The crackly, rustic theme tunes; the muted colour palettes; the crude but charming animated styles, the gently-clipped narrations by honey-voiced character actors, their fruity tones steeped in sugary tea and the pallid smoke of untipped cigarettes. The short cartoons of our 1970s childhoods – from Mr Benn to The Magic Ball, from Bod to Mary, Mungo and Midge – had a very distinctive style, and a very special place in our hearts; broadcast ‘for our younger viewers’ in the five-minute run-up to Pebble Mill at One, or sandwiched between Blue Peter and the unsettling headlines of the 5.40pm news. One final, daily hurrah of childhood innocence before Kenneth Kendall or Richard Whitmore arrived, and our cosy front rooms were once again subsumed by news of international arms races and imminent industrial action.

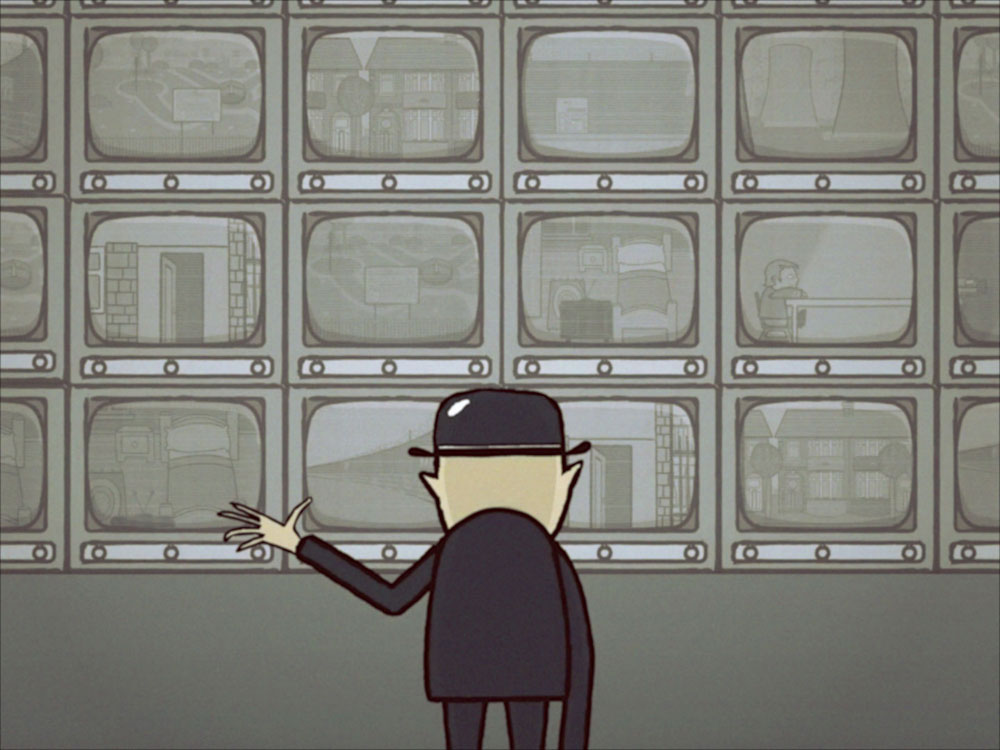

Richard Littler – who, since 2013, has been the benevolent overlord of Scarfolk, the dysfunctional North-Western town trapped in a perennial, authoritarian late 1970s nightmare – has combined many of these evocative factors to create Dick and Stewart. While re-creating perfectly the gentle trappings of those teatime institutions, it’s actually a nightmarish, satirical look at 21st century surveillance culture, seen through the eyes of a very 1970s schoolboy – the trusting, innocent Dick – and the living eyeball that he carries everywhere; the last, living remnant of his friend Stewart, who – we learn – has died in a playground accident.

Narrated by Julian Barratt, of The Mighty Boosh and Flowers fame, it’s a disturbing but beautifully-made piece of animation, with the pilot episode – I Spy With My Little Eye – available to watch, in full, on Youtube…

I asked Richard about the process of making Dick and Stewart, and the inspirations behind it…

Bob: Congratulations on Dick and Stewart… it’s wonderful. Can you tell us a bit about the process of getting it made, and how difficult that might have been?

Richard: Thanks a lot. I was flying blind a bit because, although I’ve worked in motion graphics before, I hadn’t done any kind of character or narrative-based animation. It took me a while to find my feet and develop my own process. I ended up creating Dick and Stewart with a mix of open source software and Adobe After Effects, which I don’t think is typically used for this kind of production. There weren’t any deadlines so I just took my time. On my own, it took months to complete.

As a graphic designer, had you always harboured ambitions to try your hand at animation?

In addition to Disney, Warner Bros and Tex Avery – which was my favourite – I was also brought up on Terry Gilliam’s Python animated inserts. It was seeing his rudimentary style that first made me think that animation may be possible even for someone like me. Gilliam didn’t need a studio of Disney animators, nor did he care about the kind of slick refinement you’d see in a film like Fantasia or Sleeping Beauty. He just did it all in his bedroom, even when he was making it for the BBC. Gonzo or punk animation. Low-budget, daytime kids’ animations were also similarly simplistic.

Yes, it’s clearly very much inspired by the 1970s animations that we all saw as children… the likes of Mr Benn and Mary, Mungo and Midge. Can you talk us through your memories of watching these, and other shows of the same ilk, and how they made you feel as a child? Which of them were your favourites?

I loved the cartoons you mention. I also liked The Magic Ball and anything by Smallfilms… Ivor the Engine, Bagpuss etc. Looking back at the cartoons before I started Dick and Stewart, I was surprised how technically crude – albeit charming – some of them are. You can frequently see pencil marks, rubbings out and felt-tip pen strokes. Rostrum cameras were also used extensively, so thirty seconds might go by and the audience would only see a zoom or pan of a static illustration.

This slower pace gave many of the animations a dreamlike quality, which I responded to. I wasn’t as much a fan of noisier cartoons like Roobarb – as much as I love Richard Briers – or American cartoons like the Hanna Barbera stuff. I also preferred hypnotic narrators such as Ray Brooks and Oliver Postgate, the co-owner of Smallfilms.

The trance-like quality was compounded for me because I was always off sick with colds, flu or fevers, which cast a surreal and sometimes dark shadow over the programmes. I still remember that, during one fever, the weird, unblinking eyes of the background characters in Mr Benn unsettled me.

Interesting that you mention dreamlike qualities, as we’ve spoken before about your childhood inability to distinguish between reality and the horrible nightmares you suffered from… does that remain a motivating factor in your work?

I don’t think it’s a conscious factor, but I have always preferred art, music and books with dreamlike, or rather unexpected or out-of-place elements and qualities, though my interpretation of whether something is dreamlike or not is probably subjective, rather than the intention of the artist in question.

People often talk of the 1970s as being a decade of bright, clashing colours, but my memories are of everything being rather washed out and pale. And the colours of Dick and Stewart really capture that… was the colour palette something you thought about carefully?

You’re right, 1970s cartoons were quite washed out. Or all our TVs were on the blink! The colours were very important, so I spent some time extracting colour palettes from programmes such as Mary, Mungo & Midge, The Magic Ball, Mr Benn, Bod and Joe. The latter of which I’d never seen before, but I liked the thick, black, rough lines and distinctive period colours.

(Curiously, I’d never heard of Joe either, but it was broadcast on BBC1 throughout the early 1970s, with the second series – from which this episode comes – being narrated by Colin Jeavons…)

The themes of surveillance and authoritarianism are terrifying… is this a reflection of how you feel about the 1970s, with its powerful state, or more how you feel about the present day?

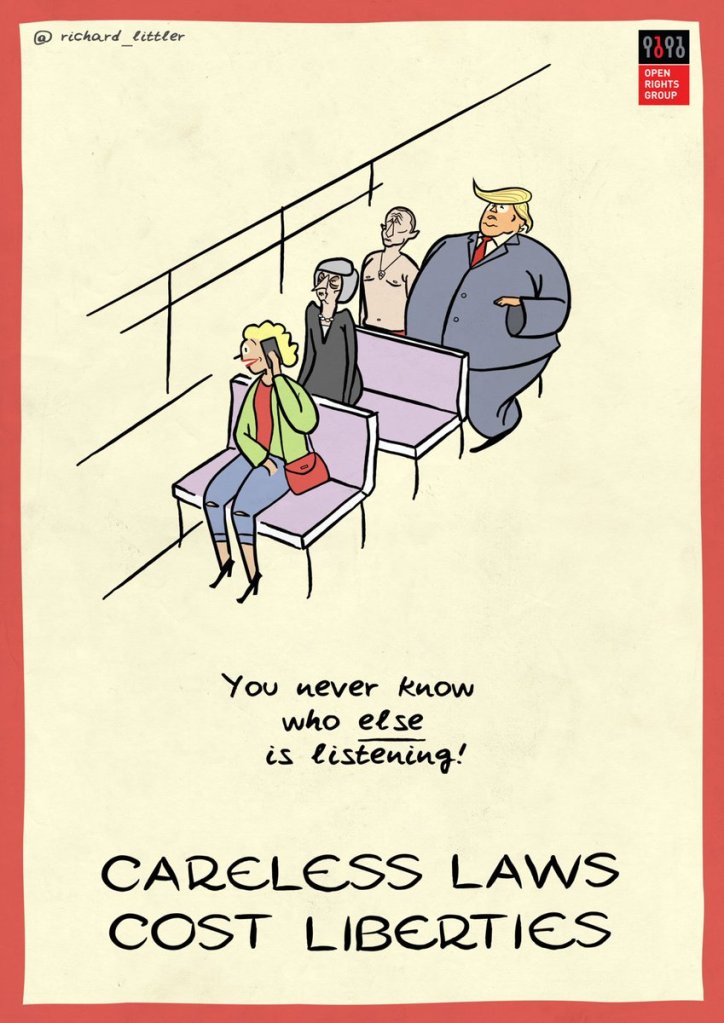

Although I loved the black-domed, in-store surveillance CCTV cameras in the 1970s, which resembled Dalek heads or the torture droid in Star Wars (I still want one!), the surveillance in Dick and Stewart is inspired by contemporary issues. Brits sometimes appear quite complacent about encroaching surveillance, more so than in other countries I’ve lived – Germany, for example. Last year, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the UK government’s bulk interception of data was against human rights. It’s an issue we need to… well, keep an eye on to ensure that civil liberties are not impinged upon, or worse. I’ve also completed similarly-themed design work for organisations such as the Open Rights Group. For example, a while back, I created a series of surveillance images parodying Fougasse’s wartime propaganda posters.

The normalisation of control is the most disturbing element of Dick and Stewart for me – as epitomised in the song, with its “watching is normal and healthy” refrain! Is this a road we’re being nudged down, do you think? Our everyday activities in 2019 are easier than ever to track and record…

We’re frequently at risk of signing away our privacy. I don’t think law has caught up with technological advancements yet, so there’s a constant tug of war between what is legal and what isn’t or shouldn’t be. Many companies (and the Government itself) sustain some of their activities via loopholes and/or with the hope that any wrongdoing hasn’t been detected, partially because it has not yet been clearly defined. Reality TV and phone cams have also normalised the idea of constantly being filmed and broadcast, and even that it’s desirable.

The idea of Stewart being the last remnant of a dead friend really struck a chord with me… my childhood seemed to be filled with rumours and urban myths of children that had died in terrible ways, and their stories were often presented as a lesson or a warning… ‘do you want to end up like that little boy?’ and all that. Was it the same for you? Any stories that have stuck in your mind?

Yes, the 1970s were full of well-meaning but horrific cautionary tales that involved the maiming or killing of children: Public Information Films about the dangers of pylons, railways, canals, farms, fireworks, electricity. When I was in infant school, rumours spread in the playground that a fellow pupil had suddenly vanished because he had been taken by a witch. At the same time, Public Information Films warned children not to go with strangers, so I took this as tacit confirmation that witches abducted kids from suburban playgrounds. The pupil hadn’t disappeared, by the way, his parents had moved house. Well, that’s what they say; I’m pretty sure it was witches. I hadn’t really thought about it until now, but it’s possible that Stewart came about because of the ubiquitous childhood warning, “Be careful or you’ll have your eye out with that!”

Julian Barratt’s narration is perfect… how did you get him on board? Was he someone that you always had in mind for this, and if so – what was it about his voice that made him so suitable?

I always knew that I wanted a soft “Ray Brooks type” narration, though for quite a while I was contemplating a female narrator. When I heard Julian’s narration, however, I knew that he was the perfect choice. He and Andy Starke, the producer, had worked together before, which made it easier. I’m very grateful that he did. I don’t recall that we discussed Ray Brooks specifically; I don’t think we needed to because Ray Brooks is such an icon in this field.

And needless to say, I love Chris Sharp‘s music… and he’s an artist that lots of readers will know from his work as Concretism. Do you go back a lomg way with Chris?

Chris was one of the first people to like Scarfolk so we’ve known other since then. I was an instant fan of his music and our respective creative projects come from the same well of early experiences. It captures the period perfectly and I’m so delighted that he let me loose on his album design. The Dick and Stewart soundtrack will be released soon, so people should look out for that.

This episode of Dick & Stewart is labelled as a ‘pilot’… are there further episodes in the works? What are your plans for it?

Five further episodes are already written and cover a range of contemporary topics including propaganda, civil defense, ‘fake news’, gaslighting and various forms of governmental corruption. Additionally, much of the artwork for the next two episodes is complete, but of course these things cost money and time and, ideally, the series would find a home on a platform other than YouTube.

Thanks to Richard for his time, as ever… and for providing the screengrabs in this feature. While we await further Dick & Stewart, it’s worth mentioning that Richard’s new Scarfolk Annual is released on 17th October, and is available for pre-order here…

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Scarfolk-Annual-Richard-Littler/dp/0008307016

Sinister stuff Bob. I’m enjoying these blogs.

LikeLike

Thanks! That’s very kind.

LikeLike

What talent you all have 🙏

LikeLike