree that clearly began to influence my actual thought processes, and my perception of the real world. But it wasn’t so much the depiction of the fantasy worlds themselves that interested me. Narnia and Elidor look like interesting places to visit, but I’ve never scoured Rightmove looking for properties for sale within easy commuting distance of Cair Paravel or the Mound of Vanwy. What truly captured my imagination was the sheer ordinariness of the portals themselves: that outrageous collision between the outrageously fantastical and the utterly mundane. The very idea of a completely unremarkable child like me finding a pathway to an exciting new reality in his bedroom, in his wardrobe, or in the abandoned building being demolished down the road.

Looking back even further into my childhood, I now realise this fascination had always been there. My favourite film as a four-year-old? The Wizard Of Oz. I’d watched it on BBC1 on Boxing Day 1976, and my tiny heart had been melted by this tale of an innocent young farmgirl transported through the blustery portal of a “twister, Aunty Em” to a surreal, fairytale realm of talking scarecrows and dancing tin men. How I longed to chance upon both in the woods and farmers’ fields around our tumbledown family home in Yarm. My favourite TV show as a four-year-old? Jamie and the Magic Torch, in which a mop-haired young boy shines a Pifco flashlight onto his bedroom floor to create a magical portal to the psychedelic, paisley-patterned world of Cuckoo Land.

I can’t entirely explain why my childhood was riddled with this burning desire for escape to fantastical realms. My parents were lovely, my everyday reality was pleasantly pedestrian – the usual rounds of friends, school and what I repeatedly describe in my 1984 diary as “mucking about”. Perhaps the simple truth is that the desire to believe in other realities, in other realms that exist in such close proximity to our world that they occasionally seep through tantalisingly elusive portals, is a universal one – an intrinsic part of the human psyche.

Certainly our fascination with these surreal kingdoms goes way back beyond Elidor, Narnia and Cuckoo Land. In ancient folk stories and traditions from across the globe, the idea of a hidden “other” world is a constant. Among countless other examples, there is the Celtic tradition of Tír Na nÓg, a supernatural realm of art and enlightenment accessed via caves and burial mounds. There is the Japanese story of Urashima Tarō, a fisherman transported on the back of a turtle to the magical undersea paradise of Ryūgū-jō. Perhaps most enduringly, there is Fairyland, the realm of the Fae, immortalised in Edmund Spenser’s 1590 poem The Fairie Queene and a mainstay of Western literature ever since.

Why did contrasting cultures all feel the need to create these mystical lands? Perhaps simply because life in centuries past was so bloody hard. It was short, violent and oppressive, so the prospect of a better (or at least more mystical) world hidden within tantalising touching distance must have been impossibly alluring. Perhaps, like so many folkloric motifs, it was an attempt to rationalise some of life’s crueller twists of fate. Husband, wife or even baby gone missing? They’re not lying dead in a remote valley somewhere – they’ve been kidnapped by the Queen of the Fae and are actually still alive, just existing on the other side of a portal that remains frustratingly out of reach but that one day might be found on the other side of that funny rock behind the waterfall.

As oral tradition transformed into commercial literature, these real-life portals were immortalised and romanticised in print. I grew up within short driving distance of Hell’s Kettles, a pair of deep, water-filled pools in a County Durham field, noted in Raphael Holinshead’s Chronicles of 1587 but thought to have been created as long ago as the late 12th century. Surely these reputedly “bottomless” bodies of water would lead to some fantastical realm? Charles Lutwidge Dodgson thought so. In 1843, when he too was 11, his family moved to the rectory of Croft-On-Tees, only a mile away. And his imagination became as fired as mine by the discovery of a few mysterious local landmarks. Twenty years later, Hell’s Kettles became the rabbit hole in Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, arguably the most famous portal in literary history.

Since then, our collective love affair with the humble portal has barely waned. From the spectral whimsy of Tom’s Midnight Garden to the brutal, dark fantasies of Pan’s Labyrinth, we find the possibilities afforded by these mysterious wormholes endlessly alluring. As I write, square-eyed streamers across the globe are eagerly awaiting the concluding season of Stranger Things, one of the most successful and acclaimed TV series of recent years. Here, a shadowy laboratory opens a portal to a nightmarish parallel dimension called the Upside Down, and a legion of appalling beasties spill forth to terrorise the unsuspecting inhabitants of a small Indiana town called Hawkins.

I didn’t have the brutal lifestyle of a medieval serf as my excuse for creating my own fictional portal, nor the imagination of a Lewis Carroll as my passport to literary immortality. And even on 1980s Teesside, there wasn’t a hidden government facility conducting terrifying experiments with the supernatural. But that didn’t stop me desperately wanting to find pathways to parallel worlds from my own small town. On 25th December 1984, my wish finally came true… after a fashion. I received my own portal for Christmas: a ZX Spectrum 48K computer that provided a gateway into a multiverse of fictional worlds that I could explore in an immersive, interactive fashion. Completely transported from that pleasantly pedestrian existence in 1980s Yarm, I became an intrepid computer warrior, exploring the 8-bit fantasy worlds of Karn, of Fairlight, and even – brilliantly – of Tír Na nÓg itself. A 1984 adventure game of the same title, released by Gargoyle Games, sees the player adopting the persona of Cuchulainn, an Irish warrior hero of genuine folkloric provenance, searching this mythical realm for the four fragments of the Seal of Calum.

When I played these games, my real world of home, school, parents and even friends ceased to exist. I was, to put it simply, addicted. I had finally found my portal, and it came with rubber keys and a dodgy cassette recorder from Uptons department store. Ultimately, the ZX Spectrum also cost me my close friendship with Doug – I was unable to tear myself away from its fictional fantasy worlds, and we had drifted apart months before he and his family emigrated to Australia in 1985. I am not a gamer any more, but it was no surprise to me to recently learn that the international gaming industry is now a bigger economic force than the global TV and film industry combined. I had Elidor, Narnia and Tír Na nÓg, intrepid 21st century explorers have Zelda and Baldur’s Gate, and – not only that – they pay hundreds of pounds for special fucking chairs that won’t give them chronic lumbago from daily eight-hour gaming sessions. We all still clearly need our personal portals.

There has even been, hilariously, a recent attempt to create one for real. In May 2024, a large circular construction was unveiled in Dublin, displaying a live video feed beamed directly from a similar edifice in New York – and vice versa. Across three thousand miles of Atlantic Ocean, the populace of both cities were able to interact with each other in real time, and the fact that the portals were switched off after a week following a spate of mooning and similarly “inappropriate behaviour” is something that my 11-year-old self would undoubtedly have seen as a glorious triumph of the human spirit.

And the “mud track” and the mysterious playpark that Doug and I found on Sunday 15th April 1984? It’s all still there. It’s called Snaith’s Field, and it was actually created in 1920 by a local benefactor who simply wanted the children of Yarm to have their own green space to explore and enjoy. We took him at his word, making those swings our base of operations for the remainder of 1984. And every time I go back there now, I think of the wonderful day exactly forty years ago when Doug and I found our own very provincial portal.

Mulgrave Journal is the magazine of Mulgrave Audio, the audio drama company I co-founded in 2023. Found out more about us here:

https://www.mulgraveaudio.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen