“The most striking thing about the whole programme was the music. Until then, as far as I know, there hadn’t been any pure electronic music. In the early sixties there was still a fair amount of the old 1950s rock and roll around, but then this music came out… no instruments… purely electronic… and I’d never heard anything like it before…”

It was only a matter of time before my Uncle Trevor made an appearance in this blog. Trevor is a lovely bloke, and with the benefit of adult hindsight, I can see what a important influence his tastes exerted on my 1970s childhood. He liked electronic music. He liked Doctor Who. And the above quote is his abiding memory of watching the first episode of the show as a 10-year-old, in November 1963. Yes, he remembers William Hartnell emerging from the TARDIS in a murky Shoreditch scrapyard, but it was the whooshing, swooping, radiophonic theme music that truly captured his imagination. To the ten-year-old 1960s child, the experience of hearing music without any discernable instrument was… well, unearthly.

Although Doctor Who‘s theme had been written by Australian musician Ron Grainer, whose title music for Maigret, Steptoe and Son and That Was The Week That Was had already built him a solid reputation in the TV industry, it was arranged and realised by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Delia Derbyshire. Surrounded by piles of sliced analogue tape and test-tone oscillators, she painstakingly transformed Grainer’s notation into a resolutely avant-garde slice of musique concrète. Is it, alongside The Beatles’ Revolution #9, perhaps the most widely-heard piece of experimental music ever produced? Grainer himself was certainly taken aback. “Did I really write this?” he famously pondered, as Derbyshire played him the final mix. “Most of it,” she laconically replied. His subsequent noble attempts to secure her a co-writing credit were thwarted by grey-suited BBC beaurocrats, who preferred members of the Radiophonic Workshop to skulk in shadowy anonymity.

Nevertheless, Delia Derbyshire became a pivotal figure in the development of experimental, electronic music, firmly entrenched in that intoxicating middle-ground between art and technology, her life almost defined by the delicious power of contrasts: she was a working class Coventry girl who gained a scholarship to study mathematics at Cambridge University; a tweed-skirted former primary school teacher who found herself at the very farthest edge of the 1960s counter-culture. She exhibited music at The Million Volt Light and Sound Rave, the 1966 ‘happening’ at which The Beatles’ other experimental opus, the since resolutely-unheard Carnival Of Light, was aired. And – alongside fellow Radiophonic Workshop composer Brian Hodgson and US-born electronica enthusiast David Vorhaus – formed the band White Noise, whose 1969 album An Electric Storm is a captivating mix of psychedelia, occult-tinged folk-pop and eerie, disturbing soundscapes.

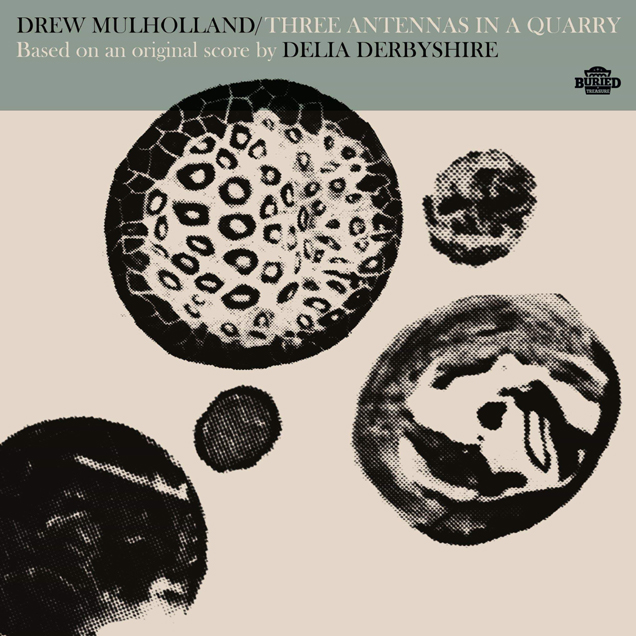

By the 1990s, Derbyshire had seemingly long-since stopped making music, however – towards the end of the decade – she befriended musicians Pete Kember and Drew Mulholland, collaborating with the former on a 2001 track entitled Sychrondipity Machine (Taken from an Unfinished Dream), and passing onto the latter the score for an unfinished piece of electronica, dating – as far as she remembered – from the late 1960s. I knew of Drew from his recordings as Mount Vernon Arts Lab, particularly his wonderfully atmospheric album The Séance at Hobs Lane, originally released in 2001, and then reiussed by Ghost Box Records in 2007. So I was intrigued to discover, earlier in 2019, that he had finally realised Delia Derbyshire’s “lost” score, transforming it into the album Three Antennas In A Quarry, now available from Buried Treasure records.

Drew’s interpretation is incredibly evocative of Deliba Derbyshire’s 1960s work for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and Doctor Who fans with a particular love of the William Hartnell era may find themselves drifting dreamily to a long-forgotten front room, or – indeed – to a gleaming corridor on a hostile alien planet. I might even buy a copy for my Uncle Trevor. I spoke to Drew Mulholland for my BBC Tees Evening Show, and this is how the conversation went…

Bob: I’m assuming that even before you got to know her personally, you admired Delia’s work a lot?

Drew: Yeah, even on my first records, on the run-out groove it said “Delia Derbyshire we salute you”! So she was always around. One of the things that I ‘fessed up to was that, when I was a 12-year-old, I did shoplift quite a bit… and one of the records I got was Out of This World by the Radiophonic Workshop. And I remember – because there were 100 tracks or something on it – writing down the ones that really stood out for me, and they were all by someone called “DD”. So I checked the index, and it was Delia, of course. And for me, as a 12-year-old, they were head and shoulders above everything else.

That is pretty esoteric music taste for a 12-year-old… like lots of us, did you come to the BBC Radiophonic Workshop through their work on Doctor Who?

Yeah, but also… I’m writing the story of how I got involved in music, and I had to – as Syd Barrett would have said – tread the backward path. So I was thinking about all of this, and it came from… not necessarily Doctor Who, but BBC Schools music. Those weird programme that we’d listen to, maybe on the World Service, that had all these sounds, rather than music. I think that sensibility was very quietly going on in the background, and I was soaking it up.

It’s odd, last week I watched Georgy Girl, the Lynn Redgrave film, and she’s a nursery school teacher, and in the opening five minutes she’s teaching kids to interpret what is clearly an experimental Radiophonic Workshop track! And you’re right, we did hear this stuff at school. Music, Movement and Mime…

That was one of them… I think that was a series of LPs. A lot of the stuff that Ghost Box have picked up on, that whole ethos, is very much based on that time. Now we’ve got so much distance from the 1970s, we can look back as adults and go “Actually, that was pretty weird…”. You know, the Public Information Films and all those hauntological tropes. It was a strange time.

It was a time when it wasn’t seen as particularly out of the ordinary to give really small kids some quite avant-garde things to listen to. It was seen as quite a healthy thing. I mean, the BBC produced this stuff for kids… the state broadcaster!

How times have changed!

So how did you get to know Delia? Did that happen in the 1990s?

Yeah, the late 1990s. It was Pete Kember from Spacemen 3, Spectrum and E.A.R… we were making a record together, and he phoned one day – very excited – and said “You’ll never guess who I’ve just been talking to…” and I said “Right, can you phone her back, and ask if it’s OK if this guy in Glasgow phones her?”

And I’ve told this story before, but I called her at seven o’clock, and she said “I’m really busy just now, can you call at twelve tomorrow?’ So right on twelve o’clock, I picked the receiver up and dialled the number… so her phone rang at about a minute past twelve. And she just picked the phone up and said “You’re late!'”

Ha! Rumour did have it that she was somewhat eccentric… and also quite reclusive by the 1990s. How did you find her as a person?

I’ll be diplomatic… it depended what time of day you spoke to her. If it was early on, she was sweetness and light and very helpful. She was great. Other times, not so.

I’ve seen you say that she was the only person you’ve ever encountered who could say “Oh Crumbs!” and not make it sound remotely contrived. Did she have that kind of sweet, old school quality to her?

Very much so. “Gosh and golly”, things like that! You didn’t even question it, it was just… that’s Delia. It was very natural, and hilarious of course.

So how did Three Antennas in a Quarry come into your posession? Was it something that you’d talked about working on together?

No, I think she was doing some recording with Pete Kember, it was around that time. We did a kind of mini-tour with E.A.R… Experimental Audio Research, one of Pete’s many groups. This would be summer or autumn 1998. And she’d phone up, and just say… without any pre-amble… “Do you use spices? I can get you some spices! My man works in a spice factory…”

And then she’d phone up and start talking about snuff…

Oh, I’d seen that she was a very enthusiastic snuff user…

Yeah! She said to me once that she’d had a special mix made up at the Sheffield snuff mills.

We need to find that, someone could market it… branded Delia Derbyshire Snuff. I suspect the market for snuff is quite niche these days, but you know…

One of the things that really annoys me is that Pete gave me one of Delia’s snuff tins… and I’ve lost it. I’ve no idea what happened to it.

If your house is anything like mine, it’ll be down the back of a radiator or sofa. So in what form did Three Antennas in a Quarry come to you? From listening to the album, it doesn’t sound like it lends itself to traditional notation.

No, not at all… it was a graphic score, which can be anything – a drawing, a sketch, dots on a page, a graph… it was very much the classic “scribble on the back of an envelope”. It was a sheet of A4, and there was a lot of numerical notation, and references to reel-to-reel tape recorders and what speed they would go at. So it was quite intense tying to find a route into it, because apart from the tape recorders and speed there wasn’t any direction as to how the music should go, the tempo, that kind of thing… but I like that, because I’m a researcher!

Where did some of the titles come from? ‘Calder Woodward’, for example?

A mixture of Calderwood, where I lived briefly as a child, and… Edward Woodward. You’ve got to have fun when you’re making a record!

Any idea what Delia had intended to do with the score? She even seems to have been quite vague about when she’d written it… the late 1960s, but she wasn’t quite sure…

No, she wasn’t sure. I don’t even know if it was supposed to be for the Radiophonic Workshop, or if it was a theatre piece… because she did lot of stuff for television and theatre… or if it was even an idea that she pursued. It was just one of those things that was either abandoned, or drastically transformed into something else.

Did you speculate at one point that she might have intended it for Syd Barrett, or Pink Floyd?

I don’t know… obviously it can never be proven, but I know that she invited Pink Floyd to the Radiophonic Workshop. We got the calendars out, and it would have been October 1967. And Syd was still in the band then, so the idea of Syd and Delia in the same room together fires the imagination.

She seemed to have this connection with the biggest rock stars of the day, and they had a fascination with her as well… didn’t Paul McCartney and John Lennon visit her at one point?

Yeah, Paul McCartney had written Yesterday, so this was 1965. And he knew that he didn’t want the full band to play it: he didn’t want the normal bass, two guitars and drums. So he asked George Martin -“What do I do with this?” and he said ‘”There’s this woman at the Radiophonic Workshop, go and have a word with her…”

I’d literally just read about that in Barry Miles biography of Paul McCartney, and I called her straight away, and said “What’s all this about?” And she now famously said “Yes, he came to see me… with the other one… the one with the glasses”. I said “That’ll be John Lennon, then?” She said “Lennon, that’s it… golly!”

So she lived in a separate world to the pop music of the era, then?

I think so, yeah. I visited Girton College in Cambridge [where Delia studied in the late 1950s] to give a talk there, and I did some field recording, and stayed there for a couple of days… and really started to get a sense of separateness. From the world, basically.

Although she did seem to have a certain fascination with Brian Jones from the Rolling Stones…

Yeah, we spoke to her up here for a radio interview, and she said that when she heard the news that he’d died, she was doing he washing up, and she cried into it. She said he was really nice, and remembered his frilly cuffs! But the spooky coincidence is that they both died on the same day… July 3rd. Which was also the day that my Dad died… and Jim Morrison!

Don’t throw any more in, it’s getting spooky! She’s such an extraordinary figure, and an ahead-of-her-time figure… my Uncle Trevor, who is a big influence on me, saw the first episode of Doctor Who broadcast in 1963, when he was ten… and he said it wasn’t so much the programme itself that stuck in his mind, it was the music… he and his friends had never heard music before where you couldn’t discern any particular instrument. That must have been a mind-blowing thing for an early 1960s kid. Incredibly forward-thinking.

Oh, incredibly! It’s like a stun grenade going into a room… there were only two channels on TV at that point, and not only did you have the introductory music, but you also had those visuals as well. The video feedback… it was the first time that had been used. And this wasn’t some out-of-the-way arts programme, it was teatime on a Saturday. I was two then, so I don’t remember it, but we’ve all grown up with the Doctor Who theme, and more and more television channels, and CGI and all this… but at that time, it must have been a bit of a cultural shift. Suddenly… this is what’s possible. And perfectly timed, in the early 1960s.

Yes, psychedelia, just before actual psychedelia…

Well that’s why they called it psyche-Delia!

Twenty years in regional radio, and I’m still being beaten to solid-gold opportunities for brilliant puns. “Pyschedelia Derbyshire”! Good grief, I hang my head in shame. Thanks to Drew Mulholland, and to Alan Gubby from Buried Treasure Records. A limited vinyl edition of Three Antennas in a Quarry has now sold out, but the full album can be downloaded here…

https://buriedtreasure.bandcamp.com/album/three-antennas-in-a-quarry

Hi Bob – excellent article once again, really enjoying these weekly posts & please keep it up! Along with the 50p Friday mails from Trunk, it’s something to look forward to at the end of the week. Thanks again, Eamonn.

LikeLike

Thanks Eamonn, that’s really kind. Glad you’re enjoying this!

LikeLike

I think the fact that she had a background in mathematics (and at Cambridge) is really quite important. I think there’s something about mathematicians, engineers and natural scientists (especially physicists, who you could argue are little more than applied mathematicians sometimes anyway) and electronic music that fit together.

I think the fascination with music as an intrinsically (and explicitly) mathematical thing goes back to JS Bach, and it’s no accident that Back was the place Wendy Carlos went to for her experiments. And experiments is exactly the right word, which kind of reinforces the point.

Lots of the early movers in things like musique concrète (Pierre Schaeffer was originally a radio engineer, for example, and the likes of Stockhausen, Boulez and Eloy had engineering connections to their music) had this rather technocratic education. I think perhaps it points up a certain midst – a love of order and pattern, an eye for form that is not merely aesthetic, but has a more formal expression. And in many cases, the access to, and confidence with, tools that allowed that to be realised.

Looking back from now, when it’s easy to produce sounds to fit a requirement, it’s hard to imagine the craft, patience and creativity need to be able to work with things like oscillators and layering tape loops, doing things like Roy Wood did later, bouncing overdubs form trac to track using tape machines. And of course, the relative narrowness of the palette helps to concentrate the mind no end: one looks for ever more creative ways to stretch this emerge resource and do something exciting and new.

LikeLike

(with apologies for typos)

Bach

mindset, not midst

meagre, not emerge

and a missing k from trac

Ironically, that last (truly inadvertent) missing k gives me the inevitable JMJ reference. Le Trac is the name of a painting by the French artist Michel Granger, who was responsible for the cover of Oxygene. This later painting, “stage fright” (Le Trac), was to become the iconic cover art for the album Equinoxe. And of course Jarre was a student of Schaeffer at the GRM in Paris, one of the hotbeds of MC. Jarre was actually more of an anomaly – not a mathematican, but a visual artist, but every exception proves the rule.

LikeLike

I do think a certain degree of restriction (of concept, or of format, or tools available) can be a very healthy aid to creativity. Would those early radophonic experiments have had the same otherworldly mystique if they’d been created with modern digital technology rather than tiny scraps of tape, sliced and re-stuck together? Possibly not.

The Beatles made Sgt Pepper in an four-track studio…

LikeLike

To quote that great philosopher, Zippy: Presactly

LikeLike