Don’t dwell in the past. It’s addictive and corrosive.

It’s perhaps ironic that such a sentiment should be the underlying moral message of a tale that has become such a totemic symbol of the 1980s childhood Christmas, due almost entirely to the superlative TV adaptation broadcast on BBC1 throughout November and December 1984. The transmission of the final episode, at 4.20pm on Christmas Eve that year, has ensured that the story’s conclusion – set amidst the echoing carols of the midnight service at Tatchester Cathedral – is now irrevocably linked to our generation’s heart-pounding anticipation of ZX Spectrums and Now That’s What I Call Music LPs, already wrapped and stockpiled in heavily-guarded parental wardrobes.

Nevertheless, Masefield’s message – conveyed far more forcefully in the book than the TV series – is unequivocal. Our collective concept of the past is idealised, even mythologised, and allowing it to intrude into modern life at the expense of the present (no matter how dreary the latter may seem) will inevitably lead to sickness and corruption. And possibly the kidnap of a Bishop, a small posse of curates and two football teams’ worth of grumbling choirboys.

The story: Plucky, well-to-do schoolboy Kay Harker is returning from boarding school to his family home Seekings, a rambling estate maintained by his youthful governess, Caroline Louisa, in lieu of his absent parents. While changing trains, he befriends an elderly Punch and Judy Man, Cole Hawlings, who ultimately agrees to perform a private Christmas show for Kay and his fellow Seekings residents: essentially, the four “Jones children”, whose parents have also considerately made themselves scarce for the festive period. Hawlings’ show arguably exceeds the remit of the average children’s entertainer (“The ceiling above them opened into a forest in a tropical night: they could see giant trees, with the stars in their boughs and fire-flies gleaming out”), and at its conclusion, with unexpectedly sinister carol-singers already at the door, he departs into a wall-mounted drawing of the Dents Du Midi mountain in Switzerland, bought to life with equally magical aplomb.

Later, amid the suitably dream-like qualities of a heavy snowfall, Kay feels inexplicably drawn to local beauty spot King Arthur’s Camp. Transported there at midnight by a talking pony waiting patiently outside the front door (“Mount and ride, Kay… for the wolves are running”) he finds many elements of that mythologised past already bleeding into the present day. The familiar, overgrown hill fortress of his childhood adventures has reverted to its Dark Ages heyday, replete with “broad, squat, shag-haired men and women” defending their livestock from a ferocious assault by said canines. The presence of Hawlings’ “Old Magic”, it seems, has created slips in time, and when the Punch and Judy man re-appears at the battle’s conclusion in the white robes of a wizard, he entrusts Kay with the possession of the titular Box of Delights, a small wooden container with – unlikely as this may sound – considerably more magical properties than the ZX Spectrum. Even the 48K model.

The box enables Kay to “go small” (reduced to Tom Thumb size), to “go swift” (magically flying above a perfect, snow-bound Herefordshire) or, when the lid is opened, to be immersed fully into that idealised Merrie England of a past. Acting as gatekeepers to this world are two elemental spirits, one of whom was virtually a household name in 1984. They are Herne the Hunter, the guardian of the “wild wood”; and the Lady of the Oak, whose magical realm of co-operative, nut-bearing squirrels and foxes exists entirely inside a hollow tree trunk known locally as the “She Oak”. Elsewhere, Kay encounters fairies (“The Very Good People” who “went away… a long time ago”, according to a helpful field-mouse) and a Roman legion encamped outside his bedroom window. These otherworldly experiences are described with affecting poetry, and frequently exist in the evocative hinterland between Kay’s wakefulness and sleep states, but even Herne and the Lady themselves warn of the dangers of succumbing to their temptations. “Did you see the wolves in the wood?” asks Herne, accompanying Kay on a shape-shifting flight through the Box’s fantastical foliage. “That was why I moved. Did you see the hawks in the air… and d’you see the pike in the weeds?” The message is clear: do not dwell among the temptations of fantasy. Keep moving forwards, or the dangers will become overwhelming.

The book has darker qualities than the TV series. The latter certainly glosses over the inclusion of Poppyhead, the ringworm-bound “dirty boy” who helms a gang of stone-throwing ruffians at the local docks, where cock-fighting and racehorse-nobbling are, apparently, rife. And perhaps more obvious in the book is the overriding reason for Kay’s predilection for dabbling with the fantastical: his 1930s existence is stultifyingly dull and repressive. He exists in a world of cold, privileged ennui where parental love is entirely absent, and the adults charged with his care are either professionally prissy (Caroline Louisa attempts to enforce a parental ban on slang: Kay, famously, hasn’t a “tosser to his kick”) or jaw-droppingly negligent.

The youngest Jones sister, Maria, vocally rebels against the dreary mores of the era, living in her own fantasy world of pulp novels and comics. “Christmas ought to be brought up to date,” she complains. “It ought to have gangsters and aeroplanes, and a lot of automatic pistols.” Her subsequent abduction by the villains of the piece – one of a spate of high-profile kidnappings – provides the perfect example of sluggardly adult indifference. Faced with the disappearance of a local child (and indeed, Cole Hawlings and Caroline Louisa, plus the local Bishop and the entirety of his staff and choir), the local Police Inspector steadfastly refuses to act, himself permanently lost in an idealised Victorian mind palace of bedtime possets and conjuring tricks.

And said villains? The powers of the box are craved by sneering jewel-thief and occultist Abner Brown – a character surely at least partly influenced by the high-profile 1930s antics of Aleister Crowley. Brown is holed up in a remote Ecclestiastical Training College in the distant woods of Hope-Under-Chesters, maintaining an unlikely alter-ego as the respectable “Rev. Boddledale” and surrounded by a motley coterie of modern-day “wolves”. Their number includes his femme fatale lover, Sylvia Daisy Pouncer; his dimwit henchmen Charles and Joe; and – endearingly – an anthropomorphic rat with a love of mouldy cheese and foul rum. Brown’s desire for the Box of Delights, and its power to transport him to the past, has already corrupted him beyond redemption. His abductees, taken in the erroneous belief that Hawlings has secreted the box at either Seekings or nearby Tatchester Cathedral, are kept imprisoned in a network of dungeons deep beneath the college. Where, despite the increasingly squeamish protestations of his underlings, Brown fully intends to drown them all by opening the sluice gates to the nearby river. It’s perhaps also worth acknowledging that a particularly unsavoury element of Brown’s character is his racism. Certainly in the unabridged version of the book that I read (See “Points of Order”, below) this is expressed in terms that will be unacceptable to many modern readers. It’s fleeting, and I don’t doubt the intentions of Masefield in ascribing such toxic views to the unhinged villain of his story, but it’s still hair-raising language that belongs very much in the 1930s.

A warning now, for those who have neither read the book nor seen the TV adaptation: Spoilers follow. Huge spoilers. Dirty great spoilers, concerning both the real identity of one of the book’s major characters, and the controversial final paragraph that entirely changes the context of everything that has preceded it. If this is likely to be an issue, look away now. Browse the rest of the Musty Books reviews, in which I’ve often gone to unnecessary lengths to keep the endings of 50-year-old children’s stories vague and unspoilt. Apart from The Weathermonger, but even then I gave ample warning.

But it’s really impossible to discuss The Box of Delights without revealing that…

Cole Hawlings is actually Ramon Lully, a Spanish alchemist from the 13th century who created an Elixir of Life and – on hearing of the existence of the Box of Delights – travelled to Italy to meet the medieval magician who created it. This was Arnold of Todi, who – we discover – has long since vanished into the fantastical past of the Box itself, becoming trapped there and leaving the magical object itself in the possession of the now-immortal Lully. Arnold’s plight reinforces Masefield’s point that disillusionment with the “now”, and the pursuit of escape into a mythologised past, are both timeless concepts and fruitless obsessions. In the book’s latter stages, Kay embarks on a quest to rescue Arnold, despite protestations from both Herne and the Lady of the Oak. “It is not always wise to take part with the Past,” warns the former, and both spirits are entirely aware of the dangers of the magical realms they inhabit. “It is a dangerous thing,” confirms Herne, even alerting Kay that his immersion in the trappings of centuries past will strip away an integral part of his identity. “The you that goes will cast no shadow,” he grumbles. “People won’t like that…” And when Arnold himself is discovered, exiled on a deserted Mediterranean island in the wake of the Trojan War, he is cracked and rambling, driven insane by his desire to escape “the dullness of the Time into which I was born” and by his bizarre, obsessive quest to befriend Alexander the Great.

One man’s medieval occultism is another man’s boring Christmas with the Joneses.

But perhaps the book’s most notorious aspect is its ending. And the unspoilered few that have recklessly kept reading really should look away at this point, because the book’s concluding paragraph reveals the entire story to have been an elaborate dream, no more than a product of Kay’s exhausted, post-school sleep on the long train journey back to Condicote. More than a handful of readers have understandably felt cheated by this denouement; not unreasonably peeved at having ploughed through 309 pages of poetic fantasy before having to accept the somewhat deflating conclusion that none of it actually happened. But I would attempt to offer consolation with three justifications:

Firstly, the clues are there. Much moreso than the streamlined TV adaptation, the book is fuelled by a sense of fractured logic and surrealism that only make sense in the context of a dream. There are scenes and locations that shift and bleed into one another, and the repeated, unquestioned imposition of impossible objects that seamlessly become part of an accepted dream reality. 1930s cars that metamorphose instantly into aeroplanes, then later re-appear in miniature flying form with the heads of wolves? Come on… as even the dull-witted Police Inspector tells Kay considerably earlier in proceedings: “The simple explanation is always the last one thought of”. Masefield must have been chuckling up his sleeve when he wrote that one.

Secondly, The Box of Delights is a sequel to Masefield’s 1927 book The Midnight Folk, in which Kay Harker has a similarly occult-tinged encounter with both Abner Brown and Sylvia Daisy Pouncer. While there is no suggestion that the events of this book exist merely in Kay’s subconscious, the glee with which Masefield incorporates elements of The Midnight Folk into Kay’s elaborate dream is a glorious mischief. My favourite example being that of the Jones children – Peter, Susan, Jemima and Maria – who exist in the previous work merely as lifeless dolls in Kay’s collection of toys. Reading both books in order of publication reveals much about both Masefield’s playfulness as a writer, and – indeed – his appreciation of the fecundity of the childhood imagination.

Thirdly, bugger it – “It was all a dream” probably felt more of a novelty in 1935. And nobody complains about The Wizard of Oz.

So the book is not flawless. Particularly, it’s adherence to fractured, dream logic makes for lengthy diversions that unsurprisingly refuse to conform to modern expectations of linear plot, but nevertheless add a surfeit of flavour. All composed in the mellifluous prose one might expect of a writer who – at the time of its publication – was Poet Laureate, and who would remain in the post until his death, 32 years later. “The carved beasts in the wood-work of the old houses seemed crouching against the weather. Darkness was already closing in. There was a kind of glare in the evil heaven. The wind moaned about the lanes. All the sky above the roofs was grim with menace, and the darkness of the afternoon gave a strangeness to the fire-light that glowed in many windows…”

Revel in its period charms, now so redolent of both 1935 and 1984. But – perhaps importantly – try not to dwell too long.

POINT OF ORDER: I waited a long time to find my copy, which is a 1977 reprint of the original Heinemann edition, and identical to the version of the book that I borrowed from my dusty school library in December 1984 after being entranced by the opening episodes of the TV adaptation. That memory is so vivid that finding the same edition of the book was really important to me. I know, I know. Addictive and corrosive.

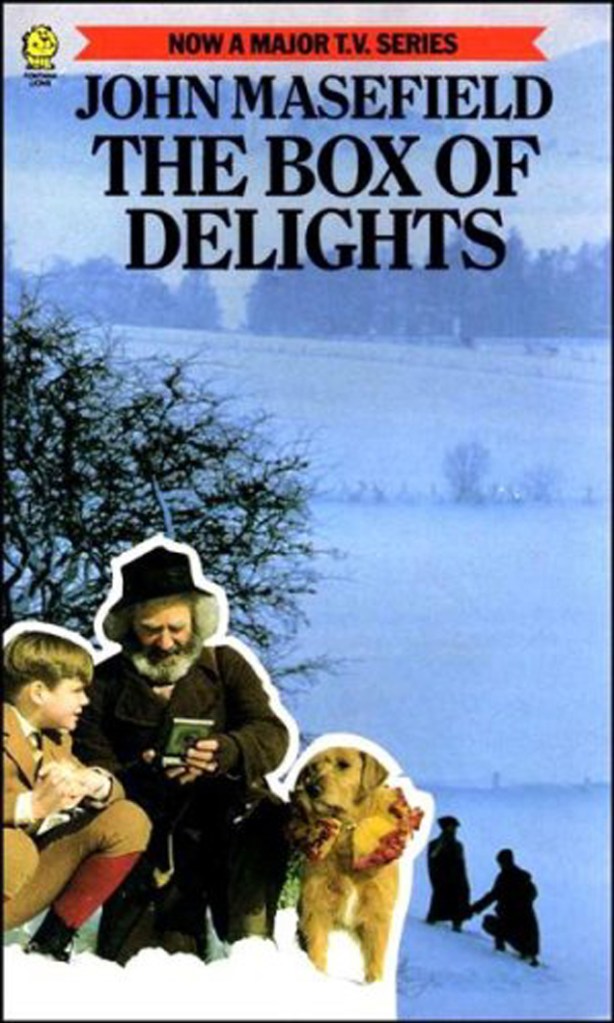

However, I’ve since discovered that the paperback version of the book published in 1984 (pictured above) to capitalise on the publicity of the TV series was substantially abridged – and I believe that this abridged text was used for several subsequent reissues. The full story is here:

Sound And Vision Special – November 1984

I’m still a little unsure as to how many versions of the book exist. Can anyone help, and I’ll happily post updates?

FURTHER POINT OF ORDER: The Hidden Britain Sign Company has recently begun producing a range of wonderful Box of Delights signage, all available here:

https://hiddenbritain.bigcartel.com/

The Condicote railway station sign is particularly impressive and I am fully intending to stick mine on my spare room door in time for Christmas, before I hole up in there playing card tricks with fake curates for the remainder of the festive period.

A new book, Opening The Box of Delights by Dr Philip W. Errington, is also now available:

http://www.dltbooks.co.uk/titles/2291-9780232534870-opening-the-box-of-delights

And with that, I hereby retire from my short-lived and unlikely career as an internet influencer.

MUSTINESS REPORT: 5/10. My copy of the book is in remarkably good condition for its age, although the first 26 pages have a intriguing crinkle in the bottom-right hand corner. I’m blaming bedtime posset spillage.

I loved Box of Delights when it came out in 1984 and it captivated me. It me until me mid 20s to read the book though, and will do so again (hopefully the unabridged version if I can work out which these are!). I’ve never read the other book, although have intended doing so, so will do that so can see those things I missed.

I watch the DVD most years. At the core is still a great story even if some special effects look mid-80s!

My big thing with it is, like many similar books, the way children are just left to do what they want. Four children are just left by their responsible adult for a few days!!! And when things go wrong Kay takes charge, and is more mature than the servants. Now this could be partly due to it being a dream, although how many other books are like this? I know with Agatha Christie book they always point out how servants and police are shown as dim as they are working class.

A couple of years ago some friends got married at Eastnor Castle, which was the Theological college in the TV version, and it was Christmas, so I was very excited taking a few photos of the key places from the scenes from TV.

LikeLike

Oh, that sounds fabulous! I must head over to that part of the world for a location visit at some point.

The most staggering aspect of the kids’ involvement in the story is Maria’s kidnap – nobody is particularly bothered, they just assume she’ll find her way out of it!

LikeLike

Great post! I have just finished my annual rewatch of The Box and it is as joyful as it was when, aged 6, I first saw it. I can’t find my copy of the TV tie-in so I have found another on eBay – interesting therefore to learn that the BBC version was abridged! I know that book so well that some of the lines are drummed into my head and I wince when I hear them in the script.

I haven’t read The Midnight Folk and am not sure if I want to as I am so fond of the Jones children. I’m also cross about the whole thing ending up as a dream – it really does feel like a cop-out. It still remains one of my all time favourites thouhg.

LikeLike

Oooh, now this is one I’m excited about! Never heard of it, and excited to look it out. Cheers, as ever

LikeLike

How lovely to know that there is a community of folk who also revelled in the Box of Delights. How I loved coming home from school and eagerly watching it. I even write to the BBC a long time ago to ask what the theme music was, and now Hely-Hutchinson’s Carol Symphony is one of my Christmas favourites. I have never been able to find an unabridged version, though i would love to have one.

LikeLike

Thanks Neia – I was the same as you, racing home in 1984!

LikeLike

Me three! People nowadays will never know the delicious anticipation of waiting for a programme week by week.

LikeLike

Hi Bob, great post. I was 12 when it came out (so come from Pagan times, in a manner of speaking) and the memory of the anticipation of those evenings in the run-up to Christmas are still very real. (I too had a Spectrum, and thought it vastly superior to the Commodore 64).

For the past 12 years or so, watching the DVD on subsequent evenings just before Christmas has become a family tradition, which we love.

By episode three, I begin talking in Abner Brownisms, to the chagrin of the rest of the family.

I read both books a while ago, and it wasn’t until I read that the Jones’s were toys that I began to think about it more deeply. Thank you for your summary and insight. Happy Christmas (You shall have your lights Your Grace) (Do come in, the service will go ahead).

LikeLiked by 1 person