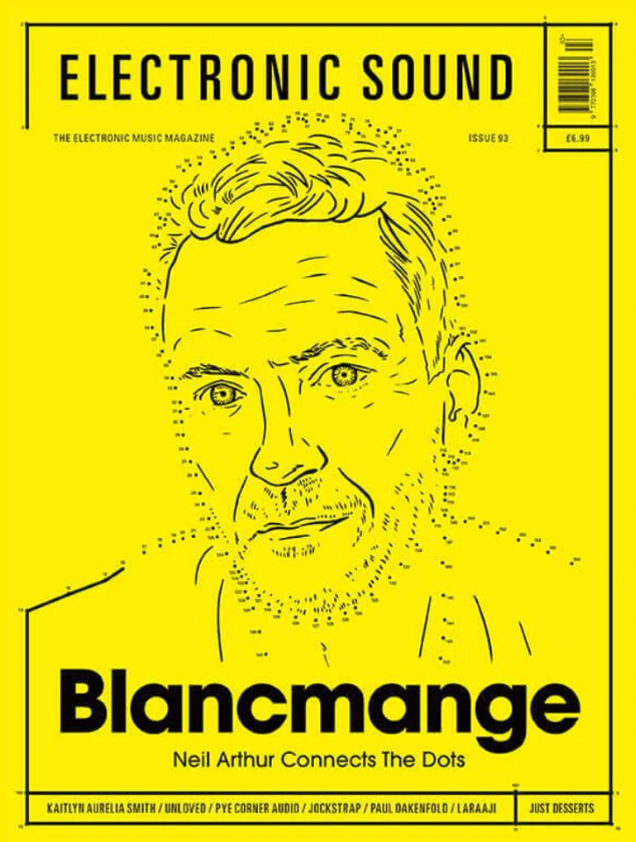

(First published in Electronic Sound magazine #93, September 2022)

JOINING ALL THE DOTS

Forty years after Happy Families, Blancmange are back on London Records with a new album, Private View. But Neil Arthur is looking to the future, and it’s the “bits in between” that are still important

Words: Bob Fischer

“I’ve told you all my stories already,” laughs Neil Arthur.

He’s got a point, but he’s being too modest. It’s a sweaty, sticky afternoon on London’s South Bank, and we’re sitting outside a cafe round the back of the Royal Festival Hall. He’s had a shrimp burger, I’ve had something that sounded slightly posher on the menu but was essentially a cheese toastie. By the time we go “on the record”, we’ve already been chatting for well over an hour. About everything from the antics of his 16-year-old dog Audrey to Blancmange’s early 1980s tours with Depeche Mode and the chess-playing prowess of the late Andy Fletcher. He’s a one-man anecdote machine, and fantastic company. But all his stories? We’ve barely scratched the surface.

And here’s the thing. These tales of derring-do on the High Seas of Synthpop seem – at first – unrelated, bouncing merrily between past and present, between the personal and the professional. But, as you listen intently, you realise Neil Arthur weaves subtle conversational threads through them all. There’s noisy drilling going on outside the Southbank Centre, so we move inside… but it doesn’t disrupt the flow. To quote the title of a key track on the new Blancmange album: ‘Everything Is Connected’.

Including two London performances by Grace Jones, 41 years apart. In June 2022, the modern-day Blancmange performed at the Meltdown Festival curated by the lady herself, at the aforementioned Southbank Centre. Although on that occasion they probably asked the workmen to keep it down a bit.

“To be asked to by Grace Jones to perform, and to play with John Grant…” beams Neil. “It was just fantastic. We did a relatively short set, on a very hot day. Liam Hutton was onstage soundchecking, and he had a pair of shorts on. Him and Finlay Shakespeare. And I thought they were going to get changed afterwards, but you couldn’t go in our dressing room. The temperature was in the fifties! We always do a little ritual before we go onstage, and I just looked at them both. I had my suit on, and those two were dressed like they were going down the beach.

“But 41 years ago, we played with Grace Jones at Drury Lane. It was bonkers. I was working as a graphic designer, just down the road from here. The phone rang, and the boss said ‘It’s for you – make it your last call of the day’. I thought was a mate having a laugh, some bloke saying ‘Grace Jones wants you to support her next week.’ Honestly, I said ‘Fuck off…’ and put the phone down.

“Then it rang again. ‘You! Never swear at me on the phone again. Do you want to support Grace Jones?’ So the next week, I had to go straight from work. The boss never let me have time off. Stephen was working in graphics as well, and we had to finish the day’s jobs before we left. So my partner, Helen, went round to our respective places. She borrowed her mum’s Mini Clubman and picked our gear up, dressed to the nines in this beautiful 1950s dress and high heels. She was thinking she’d just knock on the stage door, and somebody would say ‘I’ll take all the gear in!’. But they ignored her and she had to carry it all herself.

“Anyway, we set up like Morecambe and Wise in front of the curtains. We ambled on, Stephen started the cassette player with the backing track, and I was still playing guitar at this point. ‘I Can’t Explain’… all that stuff. We came off, with a few people giving slow handclaps… but then we watched Grace Jones, and our worlds changed. It was the best performance we’d ever seen. She was climbing up the PA, changing costumes, balancing along a bar between the audience and the orchestra pit in high heels and this fantastic blue suit.

“So we both said ‘Right, let’s learn a lesson from this. Tomorrow, we put suits on’. And we basically got dead men’s suits from Oxfam. So we now had this slight protection. A barrier, and in a way that allows you to give a bit more. I’m sure we still sounded pretty ropey, but it was a big moment. Afterwards, we all ended up in the dressing room sitting on Grace Jones’ knee. She said ‘Come here!’ and I sat on her knee for a bit… then Helen had a go… then Stephen had a go! Then she wanted to go clubbing, so we went to a place called Cha-Chas and did a bit of gyrating. Bloody amazing.”

We’re both chortling away now, to the bemusement of the afternoon bar staff. But hang on, rewind here. What’s the Blancmange pre-show ritual? He wags a warning finger.

“Ah, that’s a big secret. We’ve done it forever…”

Are there props involved?

“No props.”

A chant?

“There is a certain noise.”

A bodily function?

“Nothing voluntary…”

The bittersweet story of Blancmange is like the plot of some great, unmade Richard Curtis synthpop film. How Neil Arthur and Stephen Luscombe went from manipulating recordings of 1970s kitchen utensils to celebrating a string of 1980s chart smashes. How the band split as the hits waned, how a fame-weary Neil retreated into film soundtracks before the duo reformed for acclaimed 2011 album Blanc Burn. How Stephen, faced with spiralling health issues, was unable to join the subsequent tour but gave his blessing for Neil to continue without him. How excellent new Blancmange albums have since appeared at a relentless rate, with producer Ben “Benge” Edwards the new collaborator-in-chief. But also how the friendship between Neil and Stephen has maintained, even flourished. He talks about his former bandmate a lot. And, indeed, his partner Helen… yes, they’re still a couple. Richard Curtis is on his second side of A4 as we speak.

“Helen and I have had our ups and downs, but we’ve been together for over forty years now,” beams Neil. “Oh God, don’t mention that! Just say we’ve been together a long time! She’s put up with some stuff, I tell you.”

Elements of these experiences are woven throughout the new album, Private View. And the lyrics, often intriguingly obfuscated in the past, are becoming decidedly less cryptic.

“I tend to leave a little ambiguity in there, but it’s getting less disguised,” he agrees. “Still, I don’t really want to the album to come across as being about me. Some songs are, and you can’t help that. But some are about other people’s experiences. There’s been plenty of ammunition over the last few years, hasn’t there?”

True, but what’s great about Blancmange is that the songs never feel like they’re self-consciously about Big Things. Even when they are, there’s a kitchen sink approach. Take the aforementioned ‘Everything Is Connected’: “Hang the washing out / Do the washing up / Close the door and then lock it”.

“Yeah, it’s the bits in between,” he agrees. “The cracks. Sinks that need fitting and washers that need changing… I’m really into that.”

The same lyrics take unexpectedly dark turns, too. There are references to Lake Coniston being spread across “two tabloid pages”. Are these his childhood memories of the death of Donald Campbell, killed in a 1967 attempt to break the Water Speed Record?

“That was a big, significant moment,” he explains. “I’m always interested in what’s next… what’s ahead of us. But I noticed those ‘bits in between’ can apply to the past as well. I’m 64, and all these things have happened in my life. And I started thinking about them being connected. The references in that song are about painting a picture, and one of those references is Donald Campbell. It was a shock, and I’ll never forget it. I remember the headline from the Daily Mirror: ‘She’s Tramping, I’m Tripping, I’m Gone”. He was narrating the end… of himself. As a young kid, I thought ‘Oh my goodness – this man has just told us he’s dying’.

“So it was just linking all those things. Here we are, moving along. We put the washing out, we bring the washing in. I do it on the song ‘Private View’. I was thinking about the difficulties everyone is going through, and about the people that aren’t here any more. For example, when my father died, I was there. And much as I loved my dad, I hated seeing him suffer. So I had this mantra: ‘You can let go…’”

That’s incredibly touching, I tell him. My own father is seriously ill, and it’s an awful thing for a family to experience. You desperately don’t want to lose them, but seeing them cling on is just heartbreaking.

“It is, and there won’t be one family that hasn’t been through what we’ve been through”. He smiles reassuringly, then takes a deep breath and finds the lyrics to the song on his phone.

“It’s easier for me to sing it,” he says. “They’re really simple words: ‘What could have been / What might have made you better / What might not have been / Let go, let go…’”

And, at this point, he’s too overwhelmed to continue. He puts a hand over his face, and the tears begin to flow.

“I’m sorry. Obviously, it’s upsetting. This was years ago, and I’ve since lost my mum. But I’m not feeling sorry for myself, it’s what happens with life. Two things are certain: you come, and you go. But then I move on in the song, and I say ‘You should grab hold of everything…’ You know, do you need to carry your shitty baggage around with you?”

He carries on with the lyrics, but it’s clearly tough going.

“‘Happy showers come and go / Migrating birds have my view / Have a pleasant trip…’ I’m sorry about this, it’s very embarrassing. Grief never leaves, but what you have is the opportunity to learn to live without somebody. You won’t get over it, and I can’t. But everything has got to carry on. The song is called ‘Private View’ because it’s very personal. But I wanted it to be out there as an emotional thing, and of course I disguise my lyrics a little bit – it’s not straight down the line. But somebody might just pick up on it and go ‘Shit, yeah…’”

We’re both now trying to compose ourselves.

“I feel a complete wally now,” he says, shaking his head. “You get this stuff out of your system, but what you don’t want to do is burden everyone else with it.”

Go on then, tell me about your dad in happier times. Let’s do some nicer “bits in between”. What was his job?

“He worked as a foreman in a textiles factory,” says Neil. “And my mum was originally a seamstress, but then worked for a company called Walpurmer – which became Crown Paints. She used to say she worked on the VD machines… I mean, what was going on in that paint factory? She meant VDU!”

And we’re laughing again. And that’s another thing I love about Blancmange. The music – and our conversation – is still infused with a gritty sense of very Northern humour. The ribald wisecracks of factory floors, told with the earthy resilience of a man who’s seen his fair share of dogshit in rusty Lancashire bus shelters. Despite it being 45 years since the teenage Neil Arthur left his native Darwen for the moderately bright lights of late 1970s London.

“Yeah, it comes out doesn’t it?” he smiles. “It’s ridiculous…”

Let’s talk about music. Let’s talk about Benge and – indeed – guitarist David Rhodes. Forty years after adding understated guitar lines to Blancmange’s 1982 debut album Happy Families, Rhodes has brought equally tasteful textures to Private View.

“He’s a fantastic friend,” beams Neil. “And I know he’s busy, so it was great that he was able to play on this album. He’s brilliant, and he doesn’t overdo it. That’s one thing I’m still learning: finding the confidence within yourself to think ‘That’s enough…’

“Again, it’s about those bits in between. I learned this from working on film soundtracks. Rather than having music all the time, when the music does come in, it serves a purpose. And when you’re writing songs, there are spaces too. It’s the same with lyrics: I start with a lot, but then I think ‘You don’t need that… or that’. I end up whittling them down, and I do the same with the music. With the help of Benge.”

Ah yes, Benge. The de facto “other half” of 21st century Blancmange, and also Neil’s musical partner in Fader, the duo’s experimental side project. Given that the two outfits have essentially identical line-ups, how does the approach differ? Quite profoundly, it seems. And the explanation offers a further fascinating insight into the “Everything Is Connected” school of Neil Arthur lyric-writing.

“With Fader, Benge gets together a load of instrumentals, and sends them to me,” he explains. “I have a think, then start writing lyrics. And, every so often, I chop and change the arrangements. Then I send them back with vocals… and that’s effectively Fader. That’s been the process for all three albums. Although the last one was slightly different: instead of Benge sending a track called – say – ‘Moog 105’, it was called ‘Porcelain’. All ten pieces were named after paint samples because he’d been redecorating his house! And I used them all as cues. ‘Porcelain… OK, black Porcelain. That sounds like it could be a Black Maria.’ And that made me think about the miner’s strike, and all kinds of other stuff from the late 1970s and early ‘80s. He sent one called ‘Serpentine’, so I wrote a song about me and Stephen. Years ago, I went round to see him, and he hadn’t been well, but I went swimming with him. A beautiful day, and he took me to the Serpentine. Nobody else was there, we just swam up and down and felt fantastic for it.

“With Blancmange, the difference is that I start the songs. Not that Benge doesn’t get involved with that, but I usually have the song structure and lyrics in place before I send them to him. So Fader and Blancmange have fundamentally different starting points, even though it’s the same two people.”

Restlessly prolific since that 2011 comeback, the pandemic years have sent him into overdrive. He tries to count the albums – by both Fader and Blancmange – on his fingers, starting from early 2020.

“Mindset… then Expanded Mindset… then Nil By Mouth III… then Commercial Break… then Nil By Mouth IV and V, then the Fader album, Quartz… and now Private View.”

It’s a hell of a run. Does he work office hours? He shrugs.

“I don’t go in the studio unless I’ve got something. But this is a job, and I have to work. It’s not ‘Ooooh, I think I’ll make another album’. There’s no great big fucking mansion. That never happened. I want to work, I have to work, and I’ll never retire.”

He pauses with a playful smile.

“I might decompose…”

There’s further “Everything Is Connected” news. Four decades since Happy Families, Blancmange are back on London Records.

“I’ve had to pinch myself!” laughs Neil. “I’d written the new album and sent it to Benge. At that point, my manager said ‘What about letting other people hear this?’ So London had a listen to the demos, and thankfully they immediately said yes. It just made sense. It’s been forty years, and they’re a lovely group of people. With the backing of London, what an opportunity for people to say – hopefully – that this album is still relevant.”

So, back in the early 1980s, was it London that helped transform the experimental Blancmange into a bona fide pop machine?

“Yeah, once we’d signed, it was pretty sharp,” he smiles. “But our meanderings before that were really exciting, too. Working with Stevo from Some Bizarre… and our friend Dave Hill using his tax rebate to help us make [1980 EP] Irene & Mavis! I was young, and we enjoyed the journey. Hearing ‘God’s Kitchen’ on the radio for the first time… I remember driving down the motorway, and it came on Peter Powell’s ‘Five 45s At 5.45’. We were on our way to the Brunel Rooms in Swindon to play in front of fifty people, and we went across three lanes of the M4!’

‘Then, of course, ‘Living On The Ceiling’ happened and it was… BANG. I remember getting the call to do Top of the Pops, and we got there really early. I was so excited. I had a beer in the car thinking ‘What am I doing? This is ridiculous’. It was only half past eight in the morning, but for me it was seven o’clock in the evening and I was ready for a pint.

“They did run-throughs for all the camera angles, and I could see somebody in the shadows singing ‘You keep me running round and round, well that’s alright with me’. I thought ‘Who the bloody hell’s that?’ It was putting me off a bit. Then the lights went up, I looked down, and it was George Michael. He knew the lyrics better than me.”

Did the suits help at that point? The “dead men’s suits” they’d bought after seeing Grace Jones? A couple of weeks prior to our meeting, Neil had tweeted a picture of himself wearing the Indian-style linen tunic he’d first sported 38 years earlier, in the video for ‘The Day Before You Came’ – an Abba cover flavoured with the santoor and tabla of regular collaborators Deepak Khazanchi and Pandit Dinesh. Did the clobber make a slightly overawed 1980s pop star feel more at home with the trappings of celebrity?

“Yeah,” he smiles. “Stephen got into wearing a sari onstage, and Dinesh put the bindi on our foreheads. I remember playing a beautiful theatre in Paris. We were in the dressing room, and they all said ‘Right, we’re going on…’ so we did the secret ritual, then they left me alone to gargle because I’d been ill. ‘I Can’t Explain’ started, and that was my cue – I had to get onstage for the fourteenth bar. And I suddenly realised I didn’t know where the stage was! It was literally Synth Tap. I had to shout for help from the tour manager. And I heard him shouting back ‘Arthur! Arthur! Where the hell are you?’ I said ‘I can’t find the stage and I can’t find you…’

“Eventually I ran onstage, but I’d missed my cue. David Rhodes and Dinesh were in hysterics, and Stephen had his back to me in his sari. I thought ‘Oh God, he’s really pissed off with me’. So we got through the whole set, came offstage, and I said ‘What’s the matter with Stephen?’ And apparently, when they went on, all the lights had been down and there was dry ice everywhere. He’d walked across the stage, tripped over his monitor, and knocked both his keyboards off their stand. That’s why his sari was only half on, and his bindi was smudged…”

See? He’s like the synthpop Peter Ustinov. He must have made loads of friends in the music world, I wonder? We’ve already established that Depeche Mode’s Andy Fletcher was the undisputed chess champion of early 1980s pop.

“He was, but we beat them at swimming!” he laughs. “In Guernsey. Bloody brilliant. I used to do a lot of swimming, and Stephen was keen too – so we challenged them to a competition and we whupped their arses. There was only two of us, and we still beat ‘em! We were good mates with Vince Clarke in particular. And in terms of other musician friends, I knew people, but I also had the same group of mates from up north and from college down here. And Helen, obviously…

“But we were suddenly doing Top Of The Pops, and the song was a hit, and I’d go down the shops. And I’d be walking around with people following me. I’d have people coming up in the pub saying really nice things, and others saying ‘Are you looking at my girlfriend? I reckon you are.’

“So when we stopped doing it, I was quite happy to be out of the way. But there’s no therapy for the comedown. You don’t get any help. For a while I was making music, and if you’re successful there’s a tag that comes with that: ‘Pop Star’. But once that stops, what do you do? I was lucky, I had a friend who had just started directing and offered me work making film music. But between jobs… well, there aren’t many musicians that can’t decorate.”

Including Neil Arthur?

“Yep! Of course. I did it for friends, and for friends’ mums. You’ve got to get on with it. But I did find things quite difficult. Sometimes you’d go in a pub and be recognised, and you’d rather that didn’t happen. I’d be going round the shops with Helen, and we’d be picking up our beans and toilet roll. And they’d come up and say ‘Where’s Stephen?’ I’d say ‘It’s not the fucking Beatles, and that was only a film!’” He laughs. “Do you think it’s The Monkees? It’s only Blancmange…

We’re back to Helen again. She’s clearly his rock.

“There’s a pun in the title Private View,” he reveals. “Because Helen is a painter, and we’ve got lots of friends who are artists. One of my regular walks when I lived in South London was to get off at Charing Cross and walk across Trafalgar Square to the National Gallery. I realised you could actually walk straight through the gallery to the street at the other side. You could have your lunch in there! And Helen was away in Barcelona doing an MA in Fine Art, so I’d go and sit in front of our favourite painting: ‘Doge Leonardo Loredan’ by Giovanni Bellini. It’s absolutely beautiful.

“This was the early 1990s. I got some songs together for a project called Delirious. Neil Arthur is Delirious! David was involved, plus Mark Nevin from Fairground Attraction – and Graham Henderson, who I’d done film music with. And one of the songs on the album went ‘I sit before your favourite painting’.

“And I thought… this is an interesting way of writing. You just write about exactly what’s going on. No more, no less. And the album came out, and ‘One Day One Time’ got Single Of The Week from Chris Evans on Radio 1. They got me up to do an interview at half past six in the morning, ‘Really liking the single, mate!’ But it jumped when he played it, and when he came back on air he said ‘That’s a lovely new single from Neil Arthur, ex-Blancmange, but record company… please get some decent stock to me’.

“So I think it took the label slightly by surprise, and they hadn’t got any stock out to take advantage. And your moment’s gone, really. Back to your nice film music. No more photographs, no more interviews. But I liked that. And that didn’t change until we got the songs together for Blanc Burn.”

When Blanc Burn emerged to great acclaim in 2011, what – I wonder – were his ambitions for the reformed Blancmange? Did he expect to be sitting here with another new album to promote, 11 years later?

“I was hoping we’d be able to tour, and at that point Stephen’s condition meant he was OK going into the studio,” he recalls. “But, as we worked on the album, it became clear there was no way he was going on tour. And he just said ‘Get out and bloody well do it’.

“So I did the tour, and it was ‘Well, what now?’ And the logical thing was another album. We toured Happy Families for its anniversary, but I wanted new songs to offer people as well. I do reminisce, but I don’t want to live in the past. I want the risk. Some people don’t and I appreciate that, but I want to keep moving forward. I’m very happy to look back at things, and some things I’d change and some things I wouldn’t. Not with Blancmange, though – that’s done, and that’s it. I’ve made far greater mistakes in life than any mistakes I’ve ever made with Blancmange…”

Well ‘Take Me’, on the new album, seems pretty confessional. Are we back to Helen again? “This is hardly a honeymoon / Picking up where we left off / Clearing pieces after the battle”…

“Yeah, I carry the weight of whatever mistakes I’ve made along the journey,” he says. “And you have to learn from them. Nobody goes through a very close relationship with a partner without making some mistakes, and it’s a case of… how many times will that person put up with it? And how many times will you put up with it? It’s a song from both points of view. And there’s a bit of wordplay – ‘Take me!’ – there’s a sexual innuendo there, Bob! But it’s also ‘Take me…’ somewhere nice. To that dream world, to that perfect zone. And thank you for constantly putting up with me.”

Has he been that bad? I don’t believe it. I have a decent radar for a wrong ‘un, and it’s not even twitching.

”Do you want me to get her on the phone?” he laughs. “No, I’m a good lad, really. And obviously I’m aware of other situations that friends have shared, or that I’ve read about. They all get stuffed into the Blanc Blender! Everything is connected…”

Neil Arthur looks fantastic. Lean and tanned, with cropped hair and beard, he still plays proper, competitive football in an Over-50s FA League. We discuss the fortunes of his beloved Blackburn Rovers, his fascination with white plastic chairs, his current favourite album (“Waves by Low Altitude – absolutely bloody gorgeous”) and the cover art of Private View – a pixelated photo of his art student daughter, Eleanor. Four hours have passed. The lunchtime diners have vanished, tables have been wiped clean. It’s still baking hot, and they’re still drilling round the back of the Southbank Centre. Touchingly, he contemplates paying a surprise visit to Stephen Luscombe.

“I haven’t seen him for a while, but we exchange ridiculous messages,” he smiles. “He’s Irene and I’m Mavis, so when we message each other it’s ‘Hi, Reen… Love Mave’. We’re like chalk and cheese, and creatively that was fantastic. But I think Stephen would agree it can also be destructive. You get the best out of each other, but it ends up like a marriage. So it ran its course, and one of the reasons we originally stopped was – I think – to save our friendship.

“With hindsight, maybe we should have got some help and carried on. But… we did a Greenpeace thing, standing with John Hurt next to an inflatable whale in Hyde Park – as you do – and then went off to do a concert at the Royal Albert Hall. It was great to play there, but I was looking around thinking ‘For some reason, I’m not enjoying this. Everyone we’re working with is lovely, but it’s lost its Blancmange-ness.’ We were becoming a victim in the machine. We were up to the writing, but it was the business side. And it was my fault because I should have been aware of it, but it wasn’t easy to turn that off and I probably made it quite difficult for other people around me. So when I walked away, it took a while to settle down. But I was very, very happy to remain friends with Stephen.”

So, forty years on, is this a different Neil Arthur?

“I think, when I was 24, I probably thought I knew more than I actually did. The one thing I’m certain of now is that I’m not certain! And I’m very comfortable with that.”

It’s that whittling down again, isn’t it? I saw a great quote from Bruce Lee recently: “It’s not the daily increase, but the daily decrease. Hack away the unessential.”

“That’s good,” he nods. “Bloody hell. You know what, I went to the rubbish dump yesterday. I took a load of stuff that had been in the shed for ages. As my dad would have said, ‘Oooh, that’s a nice piece of wood, that’. Anyway, Helen and I got it all outside, and some of the wood had warped. I sawed it up and left it out, thinking somebody might take it. But nobody did! So I took it down the dump with a load of other stuff – including VHS cassettes of all the films I’d taped over the years. Helen said to me ‘Have you ever watched them?’ I said ‘I’m never going to watch them’. ‘So why are you keeping them?’ ‘I don’t know…’

“So we applied that to a load of boxes, and I felt like I’d lost two stone. It was brilliant. I chucked it all away, in all the right skips to be recycled.

“And someone said the other day, ‘Do you mind doing your old songs?’ And I said ‘No, I’m into recycling…!’ But there have been so many new albums since 2011, and that’s where I am.”

Everything is connected. All those “bits in between”, and – especially with the return to London Records – even the two separate incarnations of Blancmange. But, with the ever-restless Neil Arthur, there are always new stories to tell.

Private View is available here:

https://blancmangemusic.bandcamp.com/album/private-view

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen