(First published in Issue 110 of Electronic Sound magazine, February 2024)

TALES FROM THE LOOP

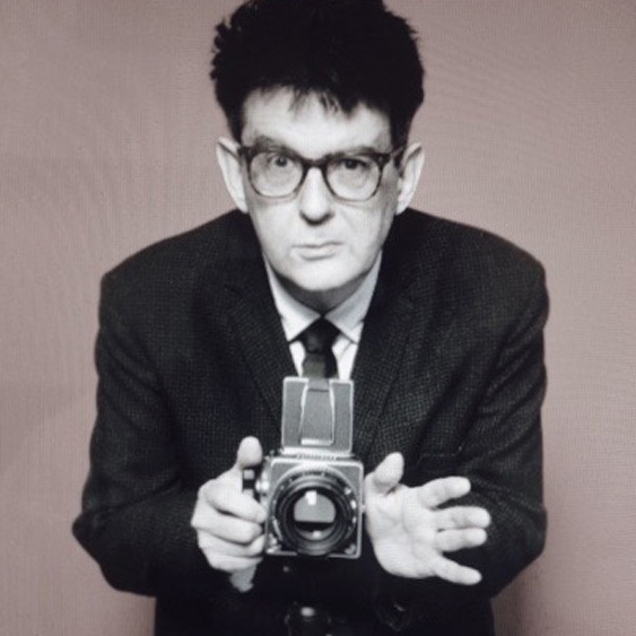

Sound obsessive, tape looper extraordinaire, godfather of hauntology, and – most unlikely of all – teen pin-up. For five decades, Drew Mulholland has been walking a very individual path

Words: Bob Fischer

“I once had a dream that I was in a club, in a box overlooking the stage,” begins Drew Mulholland. “Glen Matlock, Paul Cook and Steve Jones came out and started playing the most amazing Sex Pistols riff ever. But then the singer appeared, and it was Sid James. Dressed as he was in Carry On Camping. And the group was called The Sid Pistols! While the riff was playing, he just walked up and down the front of the stage, leering and laughing at the girls in the front row. ‘Hyak, hyak hyak…’

“Some time later, I was playing my Anarchy In The UK single at home. I put it on and walked away from it, but I’d forgotten to change the record player from 33rpm to 45rpm. So when Johnny Rotten started laughing – ‘Hyak, hyak, hyak’ – it sounded exactly like Sid James! I thought ‘Have I always known that? Did my brain recognise that and put it into my dream?’ It’s a weird connection…”

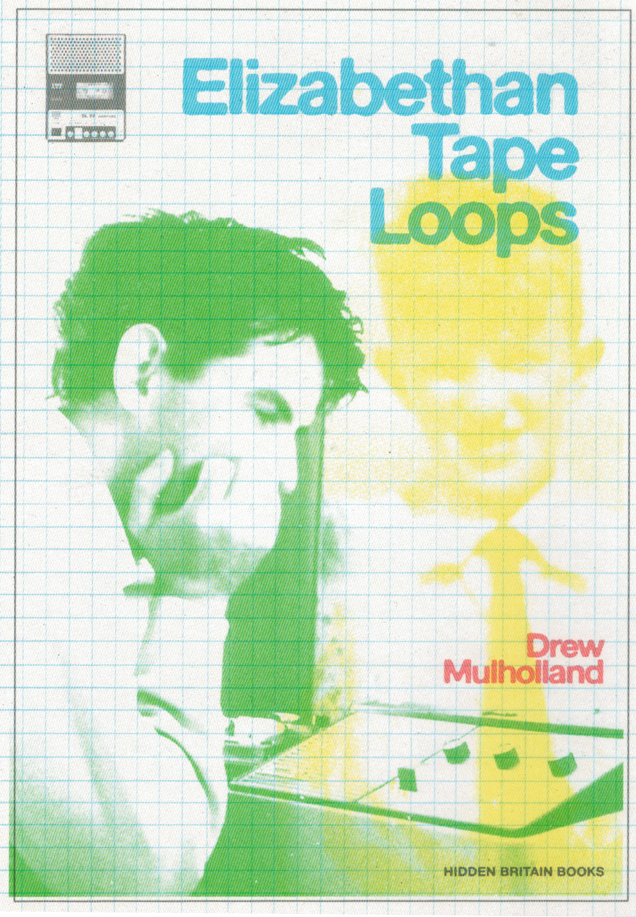

It’s a dark and filthy winter’s afternoon, and freezing rain is lashing against the windows of Drew’s book-lined Glasgow apartment. But we have steaming coffee, apple turnovers and are cosily contemplating the interconnectedness of all things, so life is sweet. Drew Mulholland is splendid company, and he’s now spent over fifty years exploring those “weird connections” – between sound, music, memory, the paranormal and pretty much everything else in between. His new book, Elizabethan Tape Loops, is a love letter to what he calls “the path”… and the teenage friend who began the journey with him, back in the early 1970s.

“I was walking down the road one day when I saw Paul Canavan in his garden,” remembers Drew. “I was absolutely convinced I knew him from somewhere, so I stopped and said hello and we just started talking. And we never stopped.

“Paul was a couple of years older than me, and had friends at school a couple of years older than him. He came in one day and said ‘You know Marek? He’s got a group called Lodestone and they’ve made a tape.’ He put it on, and it was the sound of a ball bearing rolling down a drainpipe… and it just kept going. I said ‘What’s on the other side?’ And Paul said ‘No, look!’ And, inside the cassette, was a home-made tape loop. And it was just… [he visibly shivers] I can feel it even now. ‘This is brilliant – and anyone can do it. Which means I can do it’. Up until that point, people who made records lived in mansions. But this was an ‘in’ for people like us. We instantly started making tape loops ourselves.”

It was 1973. Drew and Paul lived in Mount Vernon, a “weird little island” of an east Glasgow suburb, their houses sandwiched between a railway breaker’s yard and a farmer’s field riddled with spent wartime ack-ack shells. And their interests in the more esoteric aspects of the musical world expanded even further when Drew discovered the illicit thrills of shoplifting. In particular, the Radiophonic Workshop’s 1976 album Out Of This World. Where did he pilfer it from, I wonder? The Glasgow Woolworths?

“No, it was more dangerous than that,” he smiles. “Do you know the Barras Market? It’s in the east end of Glasgow, and if a stallholder caught you shoplifting… well, he wouldn’t call the police. I’m not going to say any more. But I was fifteen, I had no money, and I thought ‘Right, I’m having this’. It looked spacey, and it had Doctor Who on the sleeve. And the tracks that jumped out at me were all credited to ‘DD’ – Delia Derbyshire. Sound effects albums were a huge thing for me, too… motor boats panning from left to right! They were brilliant.”

I was the same, I tell him. The idea of using sound as a medium to transport me from the everyday humdrum was incredibly alluring.

“That was it,” says Drew. “It was the sound world that interested me, then the electronic music. All these things coming from different directions that seemed to make a whole.

“Then Paul and I got very interested in the Baader-Meinhof group, and why it was happening. Paul said ‘Could you make me the sound of a terrorist attack?’ So I got my BBC Sound Effects albums and made a recording, but I let the blank tape run for about forty seconds first. So when Paul came round, I said ‘I’ll get some tea’ and went into the kitchen. And my timing, for once, was spot on. I gave him his tea then went back for biscuits, counting down ‘7-6-5…’ in my head. Then it went off, and it was very loud. I heard a yelp, and Paul had spilt PG Tips all over his crotch.”

Punk happened. There was a photocopied fanzine called Mount Vernon’s Burning and a short-lived band, The Targets (“I was thrown out of my own band in my own garage,” sighs Drew). But unlikely dreams of pop subversion were beginning to coalesce.

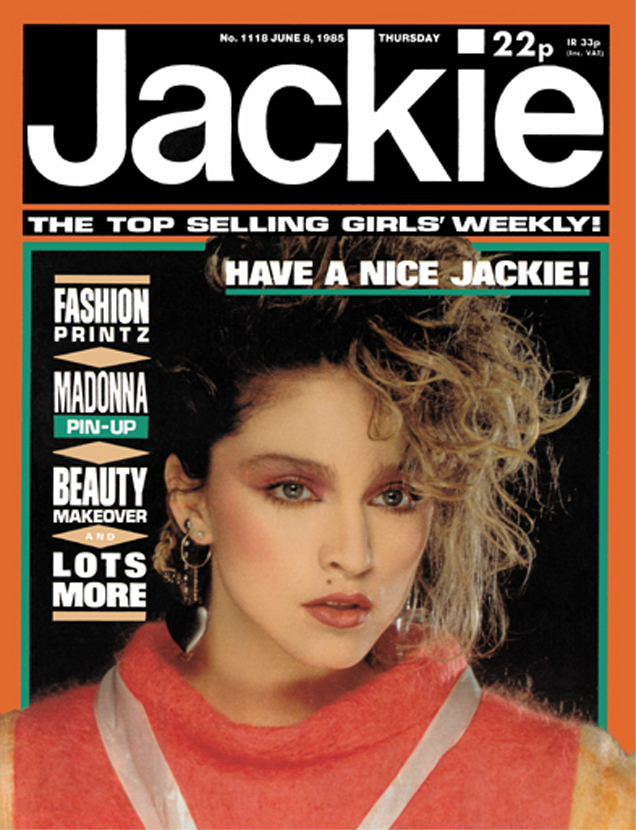

“Paul introduced me to a guy called Dennis, who had a bass and needed a guitarist,” says Drew. “We met up and got on like a house on fire, we got a singer and a drummer, and we called ourselves Pioneers West. We had the ridiculous idea of writing the most poppy 1980s music imaginable to get signed by a big label, then telling them we weren’t doing that stuff any more and recording all this weird stuff instead. We had a friend, Alex, who became our manager, and he phoned up one day and said ‘I’ve got you a piece in a magazine. It’s a double page spread in Jackie…”

What??! You were actually in Jackie, the magazine for teenage girls?

“Yep,” he confirms, visibly wincing. “June 1985, Madonna was on the cover. The angle was that we didn’t yet have an image, so Jackie said they would come up and do pictures of us, before and after. They sent us shopping with two really nice young women, then to a photographic studio in the west end of Glasgow with these rotten Duran Duran clothes on. It was just horrendous. And I’ll never forget: when we were getting changed afterwards, our keyboard player put his arm around me and said ‘Drew, think about it. When we get signed, every day will be like this’. I just said ‘I’m leaving. This is absolutely shite, and there’s nothing about it that interests me’.”

He remains publicity-shy, with a sense of modesty that is – he suggests – almost part of the genetic make-up of east Glasgow. A recently-released compilation, Deltic Vespers, showcases his four-track recordings of the 1980s and they’re a mile away from the pop dreams of Jackie magazine. Scary tape loops and drones are interspersed with ‘96 Tears’-style garage workouts. By 1996 he was recording as Mount Vernon Arts Lab, with cassettes initially sold through local record shops (“They were in see-through bags from Tesco”) attracting a burgeoning fanbase. Teenage Fanclub’s Norman Blake and Pete ‘Sonic Boom’ Kember featured on 1998 debut album proper Gummy Twinkle, and Kember – Drew reveals gleefully – even put him in touch with Delia Derbyshire for a series of life-enriching phone conversations.

“He found her in the Northampton phone book,” he smiles. “After we got to know each other, Delia would tell me stuff about meeting Brian Jones and The Beatles. It was all new-fangled pop music to her, but she had enough about her to connect with people like that. It was a very enjoyable education – I was talking to someone who was there for all the stuff I’d grown up reading about.”

Warminster, meanwhile, was a 1999 collaboration with Portishead guitarist Adrian Utley. A Radiophonic-inspired exploration of a spate of 1970s Wiltshire UFO sightings, it showcased Drew’s lifelong fascination with the otherworldly.

“I only remember one big argument with my dad,” he recalls. “He said you could time travel to the past, but you couldn’t go into the future – and I disagreed with him! We watched a lot of sci-fi and horror films, and if something came up in the film we’d run with it and have discussion after discussion. The books I had as a kid were all about the Bermuda Triangle and Charles Berlitz and my dad was the same as me – we were interested in why people believed in it all.”

The fascination peaked on The Séance at Hobs Lane, a 2001 album exploring 18th century occultism, Quatermass And The Pit, and the psychogeographical resonance of abandoned underground stations. Blake and Utley contributed again, together with Coil’s John Balance, Add N To X’s Barry 7 and Belle & Sebastian’s Isobel Campbell. It’s a stunning piece of work, and – with hindsight – a distinct turning point on “the path”. But it was only five years later, during a lean musical patch, that the album really began to gather its own momentum.

“My daughter was in a newsagents looking for a comic, and I picked up The Wire magazine,” explains Drew. “I hadn’t seen it for years but I opened it at random, and there was Mount Vernon Arts Lab! They were interviewing Jim Jupp from Ghost Box Records, who said one of the main influences in founding the label had been The Séance at Hobs Lane. I e-mailed him and said ‘Thanks – it’s nice to know that album has a life of its own’. Because as far as I was concerned it was all over. But he mailed back and said ‘Can we re-release it?’.

“That was the beginning of Part Two, really. The next phase.”

And so, accidentally, Drew Mulholland became Godfather of Hauntology. For the last decade, his interests have taken him from sweat-soaked gig venues to academic halls. He has worked in the psychology department of Glasgow Caledonian University, and been the geography department’s official composer-in-residence. There have been an overwhelming flurry of new albums – including Three Antennas In A Quarry, a realisation of a lost 1960s score sent to Drew and Pete Kember by their beloved Delia Derbyshire. His love of the uncanny remains paramount, together with his adoration of vintage horror films, an obsession reaching its apex on 2019’s The Wicker Tapes.

“I went with a friend, David, to do the Wicker Man tour,” explains Drew. “We visited all the film locations, and nothing had changed. We got to the pub door, two grown men, and I said ‘I can’t go in!’. But the last place we went to was Burrow Head, and David called me over excitedly. There they were… the stumps of the Wicker Man’s legs. With broken wood from them just lying around on the clifftop. I said ‘Back to the car, get as many carrier bags as you can!’”

There is, I suggest, an alchemical quality to his tape experiments. Loops created for The Wicker Tapes were spooled around one of the Burrow Head slivers, a fragment of the actual Wicker Man itself. For 2020’s A Haunting Strip Of Marshland, he ground lichen with a pestle and mortar and glued it to the master tapes. Does his interest in the paranormal, I wonder, stretch to the recording process? Can these physical rituals somehow magically imbue his albums with an extra essence of the inspiration behind them?

“It depends,” he says. “You’ve got a tape loop going round a piece of wood from ‘The Wicker Man’. So on one level, it makes a physical impression on the tape. But then we head into fantastical thinking. Is there something about The Wicker Man in this piece of wood that somehow goes into the sounds on the tape? And that’s a psychological area. There’s a classic psychology device… the lecturer comes out carrying a cardigan. He gives it to the students and asks what they think of it as they pass it around. And they say ‘Nice design, bit retro’. ‘Oh, you like it then’? ‘Yeah!’. And then he says ‘It used to belong to Adolf Hitler’.

“So instantly, it becomes something else. And obviously, it’s just the lecturer’s cardigan, it never belonged to Hitler at all. But it’s the same principle as the wood from The Wicker Man. ‘Here’s a piece of wood…’ ‘Right’. ‘Here’s a piece of wood from The Wicker Man. ‘What?!!’. And that’s the area I’ve gone into, without realising it.”

But those properties are something we impose, rather than something intrinsic about the object itself?

“Yes, they come from us.”

He talks excitedly of future projects. 2024 will see an album based on the portmanteau horror films of the 1970s and a collaboration with Generation X guitarist Derwood Andrews that also features the fretboard talents of Paul McGann – yes, that Paul McGann. “The path,” as he describes it, has been long, winding and fascinating. And the book, I tell him, feels like a tribute to the man who was there at the start. Drew’s teenage comrade Paul Canavan died in 1997, and Elizabethan Tape Loops is clearly an extended thankyou to his friend.

“Yeah, it is,” smiles Drew. “I thought I had to acknowledge that where I’ve ended up is all down to that man. And of course, in writing it, I’ve remembered things, places, smells. Phone calls on Saturday mornings: ‘Get down to this house, you’ve got to hear this record! What do you mean you’ve never heard of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band?’”

So Paul started it all?

“Yeah…”

He pauses, and the Glaswegian modesty gene kicks in once again.

“Or it’s his fault.”

The Séance at Hobs Lane has just been reissued for a second time by Ghost Box Records:

https://ghostbox.greedbag.com/buy/sance-at-hobs-lane-0/

Electronic Sound – “the house magazine for plugged in people everywhere” – is published monthly, and available here:

https://electronicsound.co.uk/

Support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen