In September 1987, my English teacher Mr Harrison – a brilliant, inspirational man who could also pull off a passable Les Dawson impersonation – set our newly-assembled GCSE class a creative writing task. He provided us with a title for a short essay (“What A Stupid Mistake”) and left the actual content of the composition to our own imaginations. We could, he insisted, write about anything we liked, providing that a monumental “stupid mistake” was incorporated somewhere along the line. Then he put on his glasses and said “knickers, knackers, knockers” in a Teesside accent with a gurning, scrunched-up face.

I was 14 years old, brimming with optimism, insatiable joie de vivre and a surfeit of unbridled, youthful enthusiasm. What else would I write about other than the devastating after-effects of a global thermonuclear conflict? By September 1987 I had lived through four solid years of nuclear paranoia, a personal childhood obsession that bordered on the phobic. And – despite glasnost, perestroika and the other reforming efforts of Mikhail Gorbachev – I was still clearly a bit twitchy about the prospect of “the balloon going up”.

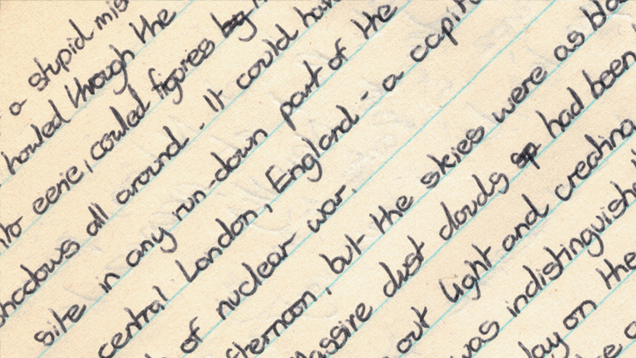

I discovered my essay last month in a cardboard box in the loft, and have replicated it in full below. And Good God… at this stage in my life, I hadn’t even seen Threads…

WHAT A STUPID MISTAKE

The wind howled through the towering columns of rubble, sculpted into eerie, cowled figures that cast deep and dark shadows all around. It could have been any run-down building site in any run-down part of the country, but this was central London, England – a capital city facing the aftermath of nuclear war.

It was mid-afternoon, but the skies were as black as if it were night. Massive dust clouds had been thrown into the atmosphere, blocking out light and creating an eerie twilight world where night was indistinguishable from day. Several inches of snow already lay on the ground – with no light or heat it seemed a new Ice Age had settled upon the northern hemisphere and the driving white flakes attacked the gnarled remains of once-proud landmarks. Nelson’s Column, the Houses of Parliament, all were now gone, and in their place were nothing more than towers of crumbled masonry.

Elsewhere something stirred – pockets of civilisation still remained, small groups of men and women lived out a futile existence some nine or ten feet below the ground. But this was no more than a living corpse, an insult to nature as it stumbled, frail and bleeding to the ground and died. Rats scurried to and fro and his body would be quickly and greedily devoured.

This was the scene all over the country, in fact over most of the globe, where huge cities lay destroyed and devastated, their smoking remains sprawled for miles. Even on the outskirts, and in the country, few houses still stood, cattle lay dead and bloated and people were dead and dying, their bodies riddled with horrific wounds and radiation. All was still, and all was silent.

And yet, although there was no-one to ask it, and no-one to answer it, a question was forming. And the question was this – why? Why had we allowed it to happen? A handful of men had destroyed the planet, and now only a handful of men were left to rebuild it.

What a stupid mistake.

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen