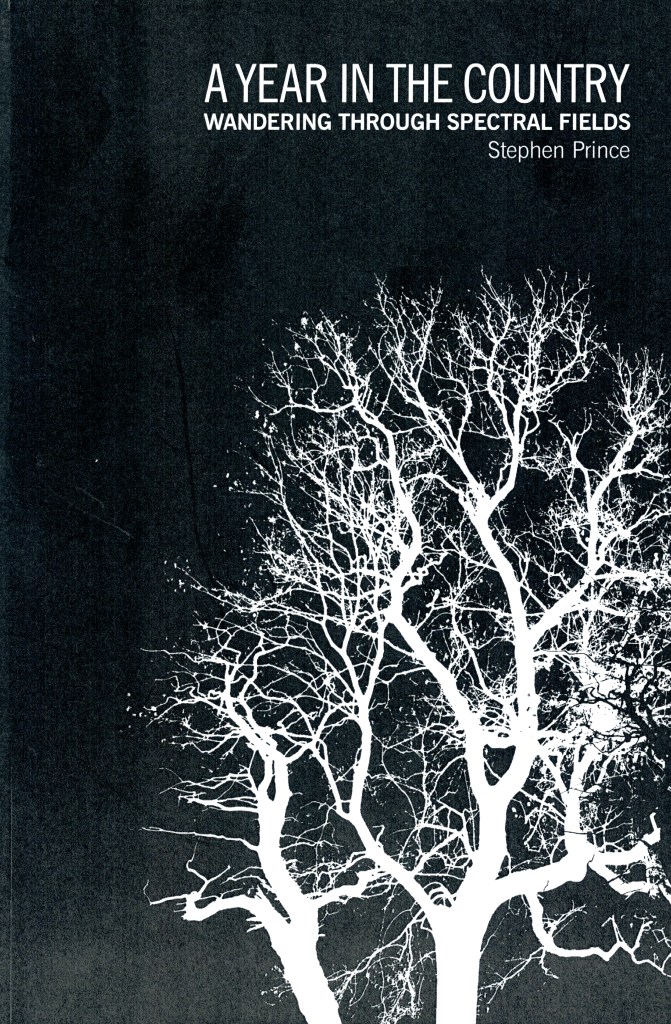

Since 2014, Stephen Prince’s impressively comprehensive multi-media project A Year In The Country has exploring and documenting some of the lesser-trodden pathways between pastoral folk music and radiophonic electronica, as well as actively contributing to these genres with a succession of hugely enjoyable musical releases. The 2018 book Wandering Spectral Fields has hewn considerable dents in many a bank balance (including mine) with lovingly-written essays unravelling the tangled connections that bind an underappreciated welter of late 1960s/early 1970s acid-folk with the 21st century hauntology movement; via Kate Bush, Bagpuss, the films of Peter Strickland, Sapphire and Steel and the work of the Telegraph Pole Appreciation Society. Eighteen months on, my Amazon Wishlist is still groaning under the weight of a myriad of Stephen’s heartfelt recommendations.

With a new book – Straying From The Pathways – in the offing, and a new album – Echoes and Reverberations – freshly released, it seemed like an apposite moment to speak with Stephen, and discuss the lifestyle changes that led to A Year In The Country‘s inception, the childhood memories that have fuelled his explorations, and some of the music, TV and film that he has found to be especially affecting and inspiring…

Bob: Can you tell me how you started the whole Year In The Country project, and what inspired you to do so?

Stephen: For a long time I’d been working in often very city-based, left-of-centre pop culture and also living in quite central urban areas. Without consciously realising it, after finishing a particularly big creative project, I found myself being drawn to more rural areas. Perhaps I found myself wanting a quieter pace of life, a sense of space and so on.

I listened to a friend’s copy of the compilation album Gather in the Mushrooms: The British Acid Folk Underground 1968-1974, compiled by Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne. I was wandering through a dimly-lit, post-industrial part of an inner city when I first heard Trader Horne’s “Morning Way” on the album, a song which begins with “Dreaming strands of nightmare are sticking to my feet” and I thought… this isn’t like any form of folk that I’ve heard before. I think it opened up something in my mind, and is part of what led me to start A Year In The Country in 2014, and its explorations of the flipsides of folk and pastoral culture.

Also, although again I’m not sure how conscious it was, I began to want to find some kind of catharsis for the shadows of Cold War dread that I’d been carrying around since childhood, something which for myself – because I was living in the countryside when I learnt more fully about the potential realities of the Cold War – was curiously linked with rural areas and ways of living.

Beyond Gather in the Mushrooms, I didn’t really know about what has come to be known as hauntology, and the undercurrents of folk/pastoral culture, when I started thinking about and planning A Year In The Country. Maybe there was something in the air, as looking back it was a time when, unbeknownst to me, that culture seemed to start flourishing and finding an audience. Part of A Year In The Country has been about myself exploring, documenting and discovering this loosely interconnected culture, and the people who work in it.

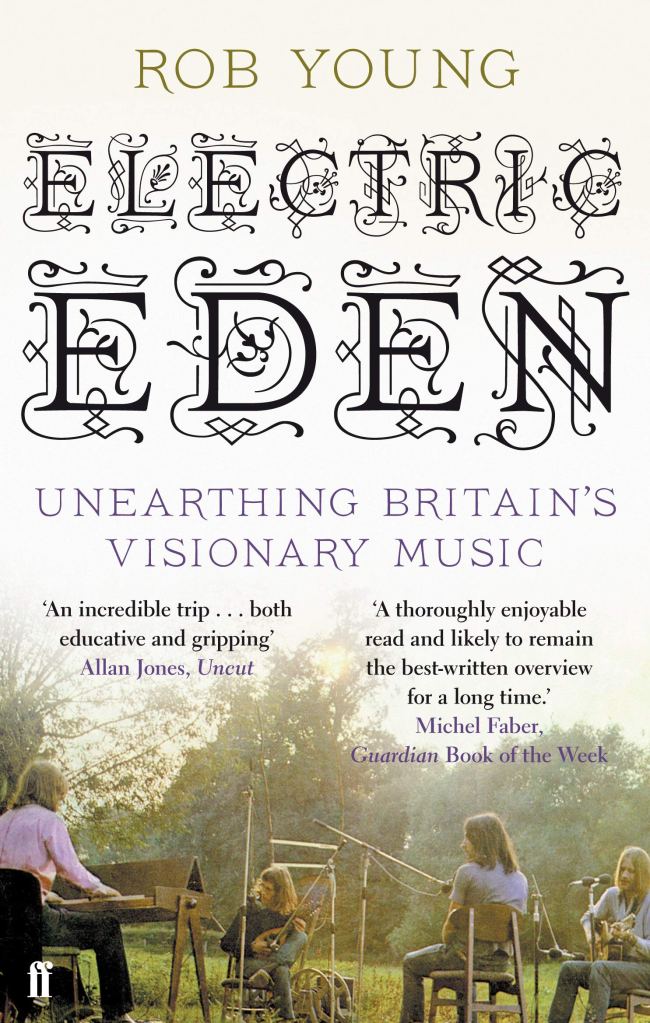

Somehow or other, I wandered from Gather in the Mushrooms to the underground/left field folk band The Owl Service; hauntology, Ghost Box Records and in particular, initially, the Broadcast and The Focus Group Investigate Witch Cults of the Radio Age album and the time-out-of-joint of The Advisory Circle’s track “And The Cuckoo Comes“; Trunk Records and The Wicker Man soundtrack; the cosmic aquatic folklore of Jane Weaver Septième Soeur’s The Fallen By Watch Bird, which was in part inspired by the modern-day fairy tales of the Czech New Wave, which I also began to explore; and Rob Young’s Electric Eden book, which takes a wide-reaching look at the sometimes hidden landscapes of folk and pastoral music and culture. Some of those things I knew about already, but without realising that was what I was doing, I began to link these, at times, loosely connected things together… to form lines in the cultural landscape, as it were.

In some ways I wanted to create a website or project that I would want to visit. One that explored all of the above and hopefully could help to draw lines of connection between them.

Did you always foresee it as the multi-media experience that it has become, or – at the outset – did you simply intend to do a bit of gentle blogging?

Ah, a bit of gentle blogging may have been a bit easier!

From week one of A Year In The Country, I began releasing prints, badge sets and so on, and I always planned and hoped that I would put out music. Which I began to do in the first year.

Along with the more directly cultural sides of work, I’m very much interested in the practicalities of releasing things into the world. It’s all part and parcel of the same thing to me. For me, all the different areas of A Year In The Country – the website, the books, the music, the prints, the artwork, the making of the physical releases, the practical distribution aspects, the theoretical sides of things and so on – intertwine.

In terms of releasing books, I was particularly intrigued by the last chapter of Rob Young’s book Electric Eden, called “Toward the Unknown Region”. That chapter discusses the likes of Ghost Box Records and the outer fringes of pastoral/folk culture and, in part, seems to capture a particular spectral/hauntological atmosphere, the sense of parallel world creation that often occurs in hauntological and related folk work. It also linked together (or at least showed that they can sit side-by-side) certain aspects of hauntology and the fringes of folk culture, alongside discussing how some of folk/pastoral culture has changed and wandered off down new and sometimes surprising pathways.

I think I thought to myself, about that chapter, “I want some more of that!” and I hoped, although again maybe not all that consciously, that at some point I would put together a book that continued exploring the pathways that “Toward the Unknown Region” had begun to walk down, as well as bringing together some of the other cultural reference points that I’d found myself wandering amongst.

Again, basically, at heart I wanted to put work out into the world that I would enjoy myself, and that I found myself looking for.

Did the founding of A Year In The Country begin with a genuine lifestyle change… you actually moved into the countryside, didn’t you? How did you find this affected your state of mind?

Yes, I had moved to the countryside before the founding of A Year In The Country, and that’s when planning for it began in earnest.

Although things have changed in terms of rural access to culture – due to internet connections, expanded mail order, and so on – there is possibly still a sense that there’s more space for your mind to wander, with fewer cultural distractions. Even something as simple as there being fewer flyposters or advertising hoardings makes a difference. There’s also just a different pace of life, a slower, potentially more contemplative one. Although at this point, I think it would be good to point out that I’m not trying to say that either the countryside or cities are good or bad, there are positives and negatives with both.

I think looking back, I had a sense that pop culture, even in its more leftfield and alternative aspects, had become a very busy, crowded and heavily-harvested area of culture.

In contrast, and accompanying that literal sense of space, there also seemed to be more space within the undercurrents of folk/pastoral culture and where they meet and intertwine with hauntology. At that point they hadn’t been all that intensively explored. They seemed to be at a remove from the spotlights of attention that pop culture is routinely subject to, and that accompanying sense of business or cultural hurly burly.

So, essentially, the countryside gave me and my mind space to rest and wander. The different character, rhythms and so on of folk and pastoral culture began to make more sense once I lived in the countryside, and I would often find myself reflecting on the differences between it and more urban culture as I was wandering across the fields.

Is the desire to revert to a simpler, more bucolic lifestyle growing, do you think? A lot of people (including me) seem to find 21st century life rather daunting and anxious…

There’s a sense that it may be growing, although that’s based more on anecdotal observation than in-depth study.

Perhaps the way that people are drawn to it is an expression of wanting to find some respite from the modern world. If you look back to the 1970s, a time when some people were also drawn to bucolic and folk culture, that was a time when society in the UK was going through a period of uncertainty and turbulence, and bucolic ways of life may have offered an escape from that. Parallels could be drawn between then and now.

Although curiously and conversely, within hauntology and folk culture, being drawn to the bucolic often seems to be accompanied by exploring an unsettled flipside to it. Possibly due to a related and interconnected wish to, consciously or not, find a way of expressing and making sense of contemporary turbulent times and the connected sense of anxiety.

Connected to this, some of the reasons for the current interest in wyrd folk, otherly pastoralism and hauntology could be, as I mentioned above, that they give people the space to create imagined parallel worlds or planes of existence, ones which variously allow for a break from the contemporary anxieties, worries and day-to-day life. It could also be because humans as a species seem to be fascinated by and have a need to tell stories, spin yarns and create waking dreamscapes.

Related to 21st century life being daunting and anxious, the level of input and output of culture today can be potentially overwhelming. If I take myself as an example, I grew up in a time when there was a scarcity of, and restricted access to, more leftfield culture and some popular culture. You very much had to seek it out – which is almost the polar opposite to today.

Back then, there were only three – then four – television channels in the UK, one main weekly pop music television show, three or so weekly alternative music magazines, and – until the 1980s and the more widespread use of home video recorders – you couldn’t easily watch a broad range of films at home. And the numbers and types of books and albums you could read or listen to were quite limited by your personal budget, and what could be found in the local library, or in book and record shops.

Now there is an almost unlimited, constantly changing deluge of culture, available digitally and in other forms and often – particularly in the case of music – inexpensive via streaming services. I wonder if my brain, and those of others of my generation, is in some way still physically wired to times of cultural scarcity, and whether the way things are now can induce a sense of “not keeping up” – of there just literally, potentially, being too much input.

Also, growing up in a time of cultural scarcity can make you feel you have to pay attention to all and any culture when it does pop up. In my younger years, if I saw a rare and interesting single in a charity shop, I’d think that I would have to buy it and listen to it, as I might never see it again. That’s no longer the case, but perhaps some of that mentality lingers on in modern times. If that’s how you grew up, the ubiquity of access to nearly all culture can lead to a potential sense of being overwhelmed.

Accompanying which, there can be a daunting pace of change; there are theories that suggest that the development of human ideas, science, technology and creativity only really took off once there was a certain critical mass of people who weren’t living in small isolated groups anymore, meaning ideas could be more easily exchanged, passed around, developed and so on. To a degree, modern communication methods, travel, and information storage and retrieval may be supercharging that process, in a way that outpaces the human brain’s ability to process it. And so it can seem like the ground is constantly shifting under your feet, which doesn’t necessarily lend itself to not being anxious.

There is also economic and unemployment uncertainty, and the potentially related fast pace of change; that idea of a trade for life, and knowing that how you make a living now will be the same in a few years, let alone decades, has – to a large degree – disappeared. That applies in wider life and also within creative work, where traditional funding methods and routes have been largely swept away, and we live and work in a constantly changing cultural and economic environment.

Of course, at the same time I’m wary of just being “Bah, humbug, in my day it was all green fields, just three TV channels and an easier way of life.” The world changes and moves on and, to state the obvious, there are often pros and cons to all such changes.

Does the music, art and literature involved with the movement give you a connection to your childhood memories? Rather nebulous memories of being very young in the 1970s seem to be a huge part of all this…

I think it maybe did more so in the earlier days of A Year In The Country, which had the shadows and memories of Cold War dread as something of an underlying theme. As hauntological work often draws from such things, and a sense of unsettledness in 1970s culture, that provided a connection to my childhood.

There were science fiction television series that I only saw glimpses of in the 1970s, dystopian science fiction and horror novels and films that I was drawn to, but which I was maybe too young to fully understand… or that I just saw covers of, and created my own stories around them. All of that became a kind of personal dreamscape from which A Year In The Country partly draws – it’s not always the actual culture, but more a half-remembered or misremembered, sometimes never fully-known version of it from my childhood.

That feeling of a childhood tainted by the terror of nuclear war (or even just the general unease/melancholy of 1970s culture and society) has become such a potent one. Do you think there was something unique about that period that produced those feelings, and inspired the wave of artists and musicians that have mined it for inspiration?

That period has a number of characteristics which may have made it such an inspiration for hauntological work: although this is a broad generalisation, the late 1960s, tipping over into the 1970s, can be characterised as a point in UK/Western society when post-war and hippie optimism began to crumble, and – throughout the 1970s and early 1980s – society entered a period of economic and societal disturbance and uncertainty. There is a sense that the late 1960s to late 1970s was “a time before the fall”, and that – consciously or not – it represents a time when post-war progressive intentions and futures were fought for and lost. That, and the culture produced around that time, has become a source for, and come to represent, a sense of hauntological melancholia.

At the same time, in the 1970s, there seemed to be areas of freedom within, for example, large-scale mainstream cultural institutions such as the BBC, which allowed for the creation of at times very exploratory and left-of-centre culture. Penda’s Fen, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and so on. To a degree that continued into the 1980s, although looking back, by that point, they seemed more like flashes of rearguard resistance.

Given that we were so uneasy during our childhoods, why do you think we now often find comfort in those memories?

That’s an interesting question. Perhaps if you pull the monsters out from under the bed and shine a light on them, it helps to – if not neuter them – then at least to weaken their power.

Although that sense of unsettledness doesn’t just draw from the Cold War, that particular conflict was a strange thing to live through: a form of politics and foreign policy based on the complete destruction of global civilisation, and the creation of weapons to do that. It could be seen as a kind of collective madness in a way. To a degree, within mainstream society, the reality of living through it and the potentially harmful psychological effects aren’t really acknowledged, and that whole period has been sort of swept under the carpet of history and become just another story from past decades. Rather than something that directly affected people who are still alive.

So perhaps the hauntological exploring of those uneasy childhood memories acts as form of balm, a way of easing that unsettledness by creating a space where they can be examined.

I’m intrigued by the new A Year In The Country musical release – Echoes and Reverberations. These are recordings inspired by film and TV locations, both real and imaginary. I actually went to two 1970s Doctor Who locations recently… Aldbourne, which doubled as “Devil’s End” in The Daemons, and East Hagbourne, transformed into “Devesham” for The Android Invasion. And I couldn’t look around either village without thinking of the terrible events that occurred there… but, of course, they didn’t. And the pub in Aldbourne has blurred reality further by placing a “Cloven Hoof” sign outside the front door… when, in actuality, it’s called The Blue Boar. Do TV and film locations almost almost become two places, one real and one fictional?

It sounds like you’ve been doing some interesting wandering…

You could consider such places to have two realities; a surface and an imaginary one, or a literal one and one which exists in the mind.

That sense of places having an alternate reality is one of the main themes of the Echoes And Reverberations album; it’s an exploration of the way that places become layered with the stories and atmosphere of the films and television programmes which were recorded there – with each track being by a different contributor and focusing on a particular location and film or television programme.

Sometimes that layering may be expressed overtly, if an area has become well-known as being a particular film or TV location and a related tourist industry has built up around it, or it may be more of a personal, private thing.

I wanted the album to explore how these places can become sources of personal and cultural inspiration, and also locations for a form of modern-day cultural pilgrimage. Partly as a marker of such pilgrimages, each track contains field recordings from such journeys.

The layering of different realities and stories in a place is very much an abstract and, as I just said, often a very personal thing. And so, as I wrote in the album’s accompanying text, the tracks, their themes and the field recordings are a “seeking of the spectral will-o’-the-wisps of locations imagined or often hidden flipsides.”

It is, in part, also an exploration of the themes from these real and imaginary film and television programmes, from “apocalyptic tales to never-were documentaries and phantasmagorical government-commissioned instructional films via stories of conflicting mystical forces of the past and present, scientific experiments gone wrong and unleashed on the world, the discovery of buried ancient objects and the reawakening of their malignant alien influence, progressive struggles in a world of hidebound rural tradition and the once optimism of post-war new town modernism.”

More specifically, that takes in such hauntological and otherly-pastoral touchstones as Penda’s Fen and Quatermass, via Survivors, and onto the likes of 1991 science fiction series Chimera, and period drama Flambards.

On the album there are 10 tracks and accompanying text by Grey Frequency, Pulselovers, Dom Cooper, Listening Center, Howlround, A Year In The Country, Sproatly Smith, Field Lines Cartographer, Depatterning and The Heartwood Institute. Musically, as with the majority of the themed A Year In The Country compilation albums, it takes in quite a wide range of musical styles, from radiophonic electronica to its more contemporary counterparts, shades of acid/psych folk, tape machine manipulation and so on… which could be seen as an example of the interweaving of the undercurrents of folk and hauntological work.

And as you say, some of the tracks are inspired by imaginary film and television locations. For some people, places have become imbued with alternate realities and atmospheres related to stories that only exist in their own imaginations. In this sense the album also loosely interconnects with other work in hauntological areas/the undercurrents of folk, which also creates soundtracks to imaginary films and television, such as The Book of the Lost, Tales from the Black Meadow and The Equestrian Vortex, or the A Year In The Country-released The Shildam Hall Tapes and The Corn Mother.

Have you gone on similar quests to find TV and film locations? How did they make you feel?

Sometimes I have more gone on personal quests related to my own past experiences, rather than specifically to a particular filming location.

For example, during the first year that I moved to the countryside I went out photographing a lot, taking the images I would use in the artwork, prints and albums in the first year of A Year In The Country. At the end of that year, to the day, I set off on a journey to take photographs in the small country village where, as a child, I first discovered and experienced Cold War dread, and dystopian science fiction, and saw glimpses of the children’s television drama series Noah’s Castle, which showed society collapsing due to hyperinflation. All of which fed into A Year In The Country.

Prior to that year, I hadn’t visited for a number of decades and it was a curious thing to wander amongst and revisit my own past via this literal landscape, one which had informed the mental landscape that created some of the roots that became A Year In The Country. As you suggested earlier, at such times it is almost as though places have more than one reality, and their different layers and realities intertwine.

Completely coincidentally, on the train route back, an arthouse cinema was showing Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape and an episode of Beasts. Not something you expect to see every day or even once a year at the cinema, and so I stopped off on the way home to watch them, which felt like something of a cinematic/cathode ray rounding of the circle of that first behind-the-scenes year of A Year In The Country.

More directly related to filming locations, the first time I visited Portmeirion, which as you probably know was the location where much of The Prisoner was shot, I could tell that the younger, subconscious me who first saw The Prisoner was thrilled to be there. It was strange seeing the place in full colour, and in such real-world high-definition… I had first seen The Prisoner on a black and white television, and I think that memory of it had lingered with me. I think I had expected it to be more like a film-set facade, but the buildings were functional and very three-dimensional.

However, it was not so much the actual village of Portmeirion that seemed to capture a sense of The Prisoner for me, but rather a deserted beach area next to it that I came upon by accident, and which summoned up endless visions of No. 6 trying to escape before being recaptured by the Rover.

Perhaps the beach and its more abstract connection to The Prisoner allowed my mind and imagination to wander more. Whereas the buildings and giant chessboard in Portmeirion village were great to see, they didn’t allow for that mental space so much, as they were a more literal representation of the series and my memories of it.

All of this feeds into the new A Year In The Country book, too…

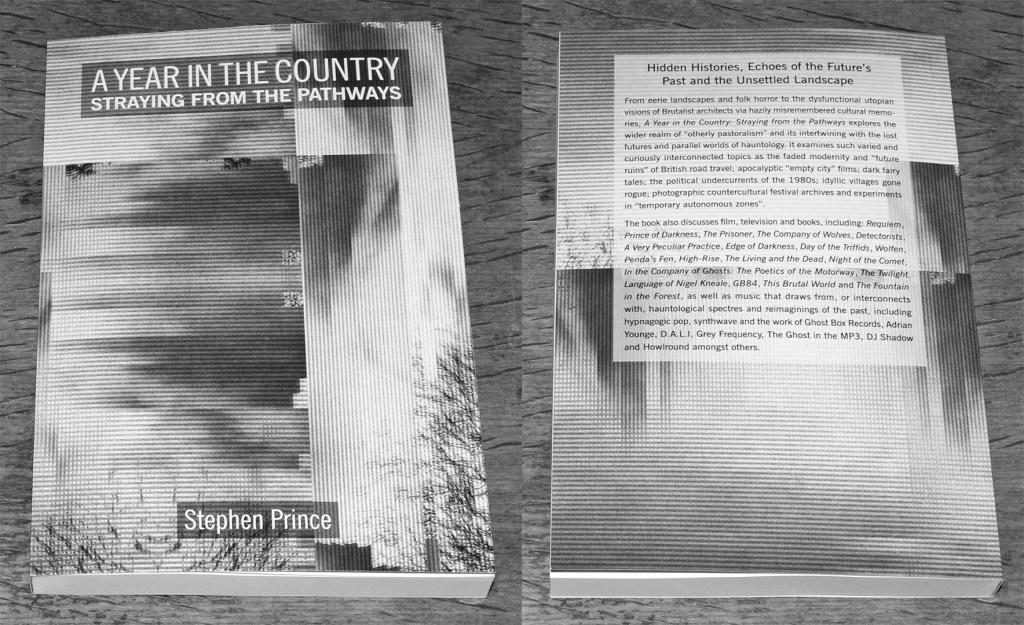

Yes, A Year in the Country: Straying from the Pathways, which is released on 8th October 2019.

As with A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields, Straying from the Pathways explores the undercurrents of folk/pastoral culture and where it meets and intertwines with the lost futures and parallel worlds of hauntology, including a fair few of the themes we’ve discussed above.

It includes writing about some of the core culture from such things while, as I say in the introduction, I also wanted to push back the boundaries and look elsewhere for where hauntological-esque spectres, lost futures and re-imagined echoes of the past might be found.

To semi-quote from the cover, it wanders amongst eerie landscapes, folk horror, the dysfunctional utopian visions of Brutalist architects and hazily misremembered cultural memories, taking in the likes of the faded modernity and “future ruins” of British road travel, apocalyptic “empty city” films, dark fairy tales, the political undercurrents of the 1980s and idyllic villages gone rogue.

So, in Straying from the Pathways you’ll find writing on film, television and books including John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness, Halloween III, The Company of Wolves, Penda’s Fen, the Texte und Töne-published book The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale, The Prisoner, GB84, Edge of Darkness, along with music that draws from and interconnects with hauntological spectres and re-imaginings of the past including synthwave, hypnagogic pop, The Ghost in the MP3, Howlround, Grey Frequency and Ghost Box Records… amongst others.

Thanks so much to Stephen for such a thoughtful and fascinating interview. And for all your Year In The Country requirements:

https://ayearinthecountry.co.uk