(First published in Electronic Sound magazine #116, August 2024)

THIS CHARMING MAN

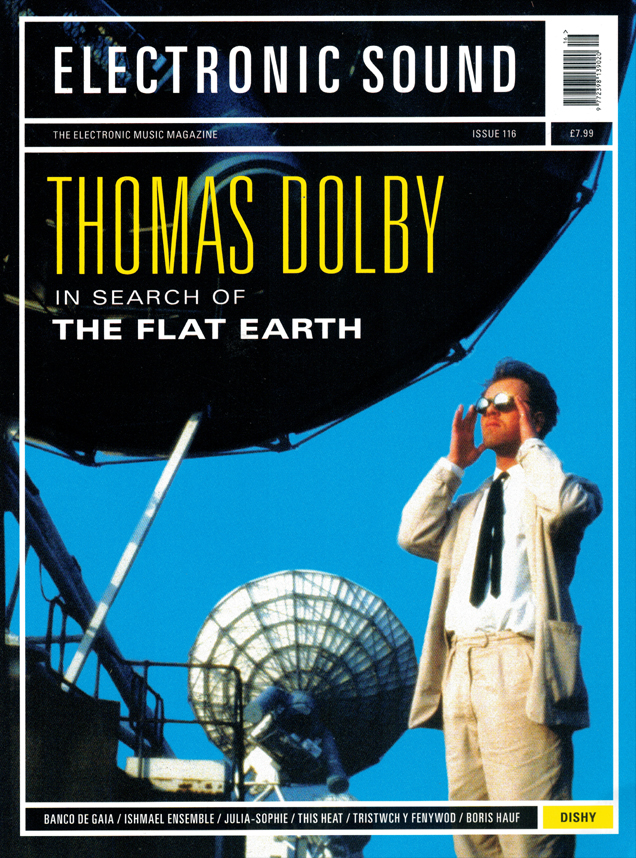

It’s been forty years since Thomas Dolby’s second album, The Flat Earth, saw him outgrow his persona as MTV’s favourite “outgoing boffin” and flourish into a songwriter of impressive versatility. Four decades on, with a new deluxe reissue on the shelves, is he still hyperactive now he’s grown? He may be more reflective, but life – as he explains – still has its fair share of “mystery, urgency and adventure”

Words: Bob Fischer

“I love having a canvas to paint on,” says Thomas Dolby. “With lots of influences from books I’ve read, films I’ve seen, stories I’ve heard, bits of history that I know. I can then hurl them all onto this canvas and make a montage of different lyrical ideas, while also creating sounds to go with them.

“That process of finding good stuff to latch onto, with a strong concept lyrically and sonically – that’s what gets me the most excited.”

It’s an approach that, forty years ago, led him to a career highspot. Dolby’s second album, The Flat Earth, was released in February 1984 and that metaphorical canvas couldn’t have been more enthusiastically splattered. Keen to expand his horizons following the success of 1982 debut album The Golden Age Of Wireless, Dolby threw Soviet dissidents, Malaysian rain forests, technology-fuelled ADHD and some deceptively personal confessions into an album whose combination of organic, jazz-tinged fluidity and chart-friendly funk swiftly transcended his public persona as a wacky, synth-pop eccentric.

Four decades on, Dolby looks back on the album with beaming affection. He’s based on the US East Coast these days, and the lifestyle clearly suits him. He looks fabulous. He is parked up in a Tesla charging bay, and is slim, tanned and boyish, replete with a brand new head of luxuriant silver hair: a recent addition whose arrival he has unabashedly detailed on his own Youtube channel. He smiles sheepishly when I compliment his vintage Television t-shirt. And, indeed, his new barnet. Now 65, he looks 15 years younger, exuding the laissez-faire charm of a man deeply at ease with himself.

So, let’s dive right in. The Flat Earth. What are his memories? Was there – as every hoary old hack has put it since the Neolithic era – a hint of “difficult second album syndrome”? A whiff of success, and suddenly the pressure was on?

He looks modestly unconvinced.

“Well, The Golden Age Of Wireless had come out and got a few good reviews in NME and Sounds,” he recalls. “But it had got very limited radio play in the UK. EMI were just saying ‘Look, this a good start and we’re committed to you, so let’s keep going’.

“But the next thing that happened was that it became apparent to me that music videos were a new platform. It wasn’t just about radio and touring any more, it was suddenly possible to have commercial success off the back of a popular music video. I had connections with Bruce Woolley of The Buggles, and they’d had a No 1 single around the world without much touring presence or radio play. So I saw music videos as a whole other form of expression. It wasn’t just a way of promoting yourself, it was an opportunity to make a little movie in four minutes.

“And I saw them as silent movies, with a soundtrack composed by me. The silent movie stars were clever, unheroic characters, people like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. They’d escape from the bullies’ clutches and win the girl! And that was the way I viewed myself, as the ingénue male character. So I went to EMI and said I really wanted to make videos. I showed them a storyboard for ‘She Blinded Me With Science’, with little drawings that I’d done. They said ‘We like the idea, but where’s the song?’

“I said ‘Ah… I’ll bring that in on Monday!’”

Retreating to his studio (“on a Victorian trading estate in Earl’s Court,” he smiles), Dolby crafted this irresistible between-albums breakthrough single over the course of a single weekend. And the accompanying video was true to his vision. Complete with traditional silent movie caption cards, it depicts the white-suited Dolby’s arrival at the sprawling, grandiose “Rest Home For Deranged Scientists”, a facility administered by loose-limbed TV boffin Magnus Pyke. It is, as he says, a terrific little movie in four minutes. MTV was smitten, and Dolby – who, barely four years earlier, had been catching the bus from Putney to work in a ramshackle fruit and veg shop – found himself with a US Billboard Top 5 hit on his hands.

“All of this was going on while I was rehearsing in a cottage in Oxfordshire with my band, getting ready to go into the studio and record The Flat Earth,” he smiles. “Then we went to Brussels to record with a guy called Dan Lacksman, a legendary electronic producer over there. So we were in Belgium when the American record company said ‘Can you put that on hold while you come over here and promote your single? Because it’s taking off’.

“So that’s a roundabout way of saying the experience of making the second album was more me thinking ‘I can have a free hand creatively so long as I keep playing the record company game of having a single that we can promote on the radio’. I felt that was my ticket to being at liberty to make whatever music I wanted. So if anything with The Flat Earth, I went more leftfield. Because in my back pocket I had ‘Hyperactive’, which was the single from the album that could keep EMI happy and keep up the momentum we were building with ‘She Blinded Me With Science’. So I don’t think it’s a typical second album story!”

You can make a strong case for Thomas Dolby being the perfect interviewee. His recall is immaculate, his answers come in perfectly-formed paragraphs. He has spent the last decade working in academia, as Homewood Professor of the Arts at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, and you can almost hear him mentally inserting parenthesis and citations into a string of thoughtfully erudite answers. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone whose conversation is so devoid of “umms” and “ahhhs”.

This meticulously curious mind gleefully decorated the canvas of The Golden Age Of Wireless with – by his own admission – songs about “things”. Things like the Cold War, totalitarian repression and nightmarish dystopias, all set to deceptively danceable beats. Was The Flat Earth a little more personal, though, I wonder? It’s an album that occasionally feels like there’s more of the inner Thomas Dolby in there.

“It’s definitely more introspective,” he nods. “‘Screen Kiss’ and ‘Mulu The Rain Forest’ and the title track – they’re more personal. I think what you saw emerging on The Flat Earth was a willingness to not use my persona as a barrier. To put away the ‘outgoing boffin’ brand and actually let my guard down and be vulnerable enough to go into my internal feelings a bit more.”

Even the album’s opening track, a quintessentially 1984 homage to the appalling fates then befalling Cold War-era Soviet refuseniks, had a subtly confessional aspect.

“‘Dissidents’ was probably more about my personal relationship to writing,” he explains. “As I mentioned, I had a delicate balance of playing the record company game, feeling that was the ticket to artistic freedom. But sometimes that felt at risk. Occasionally, you’d get hints of ‘We could pull the plug on this any time. We don’t have to keep promoting you, there are other artists we could be pushing – we could just drop you’. And I think ‘Dissidents’ was more me externalising that and projecting it onto Russian writers and activists, and politicians being sent to Siberia.

“That idea was very evocative to me, the Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn types who were expressing themselves and making their art at the possible risk of their own liberty. That was very powerful to me, and very inspiring.”

Meanwhile, I suggest, ‘Screen Kiss’ feels raw. “There’s a movie I wouldn’t pay to see again / If it’s the one with him in,” sings a plaintive Dolby, comforted by breathy synths and a mournful, fretless bass. His excellent 2017 autobiography, The Speed Of Sound, pins the inspiration on an unsuccessful relationship forged in the maelstrom of that first American promo tour. When he hears these songs four decades on, how do they feel? Are they almost private diary entries sent forth into the world?

“Yeah,” he says. “I think everybody has those milestones in their life – personal, work, family. And that was a definite milestone. Although one of the many ways I’ve been lucky has been in relationships – I had a few stormy affairs like that, but then I met the love of my life forty years ago. I was incredibly fortunate in that. So although relationship and break-up songs are a source of much inspiration, I don’t have very much to draw on in that area.”

Which is good, I guess? No-one should need to be truly tortured for their art. He nods.

“I did a song called ‘Cruel’, which is a regretful relationship song,” he recalls. “And Larry Treadwell, my guitarist at the time, listened to it. At the end he was very quiet, and he said ‘I want to call every girlfriend I ever had and tell them how sorry I am’.”

Even ‘Hyperactive’ came from the heart, a personal expression of his manic but perhaps overwhelming delight in the attention his new-found fame afforded him. Is there almost a case of ‘Help!’ syndrome going on here? To the world at large, it was a jolly Beatles song from an endearingly wacky film. For John Lennon, it was the first truly autobiographical song he had ever written.

“I guess he felt he got trapped by stardom?” asks Dolby. “I never felt that, but I found it very curious. It was like being in a fishbowl. I’d be behind my specs and the flashbulbs would be popping, and when I walked into a room people would part like the Red Sea. And this was pop stardom on a fairly minor scale! I found it very curious and very odd, and a little bit uncomfortable.

“It became most uncomfortable when I thought ‘Two years ago, I was a wallflower and nobody noticed me at all – now they’re noticing me, but they’re still not treating me like a regular human being!’ But you can’t let those kinds of thoughts take over. You’ve got a job to do like anybody else, and there are aspects of the job that are not entirely comfortable, but you take a deep breath and you go out and do that job. As John Lennon did for a good number of years.”

That “outgoing boffin” brand arguably came to define him in the earliest years of his career. To the press at large, he was the eccentric mad synth scientist, screaming ‘Eureka!’ at the successful conclusion of every bubbling Fairlight experiment. The Flat Earth, however, tells a different story. The story, perhaps, of a shy music fan rediscovering a love of music arguably painted in gentler, more whimsical shades.

It is, I suggest, a very organic album. ‘I Scare Myself’ is a cover of a song by Dan Hicks, purveyor of humorous jazz-tinged country music. And ‘White City’ features a delightful monologue from Robyn Hitchcock, indomitable keeper of the British psych flame. He plays a character called Keith and moans about the dreariness of the A45 in Bedfordshire.

Dolby laughs affectionately at the memories.

“Robyn Hitchcock soundchecks are great!” He beams. “The engineer will say ‘Robyn, can you try your mic?’ And half an hour later he’s still going. So the bit of Robyn that’s on ‘White City’ is just a little slice of one of his soundchecks. But yes, it’s an organic album. I think people in the media look for a way to pigeonhole you and they’ll take whatever you put in front of them. Clever people – or people more clever than me – know that if you get photographed in front of a synthesizer, they’re going to call you a synth artist. Period. And if I’d chosen instead to be only photographed out in the woods or in a more spiritual setting, then that would equally have informed the way that people described me.

“It’s like how David Bowie was never really photographed in front of a saxophone. We knew from the few bits he recorded that he was a pretty good musician, and he was photographed with a guitar once or twice, but never with a sax. I remember asking him about that before Live Aid. I said ‘Why don’t you play a bit of sax?’ He said ‘No, that’s not the way people view me. It’s for my band to be viewed as musicians, I’m the frontman’.”

For a man who modestly confesses his pop stardom came on that “minor scale”, Dolby has kept some extraordinarily illustrious company. Putting the finishing touches to the video for ‘She Blinded Me With Science’ in a London editing suite, he encountered – on a secret 1982 visit to the capital – Michael Jackson, overseeing the final cut of his video for ‘Billie Jean’. The unlikely duo swapped both compliments and phone numbers. Months later, on a promotional visit to help push his single even higher up the Billboard charts, Dolby found himself at a loose end in LA. The only local number he had in his Filofax? Yep. A call was made, and the gates of Jackson’s mansion swung open.

If we’re talking public personas, there are few more complex than the convoluted perceptions of one Michael Joseph Jackson. But what was the future King of Pop like as a person? We all know the image, but how was he as a man, sitting down to chat amiably over afternoon tea and biscuits?

“Surprisingly approachable, actually,” says Dolby. “We related. We had more or less the same birthday in the same year, we’d both travelled a lot as kids, and he was very into the tech side. He’d just bought a Synclavier and he wanted to know if was better than a Fairlight, and he had questions about my production techniques. So it was all very normal, very down to earth.

“He was a very gentle guy, not at all egotistical. And his household was bizarre, but it didn’t strike me as creepy. He was an overgrown kid himself. He had a bunch of local kids there in pyjamas playing with Tonka toys, but there was nothing about it that gave me the shivers. And I loved his music. I remember when ‘Billie Jean’ came out, it felt astronomical. That and ‘When Doves Cry’ were the musical highlights of the 1980s.”

And did Dolby and Prince ever cross musical paths?

“I never got to work with him,” he says. “He tended to prefer blonde goddesses! But I met him on a couple of occasions. And I did a show in Minneapolis, at the club where they shot ‘Purple Rain’, and I heard he was coming. There was a balcony that had been blocked up, and about two songs into the show, the curtains parted and he took his seat on a sort of throne. Then, a song later, the curtains closed and he left! I was flattered that he checked me out, but slightly sad that he didn’t see fit to stay for longer.”

That aforementioned autobiography, The Speed Of Sound, is filled with such eyebrow-raising encounters. Dolby comes over at times like a musical Zelig, popping up at pivotal moments in pop history with remarkable regularity. He was, as he has already alluded, Bowie’s keyboard player at Live Aid. At the 1985 Grammy Awards he took part in an onstage ‘Synthesizer Showdown’ alongside Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock and Howard Jones. That same summer, he was persuaded by George Clinton to sing ‘Sex Machine’ at a James Brown tribute evening, with Brown himself grinning mercilessly from the front row. Yegods, even before he found fame, he made a cameo appearance as Barbara Gaskin’s elusive “Johnny” in the video for 1981 chart-topper ‘It’s My Party’.

There’s a question, I apologetically tell him, that I can never resist asking anyone who shot to pop fame in the 1980s. What was his Traffic Light Sandwich moment? The bizarre promotional spot, the kid’s TV show, the moment when – splattered by gunge and cheered on by a party of cub scouts – he finally thought ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ I only ask because I once interviewed Andy McCluskey from OMD, and he gave me the immortal quote: “I started a band because I wanted to be in Kraftwerk, and I ended up making Traffic Light Sandwiches on children’s television with Timmy Mallett.”

Dolby is shaking with laughter.

“I think that would probably have to be when the Muppets asked me to explain synthesisers to them!” he grins. “The Jim Henson gang had a series called The Ghost Of Faffner Hall – these were muppets that were ghosts, but the show also had an educational remit, like Sesame Street. They said ‘We’d like you to have a crack at explaining synths’. So I talked about oscillators, and opening and closing filters so the buzz changes pitch, and they said ‘Oh, you mean like a little fly?’. They then had the idea of putting a fly puppet inside a matchbox, with me saying ‘The harder I shake the box, the higher the fly buzzes – like an oscillator!’ And when I opened and closed it, the fly was saying ‘Let me out!’

“But that was a fun thing – it wasn’t the same as making sandwiches. And I did stay in touch with the fly puppeteer actually, he’s still around! He’s one of the characters in Star Wars, but I can’t remember which one…”

Star Wars? I ask, gleefully. Go on then, here’s another one for your local pub quiz. Thomas Dolby’s abandoned 1980s car is, to this day, used to create sound effects for Star Wars and Indiana Jones films. True or false?

“Absolutely true!” he laughs. “In the middle of the 1980s, I worked on an ill-fated movie called Howard The Duck, at Lucasfilm in Northern California. I was there for a few months because I was writing the songs for it, and training an all-girl band to be musicians for the film. It ended up being a bit overblown and out of control, so it’s not something I’m too proud of – although the songs are good.

“But while I was living there for three or four months, I needed transport and I found an old Morris Minor convertible covered in surf stickers. My plan was to export it back to the UK, but I never got round to it. I left it there, came back myself and got busy. About three months later, I got an answerphone message from the transportation manager at Lucasfilm, and I thought ‘Oh no, he’s going to be bugging me about getting rid of my car’ – because I’d just left it in the parking lot at Lucasfilm.

“So I ignored it. But years later I was talking to Gary Rydstrom, a famous Lucasfilm sound designer, and he said ‘Oh yeah, we still use your car all the time for foley. In the corner of a studio in San Rafael we have your Morris Minor, and we smash it to pieces every time we need a good metallic sound!’ So there’s not much left of it, but it’s still there.”

There’s a telling moment in his book, I tell him. Contemplating the possibility of cosy domesticity with a longstanding close friend, he decides not to pursue the romance, claiming the lure of “mystery, urgency and adventure” is simply too strong. And we’ve barely scratched the surface of those adventures here. As his fame was burgeoning, he became an in-demand keyboard player, gracing career-defining albums by Def Leppard and Foreigner. As an established solo artist in the early 1990s, he persuaded childhood heroes Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir of The Grateful Dead to play on his Astronauts And Heretics album. As producer, he is surely the only man in the world to have worked with both Joni Mitchell and Prefab Sprout.

As adventures go, these are pretty damn impressive. Is it still a pull he feels, I wonder? Does he still have the wanderlust, the passion to pack his life with these delightfully offbeat capers?

“Yeah,” he nods. “But to a lesser extent, I think. I’ve been teaching now for ten years, and part of the motive behind that is that I almost feel I’d like to pass on the knowledge that I’ve gained from all those adventures. When I think of 18-year-old kids with talent today, it’s unlikely they’d go down the same path as me. In the same way that there aren’t really Nile explorers any more!

“The world has shrunk. There are fewer unknown places that are uncharted, and the same is true of the kind of adventures we’ve been talking about. Collaboration is so much easier now with the internet, you don’t have to travel and get into a room with someone and interact face-to-face. That piece of the adventure has been taken out of the equation, you now have this insulating layer of e-mail and social media.”

“Because of my personality, if I found myself in a control room with Mutt Lange and Def Leppard, it was a really odd experience. On paper, I’ve got zero in common with those guys – Def Leppard grew up in Sheffield in a heavy metal band, Mutt was from South Africa and had to go into the woods listen to black bands because he would have been arrested if he’d tried to do that in the city. So they had great stories to tell, but it was awkward. Getting into a studio with Eddie Van Halen? Awkward. Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir from The Grateful Dead? Well, I’m not a natural party animal.”

So does he feel his shyness held him back from even greater adventures? Or has it been an integral part of the chemistry he has forged with – ahem – these slightly more outré figures from the wider rock pantheon?

“Interesting stuff happened because of that chemistry,” he explains. “What I found very often with these people was that they wouldn’t see me unless they liked my stuff, and then, when they got in a room with me, they’d try to sound like me. I’d been a Dead-head when I was 14 or 15, I saw them at Alexandra Palace. I wrote a song called ‘Beauty And The Dream’, and I’d always imagined Garcia and Weir playing on the end of it, with these soaring guitar lines. But when I got in the studio with them, Garcia was trying to play like ‘She Blinded Me With Science’!

“So those are really the adventures that I was talking about. And when you have to fly off somewhere to do those things, other things crop up along the way. It’s not just studios and hotels and backstage, it’s also the people you meet and the invitations you get. The interactions with fans… 99% of them just want a selfie or an autograph, but 1% will say ‘I’m having a barbecue at the weekend by lake in Michigan, with a bunch of friends who all work for a pharmaceutical company. What are you doing?’ And I say ‘Nothing – I’m going to come!’ So I liked that travelogue aspect of the job, using the opportunities my career afforded me as a springboard to having a real life. Which otherwise, I don’t think I would have had.”

There are five Thomas Dolby albums. Four of them were released during the first ten years of his recording career: The Golden Age Of Wireless (1982), The Flat Earth (1984), Aliens Ate My Buick (1988) and Astronauts And Heretics (1992). The fifth, A Map of The Floating City appeared after a near two-decade gap in 2011. There have been no shortage of adventures since, not least in the world of tech: he was the co-founder of Headspace Inc, a company creating polyphonic ringtones for millions of mobile phones. He has directed an acclaimed film documentary about the demise of the Orfordness lighthouse that once illuminated his Suffolk garden. And now there’s a new novel, Prevailing Wind, a tale of historical skulduggery among the New York sailing fraternity of the early 20th century.

But no more music.

Does he miss it? His passion for live performance seems undiminished, but will there ever actually be a new Thomas Dolby album?

“That’s a complicated question,” he frowns. “Put it this way – I haven’t got a stockpile of unrecorded songs. And I think part of that is down to the fact that, when I write songs, I sort of reverse engineer them from the moment when the public gets to hear them for the first time. In the old days, that would have been Radio 1 saying ‘Here’s the new one from Thomas Dolby!’ And knowing that people all over the country were experiencing it right then.

“Or it might be me visualising a stage with a spotlight and a grand piano, and a guy walks on, sits down, adjusts the piano seat and starts to play. What does that sound like? What would wow me, what would be wonderful? A lot of my inspiration comes from taking that moment of discovery from the audience and figuring out what I need to create to fill that hole.

“But at this point in time, for me to put out an album? Well, there isn’t some huge record company that’s going to give me a big contract, get behind it and have a team of people out there. It’s going to be more a case of me picking various self-publishing options. Or do I try to find a big-shot manager that’s also going to take a big commission? When I think of that whole path, it doesn’t excite me. I could make something in my backroom and put it out there, and it would get a little bit of attention – I’ve got my hardcore fanbase and they would love it – but then it would vanish without trace.”

He’s philosophical, but his wariness of the mechanics of the music industry clearly cuts deep. The sales for A Map Of The Floating City in particular disappointed him.

“I came with up with lots of ideas related to the internet and social media, and I created a multi-user online game where you earned downloads,” he recalls. “And I toured with the time capsule, this little teardrop trailer behind the tour bus that you could go into and film a message for the future. I got really creative with the marketing, but it still more or less sank without trace. Of the expectations I’ve had for all of my albums, that was one of the most disappointing.

“Because I think it’s probably the best work I’ve ever done. It may not be people’s favourite, but on a personal level I think it was a tremendous achievement. And I always want to go one better – I’m never going to settle back and think ‘Book some studio time, get with some friends, make some songs, and when you’ve got enough just call it an album’. I’m not going to settle for that, it always has to be something above and beyond.

“So because I don’t hear a strong sucking sound, it discourages me from sitting down to write something to fill that vacuum.”

The slight sucking sound, though? The possibility of turning Prevailing Wind into a full-cast audiobook, complete with a potential new Thomas Dolby soundtrack.

“An upswing in the book industry is the idea of dramatising audiobooks,” he explains. “A little like the radio plays we grew up with on the BBC, but they’re not all lovey and narrated – they’re cast with good actors, and they have great sound design and scores. There was one for 1984 recently, with music by Matt Bellamy from Muse. It’s an upcoming trend, and I did put a scene from Prevailing Wind on my Youtube channel. I read it with a couple of actors, used some existing instrumental music, and I had a great time doing it. So I’m now thinking about doing the whole book that way.

“And you know what it reminds me of? The early days of MTV. And that really appeals to me – as you know, I love being on the cusp of something that’s still unexplored. Something that hasn’t yet been defined. I find that very exciting, and it really does inspire me. But making an album, single, touring? Not so much.”

It’s been an hour, and we’re almost at the end of our conversation. He’s been funny, charming, thoughtful, illuminating, and I’m sorry to say goodbye. The Tesla is fully charged and he has another appointment to reach, but he’s happy to chat while he drives, so – as the Baltimore landscape whizzes past the window – I ask him, four decades on, to look back one final time at The Flat Earth. There’s a new, expanded 40th anniversary edition freshly on the shelves. Is it an album he thinks of fondly? Has he even listened to it recently?

“I listen to it a lot, and I’m very proud of it!” he smiles. “I think it’s sonically brilliant. It ranges from the high-end production values of ‘Dissidents’ and ‘Hyperactive’ to the intimacy of ‘Spring Kiss’. A lot of great things came together with the personnel, too. It really worked. And if somebody comes bounding up to me after a show and says ‘Oh man, I gotta tell you…’, then the next thing out of their mouths is going to be The Golden Age Of Wireless, The Flat Earth, Aliens Ate My Buick or Astronauts and Heretics. It’s roughly equally distributed between those four albums, but it’s probably a little bit more for The Flat Earth.

“And if that’s what I’m remembered for, that’s great.”

The Flat Earth (40th Anniversary Edition) is out now.

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen