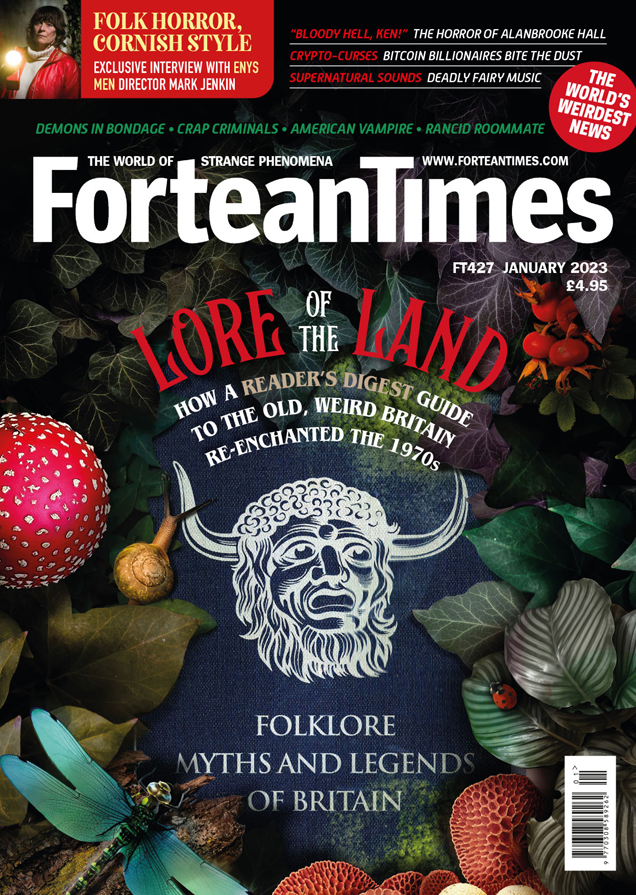

(This article first published in Fortean Times No 427, dated January 2023)

STONED LOVE

Enys Men is an unsettling new horror film from acclaimed director Mark Jenkin, and comes steeped in the uncanny folklore of his native Cornwall. Bob Fischer meets him to discuss mobile megaliths, fragmented time, and unnerving memories of the Padstow ‘Obby ‘Oss

“The Merry Maidens are a circle of 19 standing stones [1],” says Mark Jenkin. “I was told the story as a kid… they were originally a group of girls who were turned to stone for dancing on the Sabbath. This was told to me by my dad, as a myth, but all I heard was ‘This is what actually happened’.

“And the story continues… playing the music for the maidens’ dance were two pipers. And these are two bigger standing stones in different fields. One is in the corner, the other is next to a hedge. And, on the way home from seeing the Merry Maidens, I would always look out for them. And I swear that, as a kid, I would glance through the gateway… and they wouldn’t always be there. They’d moved. So the Pipers were the stones that haunted me. And, as a kid, that fear kept me awake. Although I was intrigued as well – it was the kind of fear you’d enjoy. Which I suppose is the idea of horror films…”

We’re huddled over steaming coffees in a quiet corner of the British Film Institute on London’s Southbank, but the tangled folklore of Mark’s Cornish upbringing never seems far away. His two full-length films to date, the BAFTA-winning Bait [2] and new feature Enys Men, are both rooted in the landscape, culture and alluring wildness of his native county. In the Cornish language, Enys Men translates as “Stone Island”, and a similar sinister megalith is at the heart of the film’s uncompromisingly non-linear plot. So, as a child, did he think the absent Pipers were hunting for him?

“Yeah!” he laughs. “Or they were just hiding. You know… have they gone back to their human form? Are they playing their music for someone else today? That’s where the idea for the film came from. And, as I learnt more about the history of these stones, I became more interested in them. The myths attached to them are Christian – the church was assigning meaning to all this ancient stuff to scare people into conformity. And that’s really intriguing. Why were the Methodists so keen to come into Cornwall to control the working classes? What the hell were we up to? That’s what I wanted to reflect. I didn’t want to make a Folk Horror film in the usual tradition, picking away at the surface of Merrie Old England. I wanted that surface to have never existed. In Cornwall, that wild, untamed, disregard for authority is right there.”

The film, written and directed by Mark, ostensibly follows the plight of a woman – identified in the credits only as “The Volunteer” – living alone on a remote Cornish island and tasked with recording the growth of a rare flower on a rocky outcrop. Unnerved by the presence of that imposing standing stone, she begins to see visions of the island’s tragic past. The dead mariners from a 19th century lifeboat disaster. Victorian mineworkers trapped in a flooded pit, and the pinafore-wearing “Bal Maidens” who wait for them above ground. The island is battered by raging seas and ferocious winds, but the landscape has also been shaped by human disaster. And, although The Volunteer records her observations as taking place in April 1973, time itself begins to unravel. Her only regular contact with the mainland, a fuzzy shortwave radio, broadcasts 21st century news reports and – on her endless forays around the coastline – she finds remnants of tragedies that are seemingly yet to happen. Time slows down, speeds up, runs backwards and ultimately folds inwards on itself. Lichen begins to grow on both the flowers and The Volunteer’s heavily-scarred midriff. It’s a disconcerting and often overwhelming experience.

And, predictably, audiences at preview screenings are already constructing their own theories as to the film’s true meaning. Is this something Mark encourages, I wonder?

“I’m really intrigued by people reading their own meanings into it,” he nods. “Particularly the people who think the film is about grief. And I think it probably is about grief, but it sometimes it takes an audience, or a critic, to point that out and tell you. Because I’m trying to make a film that I want to be multi-faceted, I try not to think in specifics.

“And I think people are sensitive to grief now, because we’re all grieving. I’m thinking particularly about the pandemic… we might have suffered a very specific personal loss, or we might just be grieving for a way of life. We’re very conscious of time now – we talk about pre and post-pandemic. And when we think about time, it’s always linked to grief. When you look at a sunset, and it’s beautiful, why is there a sadness attached to that? You take it in quietly, then the moment has gone, and you’re grieving for it. It’s the Japanese theory of Mono No Aware. The gentle sadness at the passing of time.”

So can I bore him with my own theories about the film? He nods, enthusiastically. The standing stone, I suggest, is sentient, and thrives on grief… and possibly even initiates these human tragedies to feed its all-consuming hunger. Having absorbed the island’s macabre stories for centuries, it begins to play them back in abstract form – rewinding them, fast-forwarding them, splicing them together. So the film Enys Men is actually a filmic collage constructed by the stone itself.

“Proper Stone Tape theory, eh?” smiles Mark. He’s giving nothing away. “So what’s the relationship between The Volunteer and the stone?”

I’m still working on that, I concede. The older version of The Volunteer is also haunted – seemingly – by visions of her younger self, living in the same tumbledown cottage. So is it possible the older incarnation is a simply a construct of the stone, created as an ready-made audience for its own chilling recordings? Honestly, though… don’t treat any of these suggestions as spoilers. I could be miles away from the truth, I’ve really no idea.

“And I’m keeping a poker face!” laughs Mark. “I don’t want to give you any answers. There’s a quote from the French film director, Robert Bresson: ‘I’d rather people feel a film before understanding it’. With all my favourite films, I don’t know if I even enjoy them, let alone understand them. But they make me feel alive, and that’s why I always go back to them. Do you really understand Penda’s Fen? Alan Clarke said he didn’t…”

Ah yes, Penda’s Fen. If there’s a single piece of film-making that feels like a direct antecedent of Enys Men, it’s this totemic 1974 BBC Play For Today. Even the titles feel like nodding acquaintances. Directed by Alan Clarke from a script by David Rudkin, Penda’s Fen depicts the inner turmoil of troubled teenager Stephen, tormented by his own sexuality and a perceived decline in 1970s moral standards. His anguish is played out through visions of angels, demons and – in one memorable scene – the ghost of Edward Elgar. And his torment is ultimately resolved by the landscape of his own surroundings. The rolling hills of Worcestershire are infused with a spirit of Pagan wildness that explosively delivers Stephen from his own, self-imposed constraints of Christian discipline.

“As a film-maker, I’m really interested in Alan Clarke,” says Mark. “But Penda’s Fen was the anomaly for me. It was Clarke’s amazing realism that had always interested me… until, at some point, I got interested in the rejection of realism. Then I finally watched Penda’s Fen and I thought it was just incredible. There’s not another film like it in his body of work. Or anywhere else that I’ve seen. It’s so distinctive. The images in it…”

Stephen waking to find a demon straddling him in his bed?

“Yeah! And there’s no subtlety – it’s just… bang! The fact that we’re having this level of conversation about it all these decades later is what keeps Penda’s Fen alive.”

So let’s talk about time. Specifically, Enys Men’s relationship with time. The splintering and fragmentation of linear time coincides with The Volunteer’s visions and experiences becoming more and more disturbing.

“For me, the scariest thing in horror films is when time stops making sense,” explains Mark. “We impose linear time on ourselves to make sense of the world. We’re born with time, then we choose what to do with it. And, as you grow older, you realise it’s all you have – and it gets shorter and shorter.

“But time is inherently comforting – that routine of time passing. Thinking about the lockdown, I would go to bed and reassure myself that tomorrow was another day and the sun was going to come up. But what if you went to bed and the next day the sun didn’t come up? There’s a film I love, and it got absolutely slated – the third Blair Witch Project [3] film. The brother of the girl in the original film, with his friends, goes to investigate what happened to her, and they find the witch’s house. And they realise, ‘Shouldn’t it be daylight by now…?’ That really sends shivers down my spine. Oh, God… time has stopped. It’s the ultimate horror.

“People’s fear of losing their mind as they get older is often tied into their perception of time. Thinking that the grandson coming to visit them is actually their brother from when they were a kid. There’s a very human fear of time breaking down, and film is the only artform that can really communicate that breakdown. It can depict a very real version of time… but also the dream-state, where we jump around in time and space in our minds. That’s why film is the greatest thing ever created. All the films I really love are preoccupied by that sense of time.”

Nevertheless, certain events in Enys Men are attached to specific dates. A memorial plaque to the victims of the lifeboat disaster pins the tragedy down to 1st May 1897. Were any of the events in the film drawn from real-life Cornish history?

“No, I didn’t want to be too specific,” says Mark. “Every community in Cornwall has a disaster like that. And I wanted to put those people onscreen as humans, not just as a memorial plaque. Same with the miners… the mine where we filmed, West Wheel Owles, had its own disaster [4]. And they say the boys are still down there, they never recovered the bodies. So the actual shaft you see in the film is from somewhere else… we wouldn’t go down that mine. But those who know, know. And the end credits have a dedication in Cornish: ‘For those still out, and for those still below’. So there’s nothing real, but it stands for every disaster at sea or below the ground.”

The 1st May, of course, has its own significance, and is a recurring motif throughout the film. The Volunteer’s observations change dramatically on 1st May 1973, and she is also haunted by visions of Victorian children, clearly preparing for some arcane May Day celebration. In defiance – it seems – of a stern-faced local preacher. Is this the spirit of pre-Christian wildness seeping through again? The date associated with the festival of Beltane is, after all, famously marked by one particular Cornish community. The tradition of the Padstow ‘Obby ‘Oss sees two clanking wooden horses paraded through the town, amid much revelry and merriment.

“I grew up across the water, so when it came to May Day in Padstow I might as well have been born on the other side of the planet,” admits Mark. “It’s for the people of Padstow, and I’m very respectful of that. But I would wake up on May Day morning, and I could hear the sound of the drum coming across the water. It would scare me and entice me in equal measure. It was almost my introduction to the enjoyment of being unnerved by something. And we’d go to Padstow, and follow the ‘Obby ‘Oss… you’d hear it for hours before you ever saw it. Then you’d see the crowds go round the corner, and impossibly the drums would suddenly be coming from behind you. It was incredibly exciting.

“Then I moved to London, and on 1st May I’d go on marches. It was Worker’s Day. The rejection of authority that still runs through Cornwall means there’s never been a great tradition of working class organising, of trade unions, so Worker’s Day was something I didn’t know about until I left. So yes, the 1st May is about rebirth… but it’s also about working people standing up and fighting for their rights. Culturally, it’s a really important day.”

I’ve just got the pun, I tell him. As one of the boats in Enys Men hits trouble off the island’s coastline, a message is heard from the radio: “May Day, May Day approaching!”

“I’d never thought of that!” he laughs. “And now I’m going to use it myself…”

Like Bait before it, Enys Men belongs firmly to the analogue realm. Filmed entirely on location using 16mm film stock, the feature boasts the grainy aesthetic and oversaturated colour of 1970s horror flicks, combined with the unsettling austerity of the era’s most evocative Public Information Films. Mark is celebrating his influences by curating a BFI season of his own favourite films to coincide with Enys Men’s release. Titled The Cinematic DNA of Enys Men, the series includes Penda’s Fen and Nigel Kneale’s classic 1972 TV play The Stone Tape, together with three of the BBC’s Ghost Stories For Christmas: A Warning to the Curious (1972), The Signalman (1976) and Stigma (1977). Also included, tellingly, is Oss Oss Wee Oss, Alan Lomax’s 1953 film document of those famous Padstow May Day traditions.

Mark is also keen to celebrate the contribution of Enys Men’s leading actor. Given a bare minimum of dialogue, Mary Woodvine – Mark’s real-life partner and another long-term Cornish resident – captures perfectly the haunted isolation of The Volunteer.

“It was a massive risk for Mary,” he says. “Physically it’s exposing, but also… I didn’t give her anything to help her. All the normal stuff an actor would lean on, I took away before we started. There’s a great quote about the film from Mark Kermode [5] that puts her front and centre… and she absolutely is.”

And there’s an extra treat for square-eyed TV and film buffs. Playing the aforementioned stern-faced preacher is Mary’s father: 93-year-old actor John Woodvine. From Doctor Who to An American Werewolf in London, from Coronation Street to The Crown, his commanding presence has graced screens of all sizes in a career spanning over 60 years.

“John said ‘I don’t work any more, nobody offers me any parts’,” smiles Mark. “So I said he could be in my new film. I even said ‘Don’t worry, you won’t have any dialogue’. But he actually wanted some! So I wrote him a couple of lines, and – in the end – I gave him a song as well. Normally I hate the last day of a shoot, because everyone is messing about. But we scheduled John for the very final day of filming. He’d just had his second Covid jab, he came over to Cornwall, and it was great. And everyone was so well-behaved because John Woodvine was there!”

And with that, our coffees are finished. It’s been an hour, but it’s felt like five minutes – entirely in keeping with the themes of a film whose mysteries will surely haunt for incalculable non-linear years to come.

Enys Men is now available to pre-order on DVD and Blu-Ray here:

https://shop.bfi.org.uk/enys-men-dual-format-condition.html

For further information, visit bfi.org.uk or enysmen.co.uk. Huge thanks to Mark Jenkin, and to Jill Reading from the BFI.

[1] Fortean travellers keen to investigate this late Neolithic stone circle should head two miles south of St Buryan, grid reference SW432245

[2] Released in 2019, Bait depicts a traditional Cornish fishing village struggling to adapt to a new reality of tourism and holiday homes. Its star, Edward Rowe, also makes an affecting appearance in Enys Men

[3] Simply titled Blair Witch, it was released in 2016.

[4] On 10th January 1893, around 40 miners were trapped by a huge influx of sea water after the detonation of underground charges. Some escaped, but 19 men and one boy were drowned and their bodies were never found. (www.penwithlocalhistorygroup.co.uk/on-this-day/?id=10)

[5] “Mary Woodvine mesmerises in Mark Jenkin’s superbly haunting Cornish gem” – Mark Kermode, Kermode and Mayo’s Take

Why not take out a subscription to the Fortean Times? “The World’s Weirdest News” is available here…

https://subscribe.forteantimes.com/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen