(First published in Shindig! magazine #168, October 2025)

ANGELS AND DEMONS

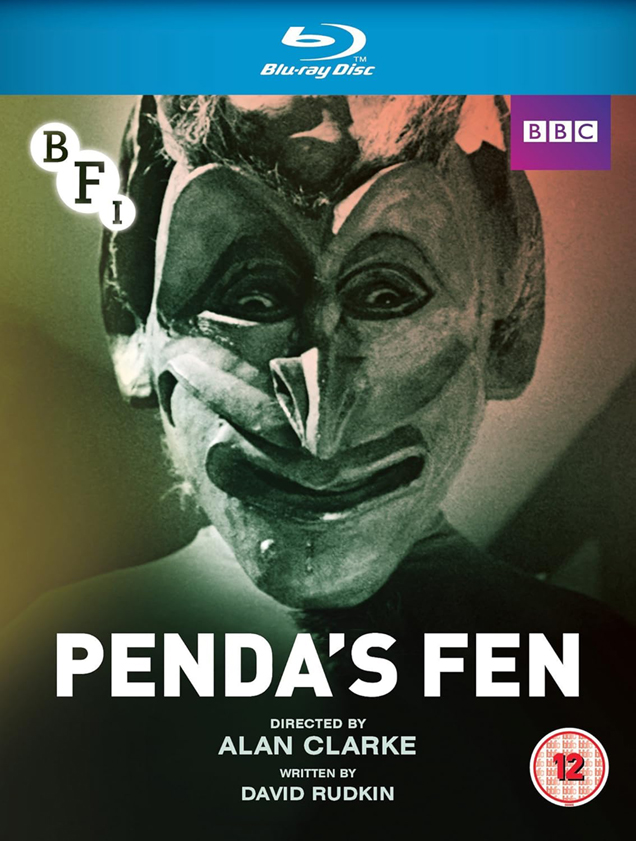

In 1974, the BBC broadcast PENDA’S FEN, a surreal rumination on sexuality and national identity whose themes still resonate today. Angels, demons, a ghostly Edward Elgar and the pagan King of Mercia combine to form a TV drama of beguiling complexity. BOB FISCHER strides purposefully around the Malvern Hills, looking for mis-spelt road signs

“They won’t spot it,” says the elderly ghost of Sir Edward Elgar, genially pontificating from an iron wheelchair in a derelict 1970s farm building. “They have no demon for counterpoint…”

He’s talking about the apparently famous (but still unidentified) melody that provided the inspiration for his 1899 Enigma Variations, but the mystery is one that could easily apply to Penda’s Fen itself. First broadcast on 21st March 1974 as part of BBC1’s groundbreaking Play For Today series, it remains one of the most densely complex but utterly intoxicating dramas ever screened on British television. A delicious tangle of intertwined sub-plots, allegories and its own decidedly demonic counterpoints, Penda’s Fen – over fifty years since its debut airing – is still in no hurry to give up its secrets.

Still, the basic premise is a simple one. In a sleepy corner of Worcestershire in the summer of 1973, troubled teenager Stephen Franklin (played magnificently by former Timeslip star Spencer Banks) is drowning in his own unwaveringly conservative thoughts. Clearly unconvinced by the merits of Slade and Suzi Quatro, he repeatedly listens to Elgar’s choral masterpiece The Dream of Gerontius at volumes that make his parents wince. He is a corporal in the cadet force run by his own single-sex grammar school, and his personal ethics are largely derived from rigidly conformist Anglican doctrines: views that even his father, the local vicar, finds a little too stifling for comfort.

But here’s the rub: Stephen is gay. His emerging sexuality manifests in a cringingly awkward crush on the village milkman, a laddish wag played by a flare-wearing Ron Smerczak, and in erotic dreams inspired by the school’s resident rugger buggers, loutish boors who are already tormenting Stephen for his perceived lack of manliness. At the climax of one such dream, he awakes to find a succubus-like demon straddling him on his candlewick bedspread, and from this moment onwards the battle for his soul commences in earnest.

Penda’s Fen was written by David Rudkin, whose initial inspiration came from a real-life incident that became a pivotal scene in the finished play. His wife, driving home from the school where she worked, found herself diverted from her usual route through the Worcestershire village of Pinvin. The sign announcing the road closure used the archaic spelling “Pinfin”, and Rudkin was intrigued enough to research the village’s history, peeling back layers of linguistic evolution to discover the settlement was originally named “Penda’s Fen” – in honour of the real-life King Penda, the 7th Century pagan King of Mercia.

On screen, the road closure is the result of a mysterious incident in which a teenage merrymaker is badly burned while stopping for a pee on a late-night joyride, and there are rumours (notably aired in a terrific parish council scene worthy of Alan Bennett) that a top-secret nuclear facility is being constructed beneath the hills. Stephen’s inquisitive trespassing past the “NO ROAD TO PINFIN” sign is symptomatic of his own emerging inclination to question authority, and he is rewarded by the visitation of a towering golden angel at the roadside.

Those seeking straightforward folk horror or whimsical telefantasy might be left a little bemused by Penda’s Fen. Rudkin himself has keenly stressed that his intention was to write a “bloody political piece”, and he includes a thinly-veiled version of himself in the shape of Arne (Ian Hogg), an outspoken TV scriptwriter initially reviled by Stephen as man of “unnatural” opinions. The pair strike up an unlikely understanding, and Stephen’s increasing disillusionment with the authority figures of his school and cadet force are fuelled by Arne’s passionate denunciation of “the manipulators and fixers and psychopaths who hold the real power in the land”.

Appropriately, the play’s fantastical elements are given an earthy reality by a curveball choice of director. Alan Clarke enjoyed a career dominated by visceral social realism: Scum, Made In Britain and The Firm. Despite apparently claiming to be baffled by the script, he did a sensational job, shooting entirely on grainy 16mm film and lending the drama an effortless elegance. Clarke’s lingering, static shots of the Malvern Hills are imbued with an overwhelming power, and he brings an intimate sensibility to Penda’s Fen’s more otherworldly moments: not least that extraordinary scene in which Elgar’s ghost (played with heartbreaking frailty by regular Doctor Who Time Lord Graham Leaman) materialises in a barn to convince Stephen that the world is perhaps a little bit more complex than he imagines.

Perhaps ultimately, Penda’s Fen is a rumination on that complexity. At the beginning of the play, Stephen has constructed his own uncompromising moral code, and it’s one of perceived purity in every aspect of his life: his sexuality, his religious convictions, his belief in an incredibly narrow definition of his own Englishness. One by one, these constraints are peeled away, and – on his 18th birthday – the wind is completely knocked from his sails by a revelation that finally destroys his own rigidly self-constructed identity. He is adopted, and his birth parents were from an unnamed foreign country. As Stephen’s adoptive father (John Atkinson) puts it with hilarious understatement: “Even Elgar had some Welsh blood”.

And where does King Penda himself come into all this? That’s probably a revelation too far. Suffice to say his intervention is both thrilling and oddly touching, and it comes at the culmination of a play where the spirit of rural paganism, of an older and wilder England, increasingly bleeds through into repressive ‘70s society. But there is far more to Penda’s Fen than this, and the joy – as the ghost of Sir Edward Elgar himself suggests – is to look for the counterpoints yourself. Good luck chasing down your own personal demons.

Penda’s Fen is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the BFI.

Shindig! is a magazine dedicated to the stranger corners of psych, prog and acid-folk. Check it out here…

https://www.shindig-magazine.com/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen