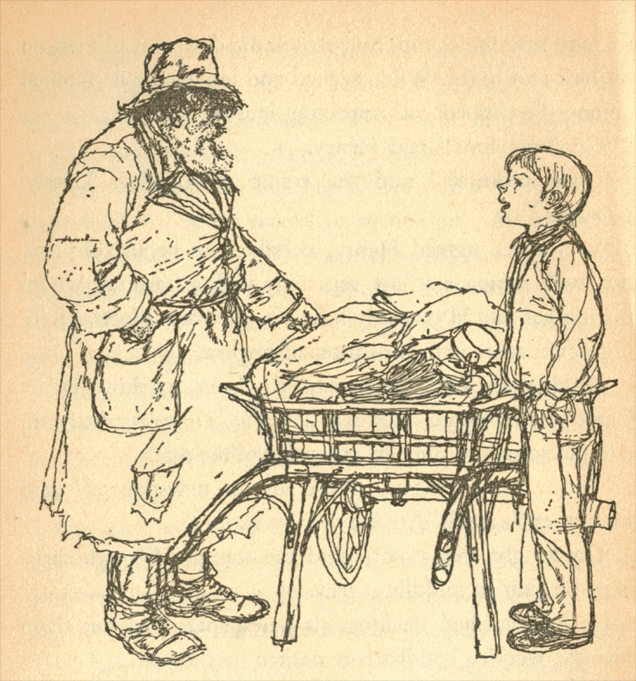

“Henry went right to the farthest side of the park, where narrow paths twisted among the shrubbery. He had given up hope. And then he rounded a sudden corner, looked up and saw the tramp. Sun struck the dew that glinted on his hair and beard. Wild, wicked and impossible he loomed among the clipped, self-respecting laurels”.

The films, TV and literature of the mid-20th century are riddled with eccentric, outsider figures… a barmy cavalcade of wacky professors building space rockets in sheds, of wild-haired suburban time travellers and reclusive, woodland-dwelling refugees from non-specific Ancient Times. But perhaps none feel quite so quaintly outdated as the simple, common-or-garden “tramp”. This is homelessness presented as romantic lifestyle choice: the round-shouldered, bearded drifter lugging a battered knapsack along sun-baked country lanes, sleeping in barns and repairing dry stone walls for soup. Long into the 1980s, the tramp was shunted amiably from sitcom to sketch show to children’s novel, with the occasional stopover into gentle TV drama, too… I recently watched an episode of All Creatures Great and Small in which Patrick Troughton (at this stage in his career, the go-to actor for eccentric outsiders of any type) played Roddy, an itinerant, rural rambler with a beard the size of Baldersby St James.

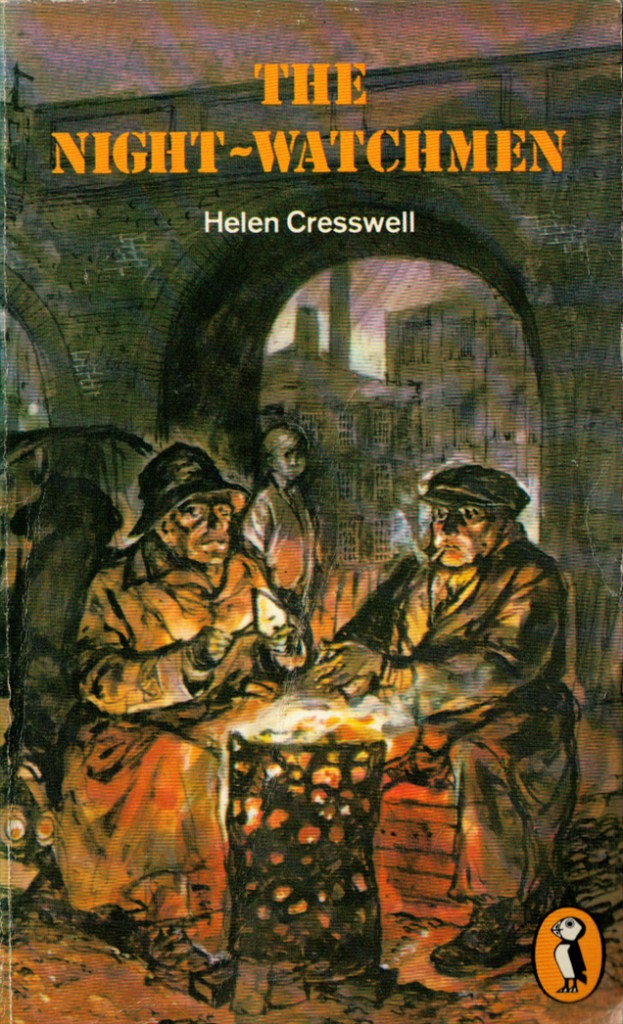

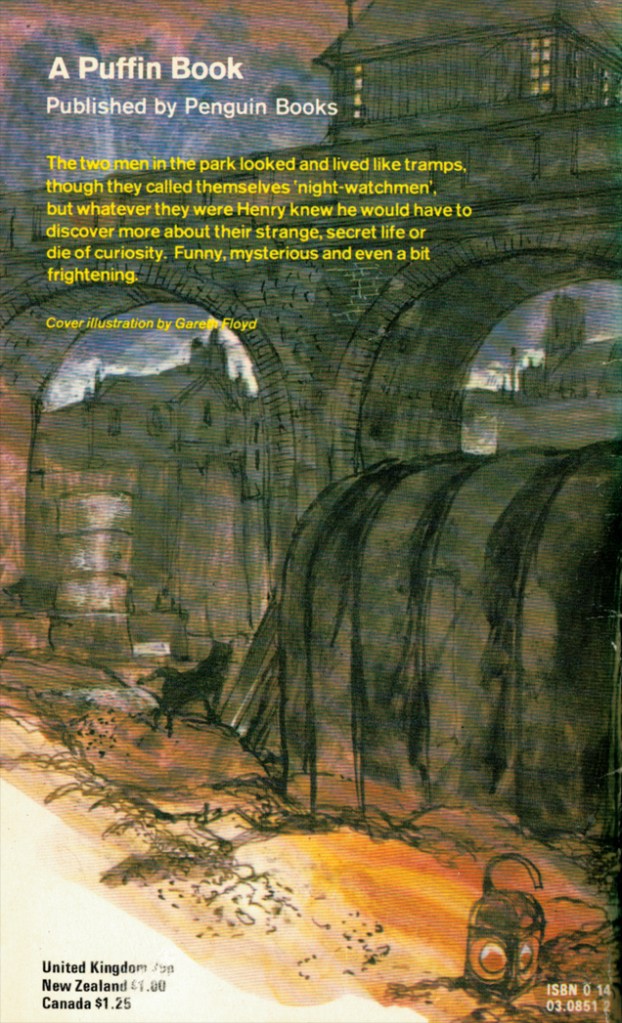

The idea of the tramp as a romantic figure, the mystical gatekeeper to a idyllic lifestyle of non-conformism (even James Herriott seemed wistfully envious of Roddy’s carefree pavement-pounding) is taken to fantastical extremes in The Night-Watchmen. Central character Henry is a terminally bored schoolboy suffering from some unspecified lurgy, bedbound for a month but – as the story begins – given license by his doctor to revel in that universal panacea for all feeble 1970s children: “fresh air”. Pottering around his local park at the crack of dawn, he chances upon Caleb and Joshua, two brothers sleeping rough amid piles of rolled-up newspapers. “Nothing like The Times for warmth,” shrugs Joshua, as Henry initiates a tentative conversation. We’re left to make our own guesses as to which daily publications are most suitable for morning toilet ablutions. I don’t need to think about it for long.

If the names seem vaguely familiar from long-ago RE lessons on damp February afternoons*, award yourself a gold star and a merit mark. In the Book of Numbers, Joshua and Caleb are two scouts dispatched by Moses to perform a recce on the Land of Canaan. Both return to confirm that their party has, indeed, found the Promised Land – an idyllic, permanent home for the nomadic Israelite tribes. In The Night-Watchmen, the Promised Land is the mysterious “There”, a similarly Elysian realm where the boring mundanity of “Here” (school, work, family life, Lulu singing ‘Boom Bang-A-Bang’) is forbidden to intrude. It is, we are told, the realm of the “Do-as-you-pleasers”. Joshua and Caleb, of course, hail from there “There”, and Henry – whose dreary lifetime trapped “Here” has been a study in stultifying ennui – becomes keen to experience at least a short holiday in this halcyon, don’t-give-a-toss idyll.

The method of transport between “Here” and “There” is easily the book’s most romantic conceit. One dark and magical evening, a mysterious, steam-driven “night train” will transport Joshua and Caleb back to the domain of the Do-as-you-pleasers. “She’s not on any timetables,” explains Caleb. Joshua elaborates: “She comes to our whistle the long and broad of England. She can weave her way through the junctions like a homing pigeon. Under the tunnels and over the moors, up dale and down river. Keeps the rails polished on the branch lines and can skirt a town with never a signal-box man to know”. Cobblers to Platform Nine and Three Quarters, eh?

While Joshua and Caleb wait for the perfect moment to summon this fantastical transport, they occupy themselves “Here” with acts of minor civil disobedience. Digging pointless holes at the roadside, for example, enables them to erect a workman’s tent for the night without attracting police attention. Caleb, we learn, is an accomplished chef (chicken and mushrooms followed by lemon meringue pie is declared by Henry to be “the best meal I’ve ever had in my whole life” – a shocking indictment of the late 1960s Findus range) and Joshua is forever writing a book about their travels, sporadically breaking cover to discuss this project with local schools and municipal bigwigs. Both brothers are masters of a curious, semi-mystical practice they call “ticking”… as Caleb explains, “It’s seeing and feeling. Both at the same time. Sniffing at a place, getting the scent of it. Sensing things”. And if this whole, dreamy lifestyle seems singularly pointless and wishy-washy to the modern eye, that’s entirely deliberate. Joshua and Caleb are keen to spell out their philosophy of life to Henry: life has no plan, and nor should it. “I wouldn’t rightly say that we do anything, It’s more a matter of what we are than what we do,” explains Joshua. And what are they? “We are Night-Watchmen”. Well, you did ask.

Which all begs the question – why are they wasting time digging holes “Here” when they could be living the life of riley “There”? Because, of course, there are dastardly agents of the mundane afoot. Sinister “Greeneyes” who despise the Do-as-you-pleasers and will come swarming if they hear the whistle of the night train, boarding it themselves to infect this freewheeling Arcadia with their own unique brand of dreary, routine misery. The Greeneyes are fabulously sinister figures, lurking in the murk: shadowy men whose eyes literally shine with jealousy. And their numbers, it seems, are massing.

It might not be the most subtle of metaphors, but it is incredibly creepy and affecting. Four years later, Helen Cresswell would bring Lizzie Dripping to British TV screens, with another otherworldly incursion (in this case, a cackling medieval witch) transforming the day-to-day dreariness of a lonely and uncertain youngster. The Night-Watchmen boasts a gentler, more understated brand of eeriness: “There”, for example, remains tantalisingly unseen and, at a push, the Greeneyes could simply be Henry’s fevered over-imagining of the hordes of deeply tedious men populating his home town. God help him if he ever joins Twitter. But the book shares a lot with Cresswell’s more famous creation, not least the idea that bored young people are dab hands at creating their own worlds of imagined weirdness, and that – frequently – these worlds become more real and enticing than the real thing. Has Henry met a couple of down-and-outs in his local park and simply dreamed up their ensuing adventures to enliven an existence of crushing, under-the-weather monotony? As with Lizzie Dripping, it’s impossible to tell – and the story is all the more affecting for it.

POINT OF ORDER: *My secondary school RE teacher, Mr Wilkinson, was from South Shields, and as a result my internal monologue automatically converts any Bibilical name, word or phrase into one of the strongest Geordie accents I’ve ever heard in my life. And God knows, there’s been some stiff competition. Mr Wilkinson’s speciality was an extraordinarily elaborate pronunciation of “The Pharisees”, which – on a good day – could easily push the syllable count into double figures.

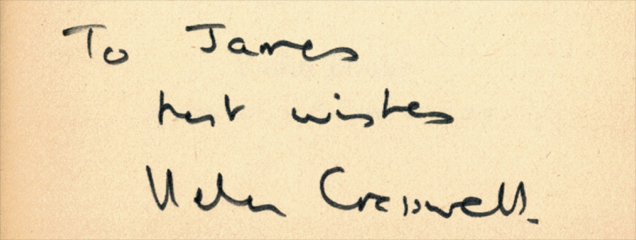

MUSTINESS REPORT: 8/10. My paperback copy runs the full gamut of creased cover, loose pages and paper the colour of a 1960s pub ceiling. But, after buying it for £2.20 in the Robin Hood’s Bay Bookshop in February 2023, I was delighted to discover it had also been signed (“To James”) by Helen Cresswell herself. Find your own copy, Greeneyes – this one’s mine.

Help support the Haunted Generation website with a Ko-fi donation… thanks!

https://ko-fi.com/hauntedgen

Love the artwork of the old style roadworks lamp in the bottom right-hand corner. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Cheers James – and yes, I’d forgotten all about those old lamps!

LikeLike