(First published in Issue 111 of Electronic Sound magazine, March 2024)

ONLY CONNECT

Kim Gordon made her name with US rock giants Sonic Youth, but her second solo album The Collective continues her intriguing exploration of fractured hip-hop beats and “abstract poetry fucked-up shit”

Words: Bob Fischer

“Who’s your favourite Peanuts character?” asks Kim Gordon with a welcoming smile.

It’s an unexpected start to the conversation, but – as her Zoom window had sparked into life – I’d been unable able to resist complimenting her on a Snoopy mug filled with steaming coffee. It’s Charlie Brown, I tell her. I identify with his hangdog world-weariness. Although if we’re talking male grooming and personal hygiene, I’m with Pigpen all the way. And hers?

“Mine is Linus,” she replies. “I named my dog after him! He’s always underestimated, and people think he comes from a point of weakness. But he’s actually the smartest kid. And he has his comfort blanket, which people make fun of, but it can also become a weapon”.

It’s 10am in sunny LA for her, 6pm in frozen Middlesbrough for me. We’re separated by half a world and at least 15 degrees celsius, yet here we are discussing the character traits of Lucy Van Pelt’s younger brother in little fuzzy rectangles on our respective screens. This global interconnectedness – with fewer overt references to Snoopy – also forms part of the inspiration behind The Collective, Kim Gordon’s second solo studio album since the dissolution of Sonic Youth in 2011.

It’s a compelling assembly of stream-of-consciousness lyrics, hip-hop beats and buzzsaw guitars, and the publicity comes with a personal statement from Kim, declaring the album to be a reflection of “the absolute craziness I feel around me right now”. The sleeve, tellingly, shows what appears to be her own silhouetted hand taking an iPhone selfie. So is that “craziness” epitomised by the perma-online bombardment of stuff we’re all been subjected to in the opening quarter of the 21st century? That very interconnectedness? Is she, essentially, a phone addict?

“I don’t like to be, but there’s a little bit too much compulsiveness about myself,” she admits.

And does that worry her?

“For sure, I could worry about that,” she smiles. “But it’s not in the Top Three. I am kind of worried about things like AI, though. Because already there are so many fake facts floating around. Most people don’t really pay that much attention to in-depth news, so things instantly become slogans, and having to decipher what has been doctored in a photo takes that to another level. We have to teach children in school how to defend themselves against that kind of thing.”

It feels like we’ve gone backwards, I suggest. Life has always been filled with worrying world events and disquieting disinformation, but until the advent of social media it felt much easier to separate the bullshit from the chaff. It must be an incredibly confusing era in which to grow up.

“Yeah, getting their news off Tik-Tok is the way they go,” she replies. “It’s a very, very strange moment. I like to say that I’m proud to have been born in the 1900s, although it sounds ancient when you say it that way.”

She did, in fact, turn seventy last April. By her own admission she’s “pretty shy” but she’s also charming and friendly, and passionate about music of many stripes. Some of the more spoken word sections on The Collective, I suggest, are reminiscent of The Shangri-Las. There are no candy stores or teenage motorbike crashes, but she definitely captures some of Mary Weiss’ style, that ineffable combination of the deadpan and the dramatic. Was that deliberate? Is she a fan?

“Definitely!” she nods. “A huge Shangri-Las fan. Some of their songs are these weird soap opera spoken word things, very melodramatic, which I think is kinda funny. I wasn’t thinking about them on this record, but it’s definitely something in my limited vocabulary of singing. They kind of changed the image of a girl group – of being more badass in a certain way.”

At the other end of the badass scale, I’m also intrigued by her oft-professed love of Karen Carpenter. As far back as 1990, ‘Tunic Song (For Karen)’ appeared on Sonic Youth’s album Goo. Kim’s excellent 2015 memoir, Girl In A Band, includes an open letter to Karen, keen to forge a personal connection (“Did you ever go running along the sand, feeling the ocean rush up between yr legs?”). So where did all this come from? Did she listen to the Carpenters as a young woman in 1970s LA before the punk bombshell hit?

“I didn’t!” admits Kim. “In the early 1970s, they were considered so establishment and uncool. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Thurston really turned me onto them. We got this reel of their videos from Tower and the production on those records is incredible. The way they used space… and her voice is just so soulful and sexy. It’s a disembodied voice in a sense, a voice almost apart from her. A voice that was just allowed to live. She expressed herself in a way that she couldn’t in the rest of her life. You can hear so much in that voice: sadness and sensualness. It’s fascinating.”

It’s the melancholy that gets me, I tell her. Even as a tiny kid, listening to my mum’s modest record collection, I was drawn to the sadness of The Carpenters. Rainy days and Mondays always get me down.

“Yeah, I love a melancholy voice!” she nods. “My dad had a lot of jazz, and I grew up listening to Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith.”

Her dad was the renowned UCLA sociologist who – in 1957, when Kim was four – published the first in-depth study of the social strata of US High Schools. Genuinely, our entire modern understanding of geeks and jocks comes from Calvin Wayne Gordon. It was also around this time that Kim began to feel the pull of her lifelong calling… to become a visual artist.

“I remember we had a print in our house of a cubist, abstract image that looked so much like my father,” she recalls. “When I first went to New York as an adult, I was in the Museum of Modern Art and I saw the same painting – and it was a Picasso! I had no idea. My father always had high cheekbones with long lines down that almost looked like they’d been sutured. With his hair in a pompadour. And the painting looked just like him.”

And her own artwork? In the book, she reveals her ambitions to become a visual artist began to bear fruit at the tender age of five.

“I remember so many things,” she says. “We’d make shawls and dye the fabric. In kindergarten, they showed us how to make elephants out of clay, and I was really good at it! So when I went to First Grade, they asked me to come back and show the younger kids how to do it. I did desert-scape paintings that I really like, too. I still have them. And some clay sculptures that I made as a teenager – I always took my art outside of school. I wasn’t very verbal, but I was good with my hands.”

The connection between family and art continues on The Collective. Lead single ‘Bye Bye’ – directed by Clara Balzary – stars Kim’s daughter Coco Gordon Moore as a youthful runaway raiding a food mart for the contents of the song’s shopping-list lyrics: “Toothpaste, brush, foundation, contact solution, mascara / Lip mask, eye mask, ear plugs / Travel shampoo, conditioner, eyeliner, dental floss”. It’s a terrific piece of downbeat mini-cinema, with the music providing a compulsive soundtrack.

“Clara originally wrote it as a short film for Coco,” explains Kim. “Then I ran into her and said I was coming up with ideas for videos. And she said ‘I could make this into a video for you’. So it was a happy coincidence, and she adapted the film to the song. And Coco looks great on film! She’s done a little bit of acting and I think she wants to do more. I’m making her appear in the next video…”

As with 2019 album No Home Record, the music is a collaboration with producer Justin Raisen, whose eclectic CV encompasses work with Charli XCX, John Cale, Sky Ferreira, Drake and Courtney Love.

“We did the last record together, and that worked,” says Kim. “I like rhythm – it inspires the lyrics and the singing, because I’m not a natural singer. So we talked about different periods of rap that I liked, from the 1980s and ‘90s, and Justin would come up with beats and send them over. I’d say ‘OK, I can do something with this’, and I’d put some dissonant guitar down and make a nice bed to sing over. Often things would just come out of my mouth. I like to improvise.

“Justin says ‘I make the beats, you bring your abstract poetry fucked-up shit!’,” she laughs. “And I’m always confident he’ll shape it and make it accessible.”

Her work as a visual artist, meanwhile, has progressed far beyond home-dyed shawls and clay elephants. Her work has been exhibited in London’s Gagosian Gallery, and at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. In Summer 2023, a new collection at New York’s 303 Gallery seemed to foreshadow some of the themes of The Collective, featuring abstract paintings with iPhone-shaped holes cut into their canvases. Do the music and the visual art of Kim Gordon, I wonder, feel like entirely different disciplines? Or is there – ahem – a connectedness between her work in both fields?

“They are different disciplines,” she says. “And making art is much harder. But really, it’s all just work. Just different forms of expression.”

Does she treat that work as an office job, then? I’ve met a few musicians who enjoy the discipline of the 9-to-5, even if they’re noodling on a guitar rather than dealing with round-robin e-mails from human resources.

“Oh God, no!” she grimaces. “I pick up my guitar and just play when I feel like it. I finished making this record last May, so it’s been a long wait. But getting ready for it to come out, and having all this activity… it kind of organises my brain and gives me ideas for other things. It’s like ‘Wake up, you’ve been sleeping!’ It makes you feel alive.”

It sounds like the next album might already be in the offing…

“No,” she laughs. “Well, maybe in Justin’s mind! The thing is, I really appreciate that people want to talk to me. And I like it when I get to meet people like you and have a nice conversation. But all the work to promote a record also kind of makes me not want to do it! So after this, I’ll probably want to do something solitary. I’ll go into my study, or I’ll write.”

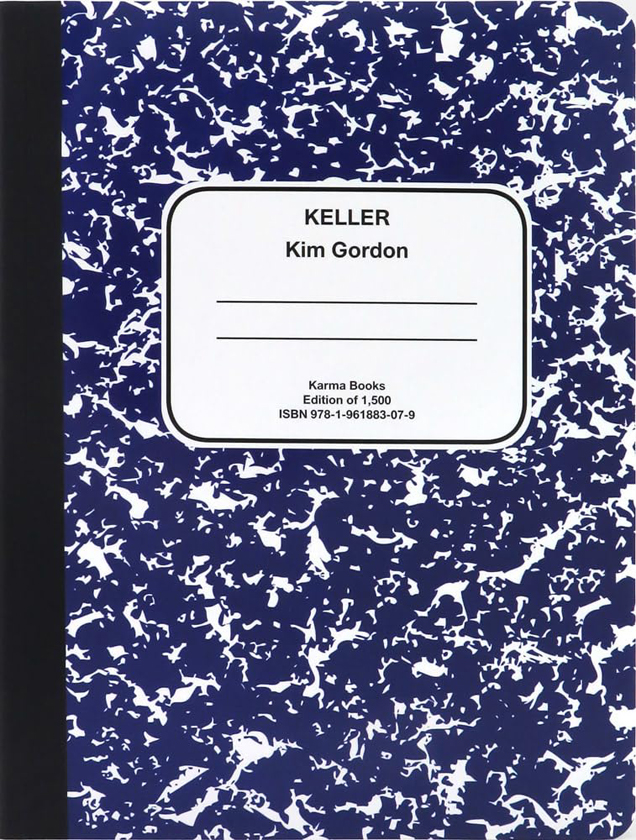

Speaking of which, another book is imminent, with further family connections. In Girl In A Band she discussed her relationship with her older brother, Keller. An accomplished scholar, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his twenties and later moved into an assisted living home. He died in February 2023, and Kim’s next book – simply titled Keller – is intended as a tribute to him.

“It’s more of an art book,” she explains. “He was an Elizabethan scholar, and a poet who wrote sonnets. He studied Greek and Latin. And he had notebooks that are basically scrawls, they almost look like Cy Twombly paintings. But every now and then you can see words – ‘Adonis’ or ‘Venus’ – and then he’d draw these funny pictures of a face.

“It’s funny, because the only clay object he ever made was this funny head in Grade School. I guess it was a kind of self-portrait. But these drawings look like that head. So I wrote some text about him, and there are pictures too.”

Girl In A Band suggests their relationship, at least during childhood, was challenging and complex. Were they in a good place towards the end of Keller’s life?

“Yeah, I’d spent a good six or seven months with him,” she nods. “He had skin cancer, with squamous tumours on his head because he would sit outside the place he lived in, smoking cigarettes in the sun, and he wouldn’t wear sunscreen. So my good friend from High School and I took him for his treatments.

“He didn’t die from the cancer. It was weird, he was just found on the floor like he’d fallen out of bed. But I got to spend a lot of time with him in the car – and he was very funny. I’d put on Neil Young songs, and he’d sing out of tune! He was always flirting with the nurses – very inappropriately, sometimes – or he could be grumpy and in a bad mood. But, for the most part, he was incredibly appreciative of us, and very charming. So it’s good that I had that time with him.”

And with that, it’s time to close the fizzling windows on our respective screens. But good grief, Charlie Brown – it’s been an honour.

The Collective is available here:

https://kimgordon.bandcamp.com/album/the-collective

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen