(This feature first published in Fortean Times No 449, dated October 2024)

HARE TODAY

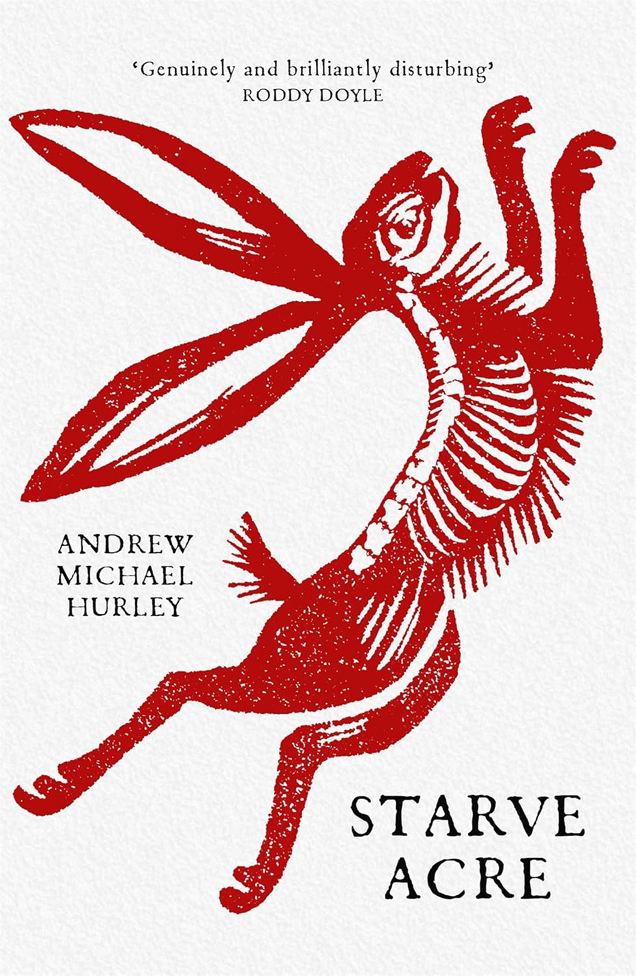

ANDREW MICHAEL HURLEY’s 2019 novel Starve Acre was widely acclaimed for using elements of Folk Horror to explore the trauma of grief, and a new film adaptation – directed by DANIEL KOKOTAJLO – has lost none of the book’s potency. BOB FISCHER meets both men to discuss hares, witchcraft and the abiding influence of Nigel Kneale

“I’m fascinated by the folklore of hares,” says Andrew Michael Hurley. “There are lots of stories about witches transforming into hares to escape farmers – including one local to me. In a place called Woodplumpton, just outside Preston, there’s a witch called Meg Shelton buried in unconsecrated ground beneath an enormous granite boulder. The story goes that, after she’d first been buried, she climbed out of the plot and was seen wandering around the village, so they buried again head down and put a huge rock on top of the grave.

“There are numerous stories about her destroying lifestock and spoiling the milk, then escaping from the farmers by shapeshifting into a hare and darting off across the fields. So I think that story was probably in my mind when I was thinking of hares as folkloric figures. They’re mysterious animals: big, muscular, sinewy, long-legged weird things that you don’t see very often.”

We’re discussing Starve Acre. Andrew’s acclaimed novel of that title was published in October 2019, and focuses on the all-consuming grief of Richard and Juliette, a young 1970s couple whose new life in Richard’s remote Yorkshire childhood home is torn apart by the death of their five-year-old son, Ewan. Richard, an archaeologist, becomes obsessed with the local legend of a hanging tree in the house’s barren grounds, and also with the associated folklore of Jack Grey: a malevolent nature spirit made manifest in the twitching ears of a distinctly unearthly hare.

Further inspiration, explains Andrew, came from his chance discovery of the title itself.

“This is how exciting my research is!” he laughs. “I first saw the name Starve Acre in a book called English Field Names. I was leafing through and it kept recurring. There was a field in Yorkshire called Starve Acre, and others around the country, too. I began to wonder what had happened in those fields for them to acquire that name, and to think about some of the folklore that might be associated with them.

“For some reason, nothing grew in those places. And that ‘for some reason’ really intrigued me, and that’s where the story came from.”

The book has now been adapted for the big screen by director Daniel Kokotajlo, whose film does a evocative job of preserving the book’s sense of windswept isolation and a sense of very rural weirdness. Both Andrew and Daniel join me in adjacent windows via the mystical powers of Zoom, and are clearly filled with admiration for each other’s work.

“I read the book before it came out,” says Daniel. “I got hold of a promo copy and I loved it, and we started talking about a film version very early on. I was struck by Andrew’s approach to the mythic, symbolic elements in the story. It was also unashamedly an ode to old British storytelling – it reminded me of MR James And Robert Aickman, but with a focus on the emotions of the relationship between a grieving couple. It was exciting to me, a genuinely rare opportunity to make something strange and uncanny and unidentifiable.

“Grief is a subject I’m preoccupied with, and that’s something I felt Andrew tackled in an interesting way. There’s a thin line between hope and horror when it comes to grief. People can find comfort in spirituality and religion, and that can be a genuine source of relief, but it can also have a crazy effect on the psyche.”

The turmoil in Richard and Juliette’s relationship reflects this conflict perfectly. While her husband throws himself obsessively into excavating Starve Acre itself, hoping to unearth the fabled hanging tree, Juliette deals with her grief by embracing the supernatural. And although Jack Grey is ostensibly a malevolent figure, she begins to find his presence worryingly comforting. Richard, however, is haunted by childhood memories of his own father conducting some particularly alarming research into the local folklore.

Did either Andrew or Daniel bring their own memories of childhood nightmares to the story, I wonder? Do they remember hares hopping into their bedrooms, or their own equivalent of Jack Grey poking his spindly talons around the corner of the wardrobe door?

“I had a very strict religious upbringing,” says Daniel, whose 2018 debut feature Apostasy explores his childhood as a devout Jehovah’s Witness. “So I didn’t really have folkloric or Pagan ideas around in the house. I had a fear of the devil and of demons messing with me, but that was always in a religious context. I was very scared of the devil. So although I was always into horror films, every so often I would become plagued by guilt and would purge them all. I’d give them away to the other kids at school. It was a genuine fear, it would fade away then come back every couple of months.

“But Andrew… the word Jack is a common name for these kinds of figures, isn’t it? I recently read the novelisation of Blood on Satan’s Claw, and there’s a section in that where they talk about Jack being a very common name for the Green Man”.

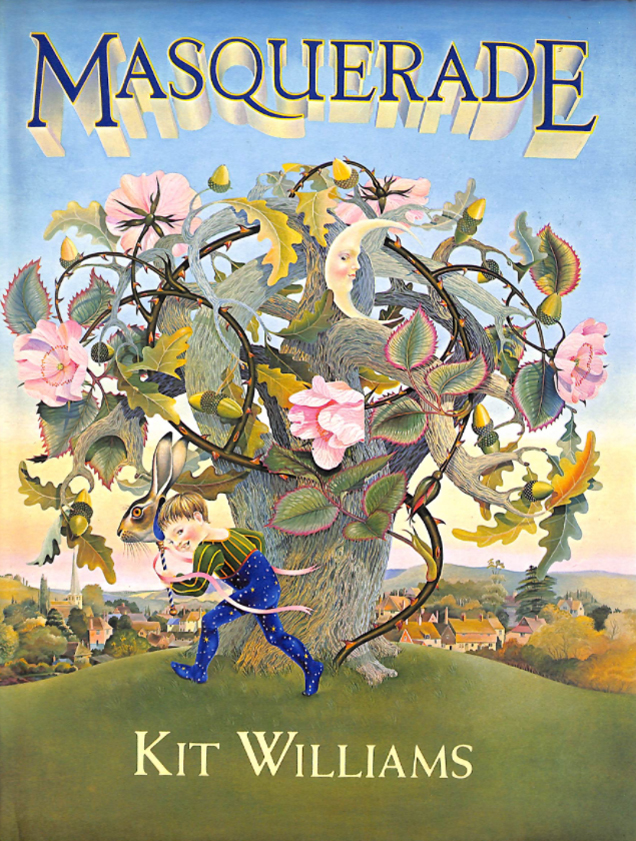

“Yeah, the Jack in the Green,” replies Andrew. “I don’t know if you remember the 1970s book Masquerade, by Kit Williams? The hare in Masquerade is called Jack as well, so that’s probably where I got the name from. I just wanted it to sound authentic, although the actual entity in Starve Acre is pretty much my invention.”

What is clear is that both men have used their Northern bringing as a profound inspiration. Both were raised on the other side of the Pennines to Starve Acre’s Yorkshire setting, but story is infused with the black melancholy of the moorland that sweeps across the north of England.

“All my novels start with the peculiarity of place,” nods Andrew. “And there’s a unique topography to the north of England: I can’t think of another place in the country where the urban and the rural meet so abruptly. I’m thinking of Blackburn, Burnley, Accrington, looking towards Pendle… these communities butting up really close to the moors. That emptiness, that expanse of wilderness is right there on your doorstep.

“And there are so many stories. It feels like there’s a lot of history layered into the soil. Not only about the Pendle witches, but the devil as well. Lancashire was a hotbed of Catholicism but also rampant Paganism and Satanism, and the clash of those things is really interesting.”

“Landscape is important for me, too,” says Daniel. “We shot in Nidderdale, not far from Harrogate. We found a house on a slope that had an eeriness about it – you couldn’t see the horizon, which I loved. Just a boggy slope of a field with nothing growing there. It felt just right.”

The wintry feel is important too, I suggest. Some Folk Horror stories are steeped in the hallucinogenic strangeness of a baking hot midsummer, but Starve Acre’s nightmares are firmly rooted in the unrelenting mud, fog and snow of a particularly filthy moorland winter.

“It’s about the transition out of that,” nods Andrew. “The story begins in winter, and it’s a winter that seemingly doesn’t want to end. But eventually it does, and I was really interested in what that transition to spring might offer to the characters in terms of their grief. A sense of hope, perhaps? But I was also interested in the actual process of things, and in the novel one of the things I tried to do was reverse that natural process quite a lot. So things go backwards that should go forwards! The unnaturalness of the landscape somehow mirrors the unnaturalness of Ewan’s untimely death. No child should die at five years old, and that seemed to reflect the weirdness of the place itself.”

The real-life reversal of natural processes actually caused problems on the shoot, with filming frequently put at the mercy of some typically mercurial Yorkshire weather.

“We shot the film in late winter and early spring, with the hope of capturing the feel of winter at the beginning of the shoot,” recalls Daniel. “But in the first week, we had a heatwave – it was 30 degrees, and we had to get snow machines! I was so embarrassed. Then, in the second week, we were shooting indoors with the house blacked out and someone in the crew said ‘Look outside!’. There was a snowstorm, so we ran out and re-shot two scenes in half an hour.”

Daniel is quick to praise the contribution of his two lead actors, both of whom bring touching performances to the film – as well as some impeccable fantasy credentials. Playing Juliette is Morfydd Clark, fresh from her starring role as Galadriel in Amazon Prime’s globe-straddling Tolkien adaptation, The Rings of Power. While Richard is played by the eleventh Doctor Who himself, Matt Smith.

“They were both super easy to work with and very creative,” says Daniel. “They brought loads to it. I’d just seen Morfydd in [2019 horror film] Saint Maud before working on this and I was very excited to work with her. I’d heard she was into folklore and gothic material, and we spoke about the idea of trauma being passed down through myth. She got that straight away.

“And the same with Matt. He’d just come off shooting [HBO fantasy series] House of the Dragon, and he was keen to work on location. We spoke about the new wave of archaeologists in the 1970s, all influenced by hippy culture and the social sciences. They had long hair and were getting their hands dirty! They weren’t wearing dicky bows at universities, they were freer – which is what Matt brought to the film. Maybe originally Richard was a little stiffer, but Matt made him more authentic.”

And on behalf of Doctor Who fans everywhere, I have to ask – there’s a scene in the film where Richard lifts a small stone from the ground and identifies it as a “krynoid”. Which, as old school Who-lovers will doubtless testify, was the name of the gigantic, killer alien plant in the 1976 Tom Baker story, The Seeds of Doom. Was this a deliberate nod to the trials of one of Matt’s previous incarnations? Daniel is convulsed with laughter.

“That was an in-joke, yes! Just for you.”

And did Matt himself get the joke?

“He did eventually…”

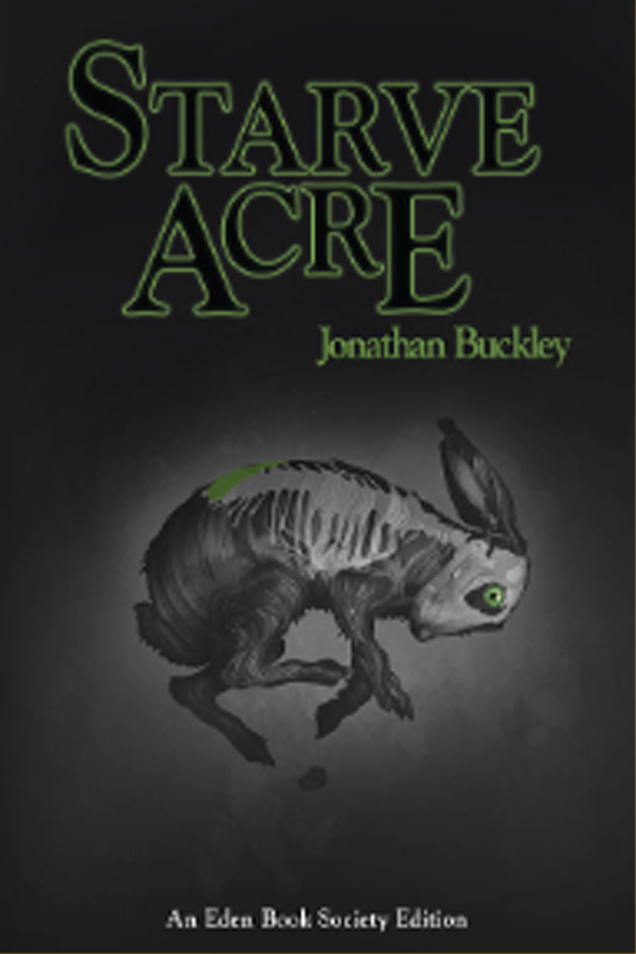

Although neither book nor film explicitly reference the time period in which they are set, both clearly belong to a decade that has become synonymous with a golden age of Folk Horror. Everyone smokes and drives rattly British cars, and the film is a sartorial riot of corduroy and turtle-necked jumpers. That 1970s setting, Andrew explains, derives from an unusual commission that inspired the earliest incarnation of the book. In early 2019, Liverpool-based publisher Dead Ink launched a range of vintage fiction purportedly acquired from the defunct “Eden Book Society”. Among them was a somewhat bloodier version of Starve Acre, this time written – bafflingly – by a forgotten and long-deceased writer called Jonathan Buckley.

“The idea was that Dead Ink commissioned a number of writers to write ‘lost’ horror novellas that had supposedly been unearthed from the 1970s,” smiles Andrew. “So it was good fun – I wrote it under that pseudonym, and I channelled all my love of gory Stephen King horror into it! The story was more or less the same, but it was maybe just a little more violent. And it was a fun exercise – I didn’t have to be Andrew Michael Hurley, I could be someone else.

“Then my publisher at John Murray Press read the Dead Ink version and wanted to republish it as a more literary piece of fiction. So I got rid of the saws and the hammers!”

Without giving too much away, however, there are scenes in the film that seem to derive from this earlier edition of the book, but that aren’t present in the later version. Daniel is smiling knowingly.

“I love both versions of the book, so the film meshes them a bit,” he explains. “I don’t know if you noticed, Andrew – but I shot a scene where one character is going to read a book to Ewan. And he says ‘I’ve got the latest Jonathan Buckley novel’. But it didn’t work, so I had to cut it!”

The 1970s setting, both men agree, also ties the film aesthetically to the decade that produced The Wicker Man, Robin Redbreast, Penda’s Fen and a legion of films and TV productions keen to explore the horrific implications of “what lies beneath”.

“I’m a 1980s and ‘90s child, but the 1970s have always been nostalgic for me because I’m a massive fan of a lot of ‘70s films,” nods Daniel. “Those were the films I watched as a kid, so I was keen to recreate that feel for nostalgic value. But also, it’s an interesting time in terms of male relationships. It comes across in the book a bit – the relationship between Richard and his dad, and the darker side of his dad, was something I was keen to explore in the film. Richard would have grown up in the 1950s, and his dad’s beliefs and strictness would have had an effect on him. For me, that’s the reason Richard comes back to this landscape – he wants to give his son the life he wished he’d had there. And that reflects a lot of father/son relationships around that time. They were difficult.”

For Andrew, the 1970s setting lent the story some practical advantages, too.

“I wanted to set it at a time when those two characters could plausibly be completely isolated,” he explains. “If a weird hare turns up at your house now, there’s probably a dedicated social media chatroom you can log onto! But Richard and Juliette have to deal with the intrusion of this strange creature into their house on their own.”

When it comes to touchstones of 1970s Folk Horror, both Andrew and Daniel are in agreement. The TV play they both reference as a key inspiration for Starve Acre is Murrain, a 1975 drama written by Nigel Kneale for a long-forgotten ITV anthology series, Against the Crowd. Here, a young vet arrives in an isolated rural community where a mysterious illness – the “murrain” of the title – has begun spreading from ailing livestock to local families. In an echo of the folk stories attached to Andrew’s childhood nemesis Meg Shelton, irate farmers are accusing a reclusive elderly woman, Mrs Clemson, of using witchcraft to spread the disease.

“When Daniel and I spoke before the film got going, we talked about Murrain,” says Andrew. “I’ve watched that so many times now and I find something new in it every single time. It’s the ordinariness of it – it could be anywhere. But that ordinariness combines with the menace, and the staunch belief of these people that there’s something supernatural in their midst. I love the way it plays with the clash between scientific progression and the apparent backwardness of magic. And the ending actually leaves you in doubt as to what’s real and what isn’t. It’s just such a great example of that era of Folk Horror.”

Accompanying the film’s release in September is a month-long season of screenings at BFI Southbank in London, curated by Daniel himself. Cinema classics like Don’t Look Now and Eraserhead rub shoulders with similarly eerie small-screen gems: Robin Redbreast and two instalments of the BBC’s classic 1970s A Ghost Story for Christmas series. Baby, arguably the most disturbing episode of Nigel Kneale’s 1976 series Beasts is in there too, and so – rather splendidly – is Murrain.

The modern surge of interest in all things Folk Horror is clearly showing no signs of abating. So why, I wonder as we reach the end of our conversation, have we become so fascinated by the darker side of the bucolic dream?

“It’s something I’ve thought about quite a lot,” admits Andrew. “I think it’s possibly to do with climate change – there’s a sense that we’re losing landscapes and the folklore that goes with them. And maybe Folk Horror is a way of preserving those stories? There’s something real and earthy and tangible about Folk Horror. Wherever it’s set, they’re real places. We live increasingly digital, filtered lives and I wonder whether the mud and the muck of Folk Horror offers a kind of authenticity – these places where stories are buried in the ground.”

“The horror element is also about taking something that we crave and then abusing it in some way,” adds Daniel. “We want to return to a nostalgic time or understand ourselves better by looking backwards, but there are superstitions and darkness there.”

“That’s one of the things that I really like about Folk Horror,” continues Andrew. “It debunks that idea of England being a green and pleasant land and gets to what’s underneath all that. There are so many parts of England where horrific things have happened. The sites of massacres and battles and hangings. You don’t have to look that far back into the past to find them, really.

“And I love the way that Folk Horror gets into that. It’s alluring and seductive to imagine we can go back and live in small communities where everyone knew each other and power was localised. It’s very romantic and idealised, but we can’t go back to that – and when we do, we find a darkness. Something strange and mysterious.”

Starve Acre is in cinemas from 6th September and on BFI Blu-ray and BFI Player from 21st October. Andrew Michael Hurley’s new novel, Barrowbeck, was published on 24th October by John Murray. With thanks to Andrew, David and Jill Reading at BFI.

Why not take out a subscription to the Fortean Times? “The World’s Weirdest News” is available here…

https://subscribe.forteantimes.com/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen